Component costs of foodborne illness: a scoping review PDF

Preview Component costs of foodborne illness: a scoping review

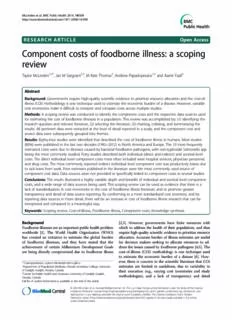

McLindenetal.BMCPublicHealth2014,14:509 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/509 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Component costs of foodborne illness: a scoping review Taylor McLinden1,2*, Jan M Sargeant1,2, M Kate Thomas3, Andrew Papadopoulos1,2 and Aamir Fazil4 Abstract Background: Governments require high-quality scientific evidence to prioritize resource allocation and the cost-of- illness (COI) methodology is one technique used to estimate the economic burden ofa disease.However, variable costinventories make it difficult to interpret and compare costs across multiple studies. Methods: A scoping review was conductedto identifythecomponent costs and the respective data sources used for estimating the costof foodborne illnesses ina population.This review was accomplished by: (1) identifying the research questionand relevant literature, (2) selecting the literature, (3) charting, collating,and summarizing the results. Allpertinent data were extracted atthe level ofdetail reported ina study, and thecomponent costand source data were subsequently grouped into themes. Results: Eighty-four studies were identified thatdescribed thecost of foodborne illness inhumans.Most studies (80%)were publishedin thelast two decades (1992–2012) inNorth America and Europe. The 10 most frequently estimated costs were due to illnesses caused bybacterialfoodborne pathogens, with non-typhoidal Salmonella spp. being the most commonly studied. Fortystudies described both individual (direct and indirect) and societallevel costs. The direct individual levelcomponent costs most often included were hospital services, physician personnel, and drug costs. The most commonly reported indirectindividual level component cost was productivity losses due to sick leave from work. Prior estimatespublishedin theliterature were the most commonly used source of component cost data. Data sources were not provided or specifically linked to component costs in several studies. Conclusions: The results illustrateda highly variable depthand breadth of individualand societal levelcomponent costs, and a widerange of data sources being used. Thisscoping review can be used as evidence that thereis a lack of standardization incost inventories in thecost of foodborne illness literature, and to promote greater transparency and detail of data source reporting. By conforming to a more standardized cost inventory, and by reporting data sources inmore detail, there will be an increase incost of foodborne illness research that can be interpreted and comparedin a meaningful way. Keywords: Scoping review, Cost-of-illness, Foodborne illness, Component costs, Knowledge synthesis Background [2,3]. However, governments have finite resources with Foodborneillnessesareanimportantpublichealthproblem which to address the health of their populations, and thus worldwide [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) requirehigh-qualityscientificevidencetoprioritizeresource has created an initiative to estimate the global burden allocation. Accurate burden of illness estimates are useful of foodborne illnesses, and they have stated that the for decision makers seeking to allocate resources to ad- achievement of certain Millennium Development Goals dresstheissuescausedbyfoodbornepathogens[4,5].The are being directly compromised due to foodborne illness cost-of-illness (COI) methodology is one technique used to estimate the economic burden of a disease [6]. How- ever, there is concern in the scientific literature that COI *Correspondence:[email protected] 1DepartmentofPopulationMedicine,OntarioVeterinaryCollege,University estimates are limited in usefulness, due to variability in ofGuelph,Guelph,Ontario,Canada their execution (e.g., varying cost inventories and study 2CentreforPublicHealthandZoonoses,UniversityofGuelph,Guelph, methodologies), and a lack of transparency and detail Ontario,Canada Fulllistofauthorinformationisavailableattheendofthearticle ©2014McLindenetal.;licenseeBioMedCentralLtd.ThisisanOpenAccessarticledistributedunderthetermsoftheCreative CommonsAttributionLicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0),whichpermitsunrestricteduse,distribution,and reproductioninanymedium,providedtheoriginalworkisproperlycredited.TheCreativeCommonsPublicDomain Dedicationwaiver(http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/)appliestothedatamadeavailableinthisarticle, unlessotherwisestated. McLindenetal.BMCPublicHealth2014,14:509 Page2of12 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/509 when describing such methodologies. Of particular con- costs in those categories to include (e.g., treatment costs, cernarethedifferingcostinventoriesbeingusedwhenes- productivity losses, industry costs), and the level of detail timatingthecostoffoodborneillnesses[7-10]. by which costs should be estimated (e.g., which types of The COI approach traces the flow of resources associ- treatment or industry costs to include). It is also challen- ated with adverse health outcomes through the