Table Of Content10) 50 FCNOG O)H.) C0)2

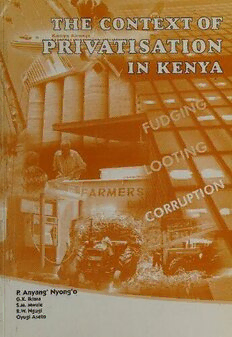

PRIVATISATION

IN KENYA

P. Anyang’ Nyong’o

G.K. Ikiara

CONTEXT OF

PRIVATIZATION

IN

KENYA

P. Anyang’ Nyong’o

G. K. Ikiara

S. M. Mwale

R. W. Ngugi

Oyugi Aseto

Citation: African Academy of Sciences (AAS), 2000

Context of Privatization in Kenya

© 2000 AFRICAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

P.O. Box 14798

Nairobi, Kenya

Published by Academy Science Publishers.

P. O. Box 24916

Nairobi, Kenya, E-mail <[email protected]>

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying,

recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Publisher.

First printing 2000.

The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this study are entirely those of

the authors and should not be attributed in any manner to the African Academy of

Sciences, to its Fellows or to members of its Governing Council or to the countries they

represent.

Printed by

Colourprint Ltd

P.O. Box 44466

Nairobi, Kenya

ISBN 9966 - 24 - 055 - 1

Contents

Acknowledgements

Preface Vil

jis Privatization: Conceptual Issues

P. ANYANG’ NYONG’O

Privatization in Africa: the Kenyan Experience

in a Comparative Perspective 18

P. ANYANG’ NYONG’O

A Review of Kenya's Public Sector of)

GERRISHON K. IKIARA

Genesis and Evolution of Privatization

Policy in Kenya ao

SAM M. MWALE

Techniques, Methods and Procedures

of Privatization 83

ROSE W. NGUGI

Issues and Problems in the Implementation 11]

of Privatization

Pp. ANYANG’ NYONG’O

Capital Markets and Privatization in Kenya 143

OYUGI ASETO

172

Contributors

ill

Appendix 181

Acknowledgements

| WOULD LIKE TO ACKNOWLEDGE the financial support given by the United States

Aid for International Development (USAID) for the research, seminars and

workshops which led to the publication of this book. The research is still continuing

and we hope to publish a second volume focusing on the privatization of strategic

parastatals as well as the general impact of privatization on the Kenyan economy

and society.

The research team comprising Rose Ngugi, Sam Mwale, Oyugi Aseto, G.K.

Ikiara and I, would like to thank all those who have attended our workshops and

seminars and made invaluable comments on our research results and analyses.

I would like to mention here the inspiring words of Kabage Karanja when he

opened our March 1999 seminar and challenged us to pay attention to experiences

in other societies within the context of comparative cultures. Special thanks to

Andrew Mullei and Crispin Bokea of International Center for Economic Growth for

the detailed comments on the original proposal as well as earlier drafts of these

papers.

Special thanks to Shem Ocholla who was always thorough and punctual in

compiling reports of the workshops and seminars. Without his keen attention, the

editing of this book would not have been as easy.

Special thanks to Emmy Mwavua, my personal assistant, for competently

managing the financial affairs of the project, and the African Academy of Sciences

which has been a wonderful host. Margaret Anaminyi did the technical editing

and typeset the book in record time.

Finally, special thanks to my wife, Dorothy Nyong’o, and my family for enduring

my long hours of absence from them. I hope this will be rewarded the day our

nation will be better governed and we will have leisure time to spend together.

Prof. P. Anyang’ Nyong’o

siakw 2 Z -

oe ORAM. a 7s sage 7}

Bice eso tn sik lg ala lbs ve,r

a seaalane oie phe’

has sone wo bulppine:v en 4

aazvtian bowi er herein al fe ceirli

v tre n ait vt

SHORRDO FTe liEe inN. ane ine

ob allavett goa aeuiph ‘

“Ne ihwerD- (erv cab beats,”

wi nedioheiae pane en

al a a 6 »

) i i a ae

(raeqmnn bat eanitge een Pt tid iit

st fo dita praia ely

aritibe lésin: ato“ ote al* dba

arta WA atin uh hatarartt

wt Veb oa) bobvapny =) fen.

dort yn hese of sdeert a

Preface

WHEN I WAS CHAIRMAN OF THE PUBLIC INVESTMENTS COMMITTEE of the National

Assembly during the Seventh Parliament in Kenya (1993-97), I noticed that Kenya

had embarked on a half-hearted process of privatization that few people understood,

let alone appreciated. There was no proper legal framework nor were proper

institutions set up to undertake a task that would profoundly affect the political

economy of Kenya.

The issue of privatizing the Milling Corporation of Kenya was reported to our

Committee by the Auditor General (Corporations) after he had undertaken a special

audit revealing that there had been gross irregularities and under-valuation of the

firm. Although we recommended that the so-called privatization be cancelled and

fresh bidders be invited, the government took no action. In the meantime, many

Kenyans were complaining about the looting of public assets by well-connected

politicians and government officials. This was usually done in the name of

privatization, or rolling back the role of the government in the economy.

Much more dramatic was the case of workers being laid off as public enterprises

started to downsize. This, apparently, had been a recommendation to the

government in a Policy Framework Paper worked out with the World Bank

encompassing civil service reform as part and parcel of a major reform initiative.

We were disturbed that discussions on reform were being carried out secretly

between the government and the Bretton Woods Institutions while they were of

Vil

major importance to Kenyans. It was proposed in the Policy Framework Paper of

1993-96 that privatization would more or less be complete by 1997. We started to

wonder how this could be achieved if Kenya did not, in the first place, have proper

institutions for privatizing even a small firm like Milling Corporation of Kenya. Or

was the lack of preparedness an excuse for offloading public assets to the power

elite at throwaway prices under the guise of privatization?

During Parliament’s recess in early 1996, I spent a month at El Colegio de

Mexico and started to read extensively on the subject of privatization, particularly

in transition economies (former Soviet Bloc countries) as well as developing

countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. It soon became clear to me that while

privatization was a necessary part of economic reforms needed in these countries

to generate social progress, the manner in which it is carried out could easily lead

to entrenching powerful oligarchies in society that could, at the same time, be anti-

democratic.

The ruling elites in these societies, having enjoyed tremendous economic

privileges where one-party regimes were predominant, may easily use privatization

to transfer monopoly from the public to the private sector. The same inefficiency

that characterized public enterprises could then resurface in privatized firms. With

little interest in entrepreneurship but a large appetite for looting public assets, this

elite would soon sell the assets so acquired and move their wealth elsewhere,

thereby undermining capital formation in the economy.

On the other hand, were privatization to be undertaken in a context where the

rules of the game are clear and institutions which encourage competition in the

buying of public assets well set up and known, it would perhaps not be used as a

tool for enriching the power elite. Further, where accountability for the proceeds

realized is protected by law, privatization would contribute positively to the treasury

and most likely help in kick starting the economy.

Investors are usually more willing to invest in impersonal markets where property

rights are more protected, contracts are less costly to enforce and government

policies are relatively credible. Property rights will be protected, contracts enforced

and government credible when laws are in place to register and enforce rights and

obligations; when constitutional, legislative and electoral rules make it hard to

change laws arbitrarily, and when legal and bureaucratic systems function

effectively, efficiently and honestly.

Vill