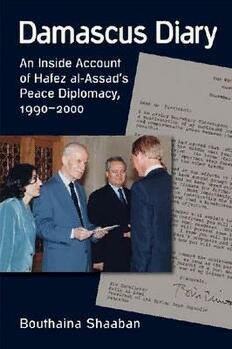

Damascus Diary: An Inside Account of Hafez Al-Assad’s Peace Diplomacy, 1990–2000 PDF

Preview Damascus Diary: An Inside Account of Hafez Al-Assad’s Peace Diplomacy, 1990–2000

Damascus Diary Damascus Diary An Inside Account of Hafez al-Assad’s Peace Diplomacy, 1990–2000 Bouthaina Shaaban boulder london Published in the United States of America in 2013 by Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc. 1800 30th Street, Boulder, Colorado 80301 www.rienner.com and in the United Kingdom by Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc. 3 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, London WC2E 8LU © 2013 by Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shaaban, Bouthaina. Damascus diary : an inside account of Hafez al-Assad’s peace diplomacy, 1990–2000 / Bouthaina Shaaban. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58826-863-1 (alk. paper) 1. Syria—Politics and government—1971–2000. 2. Assad, Hafez, 1930–2000. 3. Middle East—Politics and government. I. Title. DS98.4.S53 2013 956.05'3—dc23 2012025115 British Cataloguing in Publication Data A Cataloguing in Publication record for this book is available from the British Library. Printed and bound in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992. 5 4 3 2 1 To my late parents, Mr. Younis Shaaban and Mrs. Abla Al Ali, who taught me how to love, forgive, and work for peace Contents Foreword, Fred H. Lawson ix Acknowledgments xiii Introduction 1 1 The Road to Madrid 9 2 Blessed Are the Peacemakers 39 3 The Rise of Bill Clinton 61 4 Syria’s Honeymoon with Clinton’s America 79 5 The Deposit That Never Was 95 6 Rabin’s Assassination and the Long Road to Nowhere 117 7 The Legacy of Yusuf al-Azma 129 8 The April Understanding 137 9 The Not-So-Secret Lauder Talks 157 10 The Shepherdstown Debacle 171 11 The Man Who Did Not Sign 187 Epilogue 199 vii viii CONTENTS Appendixes 1: Letter from George H. W. Bush to Hafez al-Assad, May 31, 1991 203 2: Letter from Bill Clinton to Hafez al-Assad, May 27, 1993 207 3: Letter from Bill Clinton to Hafez al-Assad, July 4, 1993 211 4: Letter from Bill Clinton to Hafez al-Assad, September 4, 1993 213 5: Letter from Bill Clinton to Hafez al-Assad, December 2, 1993 215 6: Letter from Bill Clinton to Hafez al-Assad, October 12, 1999 217 7: Minutes of the Telephone Conversation Between Bill Clinton and Hafez al-Assad, January 18, 2000 219 Chronology of Key Events 223 Cast of Characters 229 Bibliography 231 Index 235 About the Book 245 Foreword Fred H. Lawson HOW SYRIAN FOREIGN POLICY ACTUALLY GETS MADE REMAINS largely unknown. Scholars and journalists alike assume that since the coun- try’s last coup d’état in November 1970 the president has dominated the policymaking process, if not drawn up and conducted foreign affairs all by himself. Even observers who enjoy close personal relations with Syria’s successive leaders imply that no real discussion or bargaining takes place among members of the political elite about matters of diplomacy and na- tional security. But we are not really sure, because insider accounts of pol- icymaking in Damascus have been nonexistent, in any language. Into this void comes Bouthaina Shaaban’s memoir of her years as per- sonal interpreter and external relations adviser to Hafez al-Assad, who was president of Syria from March 1971 until his death in June 2000. Shaaban’s story is primarily the improbable tale of an ambitious, energetic, even star- struck high school graduate from an obscure village who brings herself to the attention of the country’s new leader during his first visit to the military acad- emy in Homs. Remarkably, the president takes note of the bold young woman and promises to assist her in pursuing a university education. Her father, not sure what to make of his daughter’s brashness and extremely suspicious that anything will come of her endeavor, stays home when she is abruptly sum- moned to the Presidential Palace for an audience. Thanks to her audacity, the regulations that govern financial assistance to university applicants from poor backgrounds are immediately amended; she enters the English literature pro- gram at Damascus University and leaves her home ground far behind. As personal interpreter to President Hafez al-Assad, Shaaban finds her- self involved in a succession of closed-door meetings, sometimes with only her patron and a US president, secretary of state, or special envoy in the room ix x FOREWORD alongside her. Her accounts of such encounters must therefore be considered authoritative, and she on occasion explicitly contrasts her own recollections with those that have been recorded by US officials. It does not matter so much which version turns out to be true; the divergent reports underscore significant differences of perception and interpretation as much as they do disagreements over facts. Shaaban’s narrative is no more or less colored by political interest or concern for the writer’s historical legacy than are the pub- lic memoirs that have been composed by the United States. In addition to her own memory, Shaaban relies on unpublished min- utes, letters, and background papers culled from the archives of the Syrian presidency and the Foreign Ministry in Damascus. Such documents have never before been exploited, and they provide assessments of events and personalities that constitute a truly Syrian perspective on international af- fairs. Again, whether the viewpoint is right or wrong, or better or worse than that of the US Department of State, is beside the point. Much more than any analysis that might be constructed by outside scholars and diplo- mats, no matter how learned and astute, Shaaban’s memoir really does con- stitute a view from Damascus.1 And what does it show? First, it hints that there is indeed some sort of process behind foreign policymaking in Syria. In May 1994, US secretary of state Warren Christopher arrived in Damascus, carrying a provisional offer from Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin to withdraw from the Golan and dismantle Israeli settlements over a period of five years. President al- Assad told Christopher that he would give an answer the following day, and during the next twenty-four hours he sat down with three senior figures— Foreign Minister Faruq al-Shar’, Minister of Defense Mustafa Tlas, and Chief of the General Staff Hikmat Shihabi—to work out a suitable response. Shaaban notes that the Syrian president, “contrary to what the Americans thought, was a very consensual leader who was very careful to consult with his top officials before reaching a strategic decision of such magnitude.” One wishes that other examples of high-level policymaking had been in- corporated into the text, and that they spelled out the alternatives that got ad- vanced, weighed, and rejected during the course of deliberations. Second, Shaaban’s account belies the usual notion that Hafez al-Assad was a stone-faced, “taciturn” statesperson.2 The posters that cluttered the walls of Damascus throughout the 1990s, which often displayed a broadly beaming president, turn out to be right: the Eternal Leader possessed a keen sense of humor. When Secretary of State James Baker remarked that Dam- ascus’s announcement that Syria was going to attend the 1991 Madrid con- ference had shifted the spotlight away from Mikhail Gorbachev’s triumphant arrival at the summit of the Group of 7 industrial states, al-Assad adroitly responded, “We actually did that on purpose to create some prob-