quantifi- gingtointerpretorcompareestimateswithoutfullyunder- cation of measurable individual and societal level costs standingwhichcomponentcostswereincludedinastudy. [7,11,12]. Costs at the individual level are divided into Anotherconcernisthelackoftransparencywhendescrib- directandindirectcosts.Directcostsrepresentthe value ing how specific component costs were estimated and the ofgoods,services,andotherresourcesconsumedinpro- datasourcesbeingusedforsuchestimates[8,25,26]. viding care due to an illness [13]. These include medical To investigate the reporting of component costs in the care expenditures associated with the diagnosis, treat- cost of foodborne illness literature, along with their rele- ment, and management of a disease in an individual. In- vant data sources, a review of the evidence is needed. direct costs represent productivity losses due to illness The scoping study, or scoping review, is one approach or death and intangible costs such as pain and suffering. used to survey the literature and aims to map the key Costs associated with overhead activities that are shared concepts underpinning a research area [27]. The frame- amongst individuals and expenditures incurred in the work for conducting a scoping review emphasizes that processofseekingcarearealsoindirectcosts.Operational the methods used throughout all stages of the process expenditures for healthcare facilities and personal trans- are conducted in a rigorous and transparent way. The portation costs are examples of indirect costs [14]. Costs process should be documented in sufficient detail to en- incurred at the population level are deemed societal costs ablethereviewtobereplicatedbyothers,andthisexplicit [8,9,12],which are costs that cannotbe completelyattrib- approach increases the reliability of the findings. Unlike a uted to an individual’s illness but can be incurred when a systematic review, a scoping study does not often lead to personoragroupofpeoplebecomeill[15].Societalcosts the statistical pooling of quantitative evidence from vari- primarily include expenditures incurred by industry and ous studies, as is often done in meta-analyses of system- government [16]. Component costs are the specific costs atic review data. While a scoping study uses an analytical thatmakeuptheabovecategories,andallofthe costsin- framework or thematic construction to present the evi- cluded in a COI estimate comprise the cost inventory for dence, there is no attempt made to present the weight or thatparticularstudy[17]. quality of evidence in relation to particular policies or in- Many studies employing a COI methodology have terventions[27,28]. demonstratedthatfoodborneillnessesgenerateaconsid- This study employed a scoping review methodology to erable disease burden andeconomicloss [11].According address the research question: “What are the component to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), costs and the respective data sources being used for esti- foodborne illness costs the United States economy be- mating the costoffoodborneillnessesinapopulation?” tween $10-83billion UnitedStatesdollars(USD) per year [18]. In Australia and New Zealand, the cost of food- Methods borne illness has been estimated at $1.289 billion and Scopingreviewmethodology $86 million USDrespectivelyperyear[14,19].InEurope, The scoping review framework published by Arksey and the annual cost of foodborne illness was estimated to be O’Malley in 2005 [27] includes 5 required stages which $171 million USD in Sweden [6] and $2 million USD in were followed in the present study. Many other scoping Croatia [20]. Many estimates for specific foodborne reviews have subsequently used this framework as a pathogens, or groups of pathogens, have been published guideline[29]. [4,21,22]. Although economic estimates for foodborne ill- ness have not been completed in Canada in the past Identifyingtheresearchquestion 20years[23],ithasbeenrecentlyestimatedthat4million The research team, consisting of academic and govern- episodes of domestically acquired foodborne illness occur ment researchers with expertise in the areas of food- annuallyinCanada[24]. borne illness and public health, jointly determined how Research has indicated that COI studies employ varied to synthesize the cost of foodborne illness literature methodological approaches, and that there is little through a series of in-person meetings. The government consistency in the cost inventories used in the COI lit- researchers also contributed as potential end-users of erature [7-10]. This is an issue when interpreting and the information obtained from a review in this area. The designing new COI studies, and also when comparing goals were to identify the different component costs that existing estimates for the same illnesses. When designing have been included when determining the cost of food- a study, it is difficulttodetermine which types ofcoststo borne illnesses, and to identify the data sources used to include (e.g., direct, indirect, societal), which component calculatetheseestimates. McLindenetal.BMCPublicHealth2014,14:509 Page3of12 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/509 Identifyingrelevantstudies used in thetitlesandabstractsofthe15studiesofknown