Desmond PDF

Preview Desmond

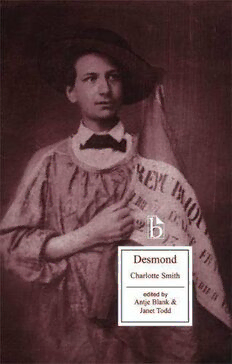

This electronic material is under copyright protection and is provided to a single recipient for review purposes only. DESMOND Charlotte Smith Review Copy Portrait engraved by Ridley and published in 1799 by Vernor & Hood. Review Copy DESMOND Charlotte Smith Edited by Antje Blank and Janet Todd broadview literary texts Review Copy ©2001 Antje Blank and Janet Todd All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without prior written consent of the publisher—or in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Cancopy (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency), One Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5—is an in- fringement of the copyright law. Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Smith, Charlotte, 1749-1806 Desmond (Broadview literary texts) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-55111-274-4 I. Blank, Antje, 1965- . II. Todd, Janet M., 1942- . III. Title. IV. Series. PR3688.S4D42001 823'.6 COO-932877-7 Broadview Press Ltd. is an independent, international publishing house, incorporated in 1985. North America: P.O. Box 1243, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada K9J 7H5 3576 California Road, Orchard Park, NY 14127 Tel: (705) 743-8990; Fax: (705) 743-8353 E-mail: [email protected] United Kingdom: Thomas Lyster Ltd. Unit 9, Ormskirk Industrial Park, Old Boundary Way, Burscough Road Ormskirk, Lancashire L39 2YW Tel: (01695) 575112; Fax: (01695) 570120 E-mail: [email protected] Australia: St. Clair Press, P.O. Box 287, Rozelle, NSW 2039 Tel: (02) 818-1942; Fax: (02) 418-1923 www. broadviewpress .com Broadview Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Book Publishing Industry Development Program, Ministry of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada. PRINTED IN CANADA Review Copy Contents Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 7 Charlotte Smith: A Brief Chronology 34 Works by Charlotte Smith 36 Further Reading 37 A Note on the Text 39 DESMOND Preface 45 Volume I 48 Volume II 159 Volume III 275 Notes 415 Appendix A. Extract from Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France 445 Appendix B. Extract from Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Men 449 Appendix C. Extract from Helen Maria Williams, Letters from France 452 Appendix D. Charlotte Smith, The Emigrants 455 Appendix E. Charlotte Smith, Letters to Joseph Cooper Walker and Joel Barlow 482 Review Copy Acknowledgements The editors would like to thank Judith Stanton for kindly making avail- able her edition of The Collected Letters of Charlotte Smith (Blooming- ton: Indiana University Press, 2002). They are also grateful to the John Rylands Library, Manchester, for a copy of the text of Desmond. Review Copy Introduction "Compelled to live only to write & write only to live"1 On 23 February 1765 Charlotte Turner, not quite sixteen, was mar- ried to Benjamin Smith, second son of Richard Smith, a wealthy Lon- don merchant with stock in the East India Company and sugar cane plantations on Barbados. Looking back nearly forty years later, Char- lotte Smith would refer to the event as a moment when ... my father & my Aunt (peace to their ashes!) thought it a prodigious stroke of domestic policy, to sell me like a Southdown sheep, to the West India shambles, not far from Smithfield (& they would have done me a greater kindness if they had shot me at once) ...2 This ill-advised marriage, "worse than African bondage," would determine the course of Charlotte Smiths future.3 Hastily contracted, it had been the means to rid the household of a young girl who squab- bled with her new stepmother, a 40-year-old woman whose large dowry had been a vital addition to her father's dwindling fortune. Charlotte was little prepared for life in a London merchant family. She had spent an affluent childhood at Bignor Park, the family estate on the picturesque Sussex Downs, and her early youth among fash- ionable London society; now she had to accustom herself to living in a gloomy second-storey flat in her father-in-law's house in Cheapside with relatives who she thought wanted refinement and education, frowned on her ignorance of housekeeping, and showed little under- standing of her fondness for reading, writing, and drawing. Her hus- 1 Charlotte Smith to Dr. Shirly, 22 August 1789. 2 Charlotte Smith to Lord Egremont, 4 February 1803. 