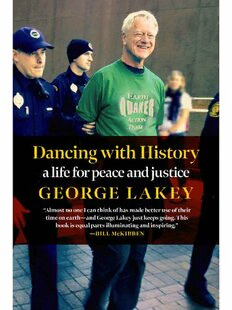

Dancing with History: A Life for Peace and Justice PDF

Preview Dancing with History: A Life for Peace and Justice

“George Lakey is a national treasure, whom I met when I was 22. Dancing with George was a blast. His unstoppable, thoughtful, contagious approach to democratic action has inspired my life’s work. It’s a story Americans need now more than ever.” —FRANCES MOORE LAPPÉ, author, Diet for a Small Planet, director, Small Planet Institute “George Lakey’s memoir is an epic of the personal in flow with the political—a dance with history indeed! As such, it is an outstanding example in the rich tradition of Quaker spiritual autobiography.” —DOUG GWYN, author of A Sustainable Life: Quaker Faith & Practice in the Renewal of Creation “Dancing with History packs a powerful, honest, and deeply personal account of George Lakey’s remarkable life and legacy of family building and movement building, honoring identity and liberation for all, ‘raising the temperature’ on what it means to live a life of social action and bearing witness. This book is a stunning testimonial, like walking through a historical landscape of a life of turning courageously to meet what’s next.” —VALERIE BROWN, writer, Buddhist-Quaker Dharma teacher, leadership coach, and facilitator “It is hard to express the depth of gratitude I have for the elders of social movements—people who have committed their lifetimes to cultivating the skills, frameworks, ideas, and ideologies that provide the foundation for activism today. George Lakey stands tall among these leaders. He will, I believe, go down as one of the great elders of the American radical democratic tradition. George is an expert in both building prefigurative community and planning strategic action. He is a master of pedagogy and a core resource for organizers thinking about how to train social movement participants. Countless grassroots leaders throughout the country are honored to claim him as a mentor. . . . His story is wonderfully presented in this autobiography.” —PAUL ENGLER, director, Center for the Working Poor in Los Angeles, co- founder, Momentum Training, co-author, This Is An Uprising. “George Lakey shows us how to ignite positive change in the face of adversity. He weaves in passion, creativity, faith, and even humor. An inspiring read for our moment.” —DAVE BLEAKNEY, education director for the Canadian Union of Postal Workers Copyright © 2022 by George Lakey All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Seven Stories Press 140 Watts Street New York, NY 10013 sevenstories.com College professors and high school and middle school teachers may order free examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles. Visit https://www.sevenstories.com/pg/resources- academics or email [email protected]. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Lakey, George, author. Title: Dancing with history : a life for peace and justice / by George Lakey. Other titles: Life for peace and justice Description: New York : Seven Stories Press, [2022] | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2022022539 | ISBN 9781644212356 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781644212363 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Lakey, George. | Pacifists--United States--Biography. | Nonviolence-- United States--History. | Peace movements--United States--History. | Social reformers-- United States--Biography. | Sociologists--United States--Biography. | Social change-- Study and teaching (Higher)--United States. | Civil rights workers--United States-- Biography. | Bisexual men--United States--Biography. | Quakers--United States-- Biography. Authors, American--20th century. | LCGFT: Biographies. Classification: LCC JZ5540.2.L35 A3 2022 | DDC 327.1/72092--dc23/eng/20220805 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022022539 Printed in the USA. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 contents Preface 1. A working-class lad finds a place to stand 2. Lessons in leadership 3. College offers breathing room and fresh challenges 4. Finding Quakers and a loving partner 5. I’m more activist than my college can handle 6. The only white student in the dorms of a Black college 7. Starting a family in a social democracy 8. North Philly and the Ivy League 9. Jailed in the civil rights movement 10. Violence greets opposition to the Vietnam War 11. My baby helps to save the trees 12. Community deepens the Vietnam movement 13. Threats and cheer on the home front 14. Piercing a naval blockade with medicine for Vietnam 15. Gunboats surround me in the South China Sea 16. Sharing strategy lessons in Britain 17. The tree of life, a book, and a new baby 18. Building the Movement for a New Society 19. A container for liberation 20. 