Two comprehensive electronic databases were chosen relevance.Norestrictions were placed on date, country, for the literature search. The MEDLINE (PubMed) data- or language of publication during the searches. A broad base was used to identify studies from the human med- search approach (i.e., using infectious disease keywords) ical literature whereas studies from the animal health was used initially. This allowed for later refinement of literature werelocated in the AGRICOLA database. Prior the data extraction process to address the specific re- to the searches, 15 studies wereidentified by the research search question for the study reported herein. The‘peer- team as being highly relevant to a review in this area. reviewed’filter was unchecked in the AGRICOLA search. The identification of these studies following relevance All of the search results were imported into RefWorks screening was used to verify the comprehensiveness of Reference Management Software (ProQuest LLP, 2012), the search. Broad keyword searches were performed be- and duplicate citations were removed using the close and tween October 27th and November 1st 2012 to identify exact-matchfunctions. studies that addressed the COI of any infectious disease, including foodborne illnesses (Table 1). Search terms Studyselection were selected by extensive review of the terminology Prior toscreening,reviewerswereprovidedwith instruc- tional documents that outlined the objectives of the re- Table1Scopingreviewkeywordsearchstrategyto view and how the results would be presented (i.e., using identifycost-of-illnessstudiesforinfectiousdiseasesa empty shell tables). The 15 studies of known relevance Foodbornekeywords Communicablekeywords Costkeywords were also provided to the reviewers. Subsequently, titles Foodborneillness Communicable Cost and abstracts of 250 test studies were independently Foodborneillnesses Communicabledisease Costs screened by two reviewers, and also by a member of the research team. The 250 test studies were selected at ran- Food-borneillness Communicablediseases Cost-of-illness dom from those identified by the literature searches. Any Food-borneillnesses Communicableillness Costofillness disagreements during the testing stage were discussed Foodbornedisease Communicableillnesses Cost-of-illnesses by all 3 of the reviewers, and differences were resolved Foodbornediseases Infectious Costofillnesses byconsensus.Twolevelsofrelevancescreeningwereper- Food-bornedisease Infectiousdisease Costs-of-illness formed. Each level was based on reviews of the title and Food-bornediseases Infectiousdiseases Costsofillness abstractonly,withthesecondlevelofscreeningalsoserv- ing as a categorization step. Both levels of screening were Foodborneinfection Infectiousillness Costs-of-illnesses performed independently by two reviewers. The first Foodborneinfections Infectiousillnesses Costsofillnesses round of screening, which included all citations from the Food-borneinfection Transmissible Coi database searches, identified studies that described the Food-borneinfections Transmissibledisease DirectCosts COIofanyinfectious(communicable) disease, including Foodpoison Transmissiblediseases DirectCost foodborne illnesses, while excluding cost-effectiveness Foodpoisoning Transmissibleillness IndirectCosts studies for specific interventions. A standardized rele- vance screening tool was created in Microsoft Excel Foodbornepoison Transmissibleillnesses IndirectCost (Version 2007). A Cohen’s kappa coefficient was cal- Foodbornepoisoning Economic culated to establish a minimum level of agreement be- Food-bornepoison Economics tweeneachreviewerfollowingthefirstrelevancescreening Food-bornepoisoning Economy round. If the level of agreement was found to be poor Foodbornepathogen Economical (i.e., raised concerns among the reviewers), a third re- Foodbornepathogens Financial viewer would have been used and the first round of rele- vancescreeningwouldberepeated. Food-bornepathogen Monetary Studiesselectedafterthefirstroundofscreeningunder- Food-bornepathogens Money went a second level of screening, whereby each of the in- O157 Expenditure fectious and foodborne disease COI studies were further VTEC Expenditures classified into those that described the cost of foodborne STEC Dollar-value illnesses in humans, foodborne illnesses in animals, infec- O157:H7 Dollarvalue tious diseases in humans, infectious diseases inanimals, a combination of any of these categories, none of these Salmonella categories (thestudydidnotdescribethecostofaninfec- Campylobacter tious or foodborne illness), and as studies in which rele- aKeywordsineachcolumn(Foodborne,Communicable,Cost)werecombined vancecouldnotbedeterminedusingthetitleandabstract. withtheBooleanoperator‘OR’andtheneachofthecombinedcategories werefurthercombinedwiththeoperator‘AND’inthedatabasesearches. Following the second level of relevance screening, the McLindenetal.BMCPublicHealth2014,14:509 Page4of12 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/509 studyfocusedontheCOIoffoodbornediseasesinhumans Table2Descriptiveinformationofthe84costof only,andallothercategoriesofstudieswereexcluded.Re- foodborneillnessstudiespublishedbetween1972and