3 Ibid. DESMOND 7 Review Copy band's character proved unstable; he was sometimes violent, frequently promiscuous, and habitually extravagant. Her father-in-law Richard Smith, however, took a great liking to Charlotte and recognized her literary talent, although he thought it would be put to best use in his counting-house. Charlotte declined becoming his paid clerk, but she continued to assist him in keeping the accounts until his death in 1776. Only too aware of his son's expensive habits, Richard Smith at- tempted to provide for Charlotte and her family by bequeathing the bulk of his estate to her children. By 1776 she had given birth to nine children; one had died in his infancy, another—her eldest son—would die the following year. Unfortunately, neither Charlotte nor her sur- viving children would ever benefit much from their inheritance of £36,000; Richard Smiths will, which tied up his property in a trust, had been written without legal advice. Complications soon arose and the trust became the subject of a prolonged legal dispute which was settled only forty years later.4 Legal proceedings first came to a head in 1783 when it emerged that Benjamin Smith, carelessly performing his duty as executor to the will, had run up high debts and diminished the value of the trust by more than a third. Other members of the family and beneficiaries of the will sued; as a result, trustees were appointed and Benjamin Smith found himself in King's Bench Prison. Charlotte chose to share much of the seven months' term with her husband. Harassed with debts, she decided to write for money, beginning with a series of sonnets. The renowned publisher Dodsley to whom she turned doubted their mar- ketability, but, encouraged by William Hayley, Smith published them at her own expense. Although she compiled her poems in the humili- ating environment of a debtors' prison, she ensured with her title that the public was aware of her claim to a more genteel station in life: Elegiac Sonnets, and Other Essays by Charlotte Smith of Bignor Park, Sussex (1784). The collection of sombre poems was immensely successful—in sev- eral ways. One immediate effect was, of course, financial, their profits contributing to Charlotte's and her husband s release from prison. In 4 For a detailed clarification of Richard Smiths will, see Florence Hilbish, Charlotte Smith, Poet and Novelist (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1941), 72- 81. 8 INTRODUCTION Review Copy the long term they established her reputation as a gentlewoman and author of serious verse and thus lent greater respectability to her later productions in a less prestigious but more lucrative genre—the novel. Within literary history, Smith's Elegiac Sonnets played a significant part in the revival of the sonnet form in the Romantic period. As they went through numerous subsequent editions, they swelled into a two-vol- ume set, inspiring later poets such as William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and John Keats, and established the form as a proper vehicle for the expression of plaintive sentiment. Although many of the Elegiac Sonnets were explicitly autobiographical in their setting and mood, the public was still left in the dark about the specific legal, eco- nomic, and emotional causes of the poet's misfortunes—so much so that the gallant reviewer of The Gentleman's Magazine could state his preference for an imaginary distress, claiming he would have read her "exquisite effusions" with "diminished pleasure," could he have "sup- posed her sorrows to be real."5 Charlotte Smith's miseries, however, were only too real. Prison did nothing towards reforming Benjamin Smith. Soon he was in debt again, and his violent outbreaks escalated. On 15 April 1787, after 22 years of marriage, Charlotte Smith finally left him. "Tho infidelity and with the most despicable objects," she explained, "had renderd my continu- ing to live with him extremely wretched long before his debts com- pelled him to leave England, I could have been contented to reside in the same house with him, had not his temper been so capricious and often so cruel that my life was not safe." Her sister noted that Smith made a futile appeal to one member of their family to make just terms of separation.7 William, Smith's eldest son, had found employment in the civil service in India, and her second son Nicholas was about to follow him, but her remaining three sons and four daughters depended solely on their mother for their support. And with none of her mar- riage settlements providing for a separation and no legal arrangement to secure her fortune or her future income Charlotte Smith was left at the mercy of her husband Benjamin. 5 The Gentleman's Magazine (April 1786), 333. 6 Charlotte Smith to Joseph Cooper Walker, 9 October 1793. 7 Catherine Dorset's biographical sketch "Charlotte Smith" in Sir Walter Scott, The Lives of the Novelists (London: Dent, 1810), 321. DESMOND 9