1976 brings joy in the struggle 21. Getting the goods on cancer 22. Christina’s miracle 23. Campaigning for Jobs with Peace 24. Family stresses lead to major change 25. Confronting a homophobic Supreme Court 26. Training coal miners for a win 27. Responding to tragedy in Sri Lanka and at home 28. Putting training on the front burner 29. Wins for climate justice and democracy Photo Section Acknowledgments Index preface As I write this memoir, I see around me widespread anxiety about the state of the world. It is based in reality, but in my experience, anxiety itself isn’t very useful. Mahatma Gandhi once remarked that he didn’t try to “conquer” his fear because he needed its energy to stand up to the greatest empire the world had ever known. Gandhi learned to transform fear’s energy into the positive work of mobilizing for struggle. I’ve experienced that transformation many times in my own life, most dramatically in the civil rights movement, but also in struggles for peace, LGBTQ rights, labor rights, and the environment. I’ve included such stories in this book. I find there’s something deeply human about wanting to show up—to be, as Latin American activists might say, “presente!” One way I think of my life’s mission for peace, justice, and equality is to make it right for everyone to be present. Younger people often ask what keeps me going. I always point to the love I’ve found in friendship, family, teaching, faith, and community. Another part of my answer is that I’ve gained tremendous energy from investing in my learning curve: win, lose, or draw, I want to get better at this tough but bracing task of making a difference. I’ve wanted to learn from these seven decades of standing up for justice —from preaching racial equality at the pulpit of my church when I was twelve years old to being arrested for blocking the entrance of a Chase bank at age eighty-three, while participating in the 2021 Walk for Our Grandchildren in pursuit of climate justice.* As we sat in rocking chairs, demanding that Chase stop funding the fossil fuel industry, I was reminded of the struggle against South African apartheid decades earlier, when advocating for divestment was one of the winning tactics. I vividly remember pushing the City of Philadelphia to divest from the apartheid regime—as well as the joy that comes from going beyond awareness of injustice and toward acting for justice. Inspired by the protesters in South Africa, we turned a large protest in front of City Hall one frigid evening into an all-night dance, fueled by the beat of South African movement songs. I found that hour after hour of dancing with friends and strangers alike did more than keep us warm physically. It reminded us that if we tune in to what’s happening and act with others, we get to dance with history. * My account of the arrest, plus a photo, are here: George Lakey, “Arrested in Rocking Chairs, Grandparents Protest Chase and Pressure Biden on Climate,” Waging Nonviolence, July 3, 2021, https://wagingnonviolence.org/2021/07/grandparents-walk-biden-chase-climate/. 1 a working-class lad finds a place to stand I was born in 1937, a year when Michigan autoworkers waged a major sit- down strike and broke through the resistance to unionization by auto giant General Motors.* That decade was a period of turbulence for workers, Black people, women, professionals, and young people. As the Great Depression lagged on, many were questioning a social order that had betrayed its potential for justice, equality, and peace—and they were acting out those questions. I was the second child of three; my big sister, Shirley, was already four when I was born. My family lived in Bangor, Pennsylvania, a small slate- mining town surrounded by farms, midway between Scranton and Philadelphia. My dad, Russell, knew he had to hustle with an additional mouth to feed now, but there was nothing new about that. As a young teenager, his grandfather had come to Pennsylvania from Cornwall, in the United Kingdom, as an indentured worker for the slate mines. The Cornish were famous for their affinity for digging in the earth, be it for coal, copper, or slate. The family story was that this ancestor worked for years to pay off his passage to the United States, then more years to be able to send for his sweetheart to come and join him. Compared with that, my dad figured he had it pretty good. As a slate miner, he’d accepted that he’d worry about money all his life, and he did. The street I grew up on was typical of my town: a block of duplex houses with front porches. Summer evenings usually found the older generation sitting on rocking chairs on the porch, telling stories—often funny, sometimes poignant—while we “young uns” listened and a neighbor or two leaned on the front banister. I can’t remember a family occasion that wasn’t full of stories. I got it: life is about stories, which have a beginning, middle,