sultsfromeachlevelofscreeningwerecomparedbetween 2012identifiedfromascopingreview reviewers and conflicts resolved by consensus through an Studytype No.ofstudies opendiscussion. Cost-of-illness 74 Notcost-of-illness(described 10 Chartingthedata componentcosts) Citations describing the cost of foodborne illnesses in Non-English(Excluded)a 10 humans (with or without other infectious illnesses) and Non-relevantstudies(Excluded)b 14 citations where relevance could not be determined using Regionof the title and abstract were retrieved in full text. A stan- publication dardized data-charting form was created in Microsoft NorthAmerica 43 Excel (Version 2007). Training for data extraction was Europe 29 performed using instruction forms and 7 full text stud- Asia 6 ies. Data extraction was conducted by two independent researchers, and the completed forms were compared Oceania 5 for comprehensiveness. Therefore, if one researcher ex- Africa 1 tracted data that the other had omitted, the study was SouthAmerica 0 re-examined by both reviewers, and differences in ex- Yearof tracted data wereresolved byconsensus. publication The data-charting form had two sections, the first for 2002-2012 36 gathering descriptive information on the relevant studies 1992-2001 31 (Table 2) and the second for gathering the data of inter- 1982-1991 15 est: the individual and societal level component costs in- 1972-1981 2 cluded in the studies and the data sources for those estimations(Tables3and4).Descriptivedataincludedin- Before1972 0 formation on the title of the study, whether it was avail- Foodborne No.included able in English, whether it directly estimated COI due to pathogens instudies one or more foodborne pathogens, and whether it de- 1.Non-typhoidalSalmonellaspp. 51 scribedthe componentcostsfor theestimate.Theyearof 2.Shiga-toxinproducingEscherichiacoli 34 publication,countryofpublication,andalistoffoodborne 3.Campylobacterspp. 27 pathogens included in the study were also collected. All 4.Vibriospp. 19 component cost data were extracted at the level of detail 5.Staphylococcusaureus 17 reported in each study rather than using pre-determined 6.Listeriamonocytogenes 16 categories for data extraction. Therefore, the specificity and detail in the extracted datawererepresentativeof the 7.Clostridiumperfringens 12 level of detail reported in the paper. The source of data 8.Salmonellatyphi 12 for each component cost was also collected, detailing 9.Clostridiumbotulinum 11 whether the data for the estimation came directly from a: 10.Shigellaspp. 10 survey, pre-existing databases, hospital records, an online Protozoaand 29 calculator (e.g., Economic Research Service of the United parasitesc States Department of Agriculture’s foodborne illness cost Virusesd 28 calculator)[30],theliterature,populationstatistics,census Other 24 data,outbreakdata,orexpertopinion. bacteriae aNon-Englishstudylanguages:Swedish(4),German(3),Italian(1),Danish(1), Collating,summarizing,andreportingtheresults Russian(1). The primary goal of this step was to refine the informa- bNon-relevantstudies:Didnotdescribecomponentcosts(i.e.,studiesthat wereidentifiedasrelevantthroughbothlevelsofscreening,butdidnot tion extracted from the studies into manageable group- providethedataofinterest). ings, or themes. Two researchers independently grouped cToxoplasmagondii(10),Cyptosporidiumspp.(7),Cyclosporacayetanensis(5), the componentcostandsourcedataextractedfromeach Trichinellaspp.(3),Giardialamblia(3),Taeniaspp.(1). dNorovirus(9),HepatitisA(6),Rotavirus(6),Astrovirus(4),Saprovirus(2), paper into themes and differences were resolved by con- Adenovirus(1). sensus throughout theprocess.Thegroupedinformation eYersiniaenterocolitica(8),Bacilluscereus(6),Brucellaspp.(4),Streptococcus spp.(4),Mycobacteriumbovis(1),Plesiomonasspp.(1). was summarized in categories of individual level (direct andindirect)andsocietallevelcomponentcosts. McLindenetal.BMCPublicHealth2014,14:509 Page5of12 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/509 Table3Individuallevelcomponentcostsanddatasourcesfrom84costoffoodborneillnessstudiespublished between1972and2012identifiedfromascopingreview Componentcosts Na Datasourcesb Directcosts H D L OC S O C P E M N/P N/A Medicalcosts 16 1 3 2 - - 3 - - - - 2 5 Treatmentcosts 14 4 2 3 - 1 - - - - 3 - 1 Drugcosts 29 3 3 6 1 3 2 1 - - 4 3 3 Prescription 18 3 3 1 - 6 - 1 - - 1 1 2 Over-the-counter 6 - 1 1 - 4 - - - - - - - Non-personaltransportation(ambulance) 12 1 1 3 1 - - - 1 2 1 - 2 Rehabilitation 10 - 1 3 1 - 1 1 - - 2 - 1 Materials(disposable/non-disposable) 7 1 2 - - 1 1 1 - - - 1 - Homevisits 5 - - - - - - - - - 1 3 1 Rehydrationtreatment 2 1 - - - 1 - - - - - - - Palliativecare 1 - 1 - - - - - - - - - - Laboratorycosts 20 5 3 2 1 2 1 - - 1 2 1 2 Pathogendiagnosisandanalysis 15 3 2 1 - 2 3 - - - 3 - 1 Ancillarydiagnostics 10 3 2 1 1 - 2 - - - - - 1 Laboratorysampling 7 1 1 2 - 3 - - - - - - - Personnelcosts 7 2 3 - - 2 - - - - - - - Physician 31 1 6 5 1 3 3 1 - 1 6 2 2 Generalpractitionerphysician 17 2 5 4 - 3 - - - - 3 - - Non-physician 2 - - - - 1 - - - - 1 - - Nurses 4 1 - 1 - - 1 - - - 1 - - Laboratorytechnician 3 1 - - - - 2 - - - - - - Consultants 7 - 1 2 - 1 2 - - - 1 - - Specialists 5 1 1 - - - - - - - 1 1 1 Hospitalservicescosts 46 5 6 11 1 2 5 1 - 1 7 3 4 Emergencyroom 14 4 3 1 - 1 - - - - 3 - 2 Intensivecareunit 5 1 1 - - - - 1 - - 2 - - Surgicalservices 3 - 1 - - - - - - - 1 - 1 Dialysis 2 1 1 - - - - - - - - - - Communityservices(out-patient)costs 11 - 3 1 - - - - - - 3 1 3 Long-termcareservicescosts 4 - 2 - - - - - - - - 1 1 Indirectcosts Productivitylosses 30 - 2 6 1 4 2 - - - 3 4 8 Duetosickleavefromwork(patient) 42 1 6 7 1 10 3 1 1 - 4 1 6 Duetocaringforothers(caregiver) 19 - 5 3 - 6 2 - - - 3 - - Duetocareofsickchildren 11 - 2 1 1 1 1 - - - 1 2 2 Lostleisuretime 14 - 3 6 1 - 1 - - - 1 - 2 Duetolong-termorpermanentdisability 8 - 1 2 - - 2 - - - 2 - 1 Patienttransportation(non-ambulance)costs 20 - 2 6 - 5 1 - 1 - 1 2 2 Forvisitorsandrelatives 6 - - 1 - 1 1 - - - 1 - 2 Parkingfees 1 - - - - 1 - - - - - - - Additionalcosts - - - - - - - - - - - - - Value-of-lifelost 29 - 1 15 1 1 1 - - - 3 2 5 McLindenetal.BMCPublicHealth2014,14:509 Page6of12 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/509 Table3Individuallevelcomponentcostsanddatasourcesfrom84costoffoodborneillnessstudiespublished between1972and2012identifiedfromascopingreview(Continued) Painandsuffering 21 - - 8 2 2 1 - - - 2 2 4 Riskaversionbehaviours 9 2 2 - 1 2 - - - - - - 2 Facility(operational)costs 9 1 2 2 1 - - - - - 2 1 - Non-medicalmaterials 7 - - 1 1 3 - - - - - 1 1 Totals 49 84 108 17 72 41 8 3 5 69 34 68 aCountsrepresentthenumberofstudiesreportingeachcomponentcostcategoryatthespecifiedlevelofdetail.Therefore,astudythatiscountedasincludinga higher-levelcategory(e.g.,treatmentcosts)cannotcontributeacounttoalower-levelcategory(e.g.,drugcosts)withinthesamegrouping,andviceversa. bD:Database,L:Literature,OC:OnlinecalculatorS:Survey,O:Outbreakdata,C:Census,P:Populationstatistics,E:Expertopinion,M:Multiple,N/P:Notprovided, N/A:Notapplicable. Tables 3 and 4 display the categories of direct and in- 7394 were excluded as they did not describe the COI of direct costs included at the individual level and the data anyinfectiousorfoodborneillnesses.Allofthe15studies sourcesusedforeachcomponentcostcategory. The cat- identifiedbytheresearchteamasbeinghighlyrelevantto egories were created based on the level of detail pro- a review in this area prior to the literature searches were vided in the study and thus, some categories represent identified by the employed search strategy. The Cohen’s more detailed sub-categories. Therefore, a study which kappacoefficientwas0.89forthe first relevance screen- included ‘medical costs’ did not explicitly describe any ing round, indicating substantial agreement between other direct costs included in their COI estimate. Simi- the two reviewers[32].Inthesecondroundofscreening, larly, all of the studies that were categorized as including the remaining 239 references were classified into 1 of 7 a broad component cost category (e.g., treatment costs, categories based on the type of COI that was estimated personnel costs, hospital service costs) were not counted (e.g., cost of foodborne illness in humans). Classifications towards including a more specific component in those for studies that fell into multiple categories, none of the categories. However, studies may have ultimately in- categories,orstudieswheretherelevancecouldnotbede- cluded these more specific costs in their estimates, but terminedwerealsoused. the components were unknown due to a superficial level Following the second round of relevance screening, ofreporting detail. references that focused on foodborne illness in humans, Data sources were grouped asfollows:ifthe authors of a combination of categories, and those where relevance a study stated that the literature was used for an esti- could notbedeterminedfrom thetitle andabstract were mate, the source of data was described as ‘literature’. selected(n=108).Tennon-Englishreferenceswereidenti- The original source of data in the cited literature may fied and excluded, as were an additional 14 studies that have been one of the other categories (e.g., a survey or did not provide any information on component costs. pre-existing databases), however, the cited literature was Therefore, 84 studies ultimately underwent data ex- not obtained to determine the actual data source. The traction. These studies described studies that directly esti- same principle applied for databases, population statis- mated the cost of foodborne illnesses and studies that tics, outbreak data, or census data that may have been describedcomponentcostsbutdidnotprovideanestimate. created using information from other data sources. This The majority of the studies (n=74, 88%) calculated resultedinpotentialoverlappingbetweendatasourcecat- the cost of a foodborne illness (or a group of foodborne egories, as only the immediate source of data was identi- illnesses) anddescribed the componentcostsincludedin fied in the present study. Cost calculators often provide the estimates (Table 2). Ten studies described compo- component cost estimates that have been amalgamated nent costs, but did not directly calculate the cost of a from a range of data sources, and are tools that can be foodborne illness. Papers in this latter category were used when estimating costs [31]. Sources of component foodborne illness prioritization studies, burden of food- cost data could also be described as not provided (N/P), borne illness reviews, and conceptual studies such as not applicable (N/A), or as ‘multiple’, meaning numerous cost of foodborne illness frameworks. Although the ob- componentcostsanddatasourcesweredescribedwithout jective of this group of studies was not to calculate the specifying which data sources were used for a particular cost of a foodborne illness, they did describe component componentcostestimate. costs and were therefore included. Data source identifi- cation was not applicable (N/A) for these ten studies. Of Results the 74 COI studies, 36 (49%) estimated the cost of a sin- Following duplicate removal, the MEDLINE (PubMed) gle foodborne pathogen while 38 (51%) examined mul- and AGRICOLA database searches yielded 7633 refer- tiple pathogens.Amongallincludedstudies(n=84),most ences to be screened for relevance (Figure 1). Of these, (80%)werepublishedinthelasttwodecades(1992–2012) McLindenetal.BMCPublicHealth2014,14:509 Page7of12 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/509 Table4Societallevelcomponentcostsanddatasourcesfrom84costoffoodborneillnessstudiespublishedbetween 1972and2012identifiedfromascopingreview Componentcosts Na Datasourcesb D L OC S O C P E M N/P N/A Industrycosts 10 3 3 1 1 - - - - - - 2 Lossestobusinesses 13 1 2 - 1 1 - - - 2 2 4 Reducedproductdemand 7 - 3 - 1 - - - - 1 - 2 Advertisingtoregaincustomertrust 6 1 2 1 - - - - - - - 2 Lossestofoodserviceestablishments 5 - 2 - - 1 - - - 1 - 1 Productspoilage 4 - 1 - - 1 - - - - - 2 Productrecall 11 - 3 1 2 - - 1 - 1 - 3 Farm-relatedcosts 3 - 2 - - - - - - - - 1 Herdslaughter 4 - 1 1 - - - - 1 - - 1 Farmerscompensation 2 2 - - - - - - - - - - Increasedtimetomarket 2 - 1 1 - - - - - - - - Adjustedmanufacturingprocedures 9 - 3 - 2 1 - - - 1 - 2 Plantclosureandbankruptcy 6 - 2 - 1 1 - - - 1 - 1 Equipment 5 1 2 - - - - - 1 1 - - Publichealthcosts 5 2 - - 1 - - - - - - 2 Outbreakinvestigationcosts 15 - 5 - 4 2 - - - - - 4 Laboratorytesting 10 1 3 - 1 2 - - - 1 - 2 Personnel 7 - - - 1 4 - - - 1 - 1 On-sitetreatment 3 - 2 - - - - - - - - 1 Cleanup(includingfooddestruction) 3 - 3 - - - - - - - - - Consumables 3 - - - 1 2 - - - - - - Administration 2 1 - - - 1 - - - - - - Sourceidentification 2 - - - 1 1 - - - - - - Make-shiftfoodservices 2 - - - - 2 - - - - - - Travel 2 - - - - 1 - 1 - - - - Prevention 6 2 - - - - - - 1 - - 3 Surveillance(includingdatabasecreation) 11 2 5 1 1 - - - - 1 - 1 Educationalcampaigns 7 - 2 1 - - - - - 1 2 1 Research 6 2 1 - - 1 - - - 1 - 1 Vaccinationprograms 2 - 1 - - - - - - - - 1 Legalcosts 6 1 1 - 1 1 - - - 1 - 1 Productliabilitysuits 5 - 2 - 1 1 - - - - - 1 Insurance-related 4 - 2 - - 1 - - - 1 - - Victim(individual)settlements 3 - - - - - - - - - - 3 Classaction(group)settlements 1 - - - - - - - - - - 1 Out-of-courtsettlements 1 - - - - - - - - 1 - - Prosecutioncostsfrompublicfunds 1 - - - - - - - - - - 1 Jailsentences 1 - - - - - - - - 1 - - Governmentandregulatorycosts 7 2 - - 1 1 - - 1 1 - 1 Regulatoryfinesandenforcement 6 - 2 1 - - - 1 - 1 - 1 Localauthorityinvestigations 5 1 1 - 2 - - - - - - 1 Publicinquiry 1 - - - - - - 1 - - - - McLindenetal.BMCPublicHealth2014,14:509 Page8of12 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/509 Table4Societallevelcomponentcostsanddatasourcesfrom84costoffoodborneillnessstudiespublishedbetween 1972and2012identifiedfromascopingreview(Continued) Policyimplementationandmonitoring 1 - - - - - - - - - - 1 Totals 22 57 8 23 25 0 4 4 19 4 49 aCountsrepresentthenumberofstudiesreportingeachcomponentcostcategoryatthespecifiedlevelofdetail.Therefore,astudythatiscountedasincludinga higher-levelcategory(e.g.,industrycosts)cannotcontributeacounttoalower-levelcategory(e.g.,productrecall)withinthesamegrouping,andviceversa. bD:Database,L:Literature,OC:OnlinecalculatorS:Survey,O:Outbreakdata,C:Census,P:Populationstatistics,E:Expertopinion,M:Multiple,N/P:Notprovided, N/A:Notapplicable. in North America (51%) and Europe (35%). The 10 most individual level costs only, while 10 (12%) studies de- frequently estimated costs were those due to illnesses scribeddirectcostsexclusively.Threestudiessolelyexam- caused by bacterial foodborne pathogens, with non- ined the societal costs associated with foodborne illness. typhoidalSalmonellaspp.(n=51,i.e.,COIforthispatho- The remaining studies described both societal and direct gen was reported in 51 of 74 studies estimating costs), individual costs (n=2) or societal and indirect individual shiga-toxin producing E. coli (n=34), and Campylobacter costs(n=2). spp. (n=27) being the most commonly studied. Add- The direct individual level component costs most often itional bacterial foodborne pathogens were included in included werebroadly described as hospital services costs multiple studies (refer to footnotes of Table 2), as well as (n=46) without explicitly describing which hospital ser- foodborneviruses,protozoa,andparasites. vice costs they estimated (e.g., emergency room costs, in- Among the 84 studies included in the review, 40 (48%) tensive care costs, surgical services costs, dialysis costs). studiesdescribedbothindividual(directandindirect)and Physiciancosts,acomponentofpersonnelcosts,werecom- societal level costs. Twenty-seven (32%) studies described monly included (n=31) along with drug costs (n=29), a MEDLINE via PubMed AGRICOLA Human medical literature Animal health literature h (n = 7361) (n = 916) arc Se Recordsafter duplicateremoval (n = 7633) 1 d n u o R Recordsscreenedin Records excluded in ng round 1 round 1a Screeni (n = 7633) (n = 7394) d 2 Records screenedin Study classification n round 2 u o (n = 239) 1. Foodborne illness in R g humans (n = 79) n 2. Foodborne illness in Screeni Studies retrieved a3hn.uimmInaafnelssc t((inno u==s 28d)6is)eases in (full-text) 4. Infectious diseases in Fulel-xtcelxutd setuddbies -Foodborne illness in 5an. imCoamls b(nin =at i1o7n) of (n = 24) humans categories (n = 23) -Combination of 6.None of these categories categories (n = 26) -Relevance could not be 7. Relevancecould not be determined determined by title and (n = 108) abstract (n = 6) d de u ncl Studies included in I data extraction (n = 84) Figure1Scopingreviewflowchart.aStudieswereexcludedastheydidnotdescribetheCOIofanyinfectiousorfoodborneillnesses.bTen non-Englishreferenceswereexcluded(4Swedish,3German,1Italian,1Danish,1Russian),aswereanadditional14studiesthatdidnotprovide anyinformationoncomponentcosts. McLindenetal.BMCPublicHealth2014,14:509 Page9of12 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/509 component of treatment costs. Other studies described sources being used in the published cost of foodborne ill- these and other costs at a greater depth (e.g., prescription nessliterature wasobserved.Rather thanbeingguided by andover-the-countercostsasacomponentofdrugcosts), ahighlyspecificresearchquestionandparticularstudyde- and there was substantial variation in the specificity and signs,ascopingreviewisguidedbythebroadrequirement detail among studies when describing component costs. ofidentifyingallrelevantliteraturethatpertainstothere- The most commonly reported indirect component cost search question [27]. Due to the potential usefulness of wasproductivitylossesduetosickleavefromwork(n=42). COI studies to inform decision makers, it is important A large number of studies included a cost estimate for that COI estimates are derived in a uniform, consistent, ‘productivity losses’ without specifically stating which and transparent manner [12,25,26]. To address the issues individualwasexperiencingthelossofoutput(e.g.,thepa- ofuniformity incostinventories and transparencyin data tient or caregiver) (n=30). The value-of-life lost was source usage, a better understanding of which cost com- estimated in 29 studies while costs broadly described ponents are included and how they are described in the as ‘personal transportation’ expenses were calculated in publishedcostoffoodborneillnessliteratureiscritical. 20studies. MoststudieswerebasedinNorthAmericaandEurope, Prior estimates published in the literature were the indicating that the results are more applicable to devel- most commonly used source of individual level compo- oped country contexts and may not represent foodborne nent cost data (used 108 times), followed by databases illness component costs and data sources in developing (84 times) and surveys (72 times). Multiple sources were nations.Thismaybeduetoalackofresourcestoconduct listed for component cost estimates on 69 occasions. COI studies or it may be a reflection of other infectious These studies included a description of multiple compo- diseaseprioritiesfordevelopingcountries.Themajorityof nent costs and data sources without specifying which the cost of foodborne illness studies identified have been data sources were used for a particular component cost published in the past two decades (1992–2012), which estimate. No data sources were provided for component is a trendobservedinallCOIliterature[14].The10most cost estimates 34 times, and data sources were not ap- frequently estimated costs were those due to illnesses plicable for 68 of the component costs. These compo- caused by bacterial foodborne pathogens. This was ex- nent costs came from the 10 studies that didnot directly pectedasthesepathogensarecitedascarryingalargebur- estimateacostoffoodborneillness. den in terms of the number of illnesses, hospitalizations, Thesocietallevelcomponentcoststhatweremostoften anddeaths[17]. included in cost of foodborne illness studies were out- The primary results from this study are the reporting break investigation costs (a component of public health patterns ofcomponent costs in the cost of foodborne ill- costs, n=15),lossesincurredbybusinesses (acomponent nessliteraturealongwiththesourcesofdataforeaches- of industry cost, n=13), costs associated with product timate. In regards to the breadth of cost inventories, recall (a component of industry costs, n=11), and costs almost half of the studies (48%) included individual level related to public health surveillance of foodborne illness costs(directandindirect)andsocietallevelcostsintheir (n=11) (Table 4). Other societal costs included in some estimates. This indicated that many studies are estimat- studies were legal costs and government related (regula- ing a wide spectrum of costs associated with foodborne tory)costs. illnesses. Fewer studies included societal costs compared Similar to the individual costs, prior estimates pub- toindividualcosts.Societallevelcostsmaybemoredifficult lished in the literature were the most commonly used to calculate, as attributing costs incurred at the population source of component cost data for societal costs (used level due to a particular illness might be more challenging 57 times). Outbreak data, surveys, and pre-existing data- thanestimatingadirectorindirectcostassociatedwithan baseswereused25,23,and22timesrespectively.Multiple individualperson[33].Additionally,societalcostsmaynot sourceswerelistedfor19componentcosts.Thesestudies beapplicablegivena study’sperspective(e.g.,astudyesti- described numerous component costs and data sources mating healthcare-related costs may omit societal costs). withoutspecifyingwhichdatasourceswereusedforapar- In the 84 studies included in the review, there was a high ticular component cost estimate. No data sources were levelof variabilityinthereportingdetailofindividualand provided for component cost estimates 4 times, and data societal level component costs. For instance, 16 studies sourceswerenotapplicableon49occasions. broadly included ‘medical costs’ in their estimates as the onlyindividualdirectcost,while the remainder of stud- Discussion ies estimating directcostsincludedmorespecificcompo- This scoping review explored component costs of food- nentsofmedicalcostssuchas treatmentcosts, laboratory borne illness and sources of data for the cost estimates. costs, personnel costs, hospital service costs, community Highvariabilityintermsofthedepthandbreadthofindi- services costs, and long-term care services costs. Nu- vidual and societal level cost components and the data merous papers provided even greater detail, with studies McLindenetal.BMCPublicHealth2014,14:509 Page10of12 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/509 delineating particular components in these broader cat- individual and societal costs, multiple sources were listed egories. For example, specific treatment-related compo- for 88 component costs across 14 different studies. These nentssuchasdrugandrehabilitationcostsweredescribed studies described numerous component costs and data in certain studies. The variability in reporting detail sources without specifying which data sources were used can also be seen in the indirect individual and societal for a particular component cost estimate. Data sources levelcosts,whichindicatesthatalthoughagreaterlevelof were not provided for 38 individual and societal level specificity can be achieved when calculating component component costs, meaning that an estimate was included costs, certain studies electtoestimate costs more superfi- without any explanation of where it came from or how it cially. This is an issue because it does not allow the end- was deduced. These are issues of inadequate reporting user of a COI study to fully understand which types of thatinhibitsrepeatabilityoftheseestimates. costs were included in an overall estimation. In turn, this Proponents of COI research have cited that one of the makestheeconomicburdenofanillnessmoredifficultto major strengths of these studies is the potential to com- interpret and understand and reduces the feasibility of pare one estimate to another [12,25]. In an era where meaningfullycomparingtwostudiesforthesamedisease. evidence-informed decision making is at the forefront, The component costs presented in Tables 3 and 4 were synthesizing the evidence from high quality studies is an aggregated from all of the relevant cost of foodborne ill- important step in making an informed decision [34]. nessstudiesidentifiedduringthereview.However,certain Numerous studiesdating backto1982havestressedthat costs may only be relevant for a particular pathogen or researchers should standardize their COI methodologies chronic sequelae. An example of this would be intensive toimprovetheconsistencyandcomparabilityofestimates care unit (ICU) costs incurred due to shiga-toxin produ- [12,13,26].Thesestudiesclaimthatiftwootherwise com- cing E. coli infections, which may not be as relevant to parable studies have included different components when other foodborne illnesses. A future study could deter- estimatingacostofanillness,itwouldnotbemeaningful mine which costs are pathogen-specific and which are to compare them. If researchers continue publishing cost commonly included across all foodborne illnesses. Add- of foodborne illness studies while using different cost in- itionally, of the 74 COI studies, 36 estimated the cost of ventories(i.e.,studieswhichcontainawiderangeofcom- a single foodborne pathogen while 38 examined mul- ponent costs reported with varying levels of detail), this tiple pathogens. Further research could determine if the trend of insular estimates with limited comparability will component cost inclusion and reporting detail differs in continue. Therefore, the research community engaging in single-versus multiple-pathogen studies, and to explore COI studies may benefit from a discussion of minimum the implications of this factor when comparing or com- criteria for component cost and data source reporting. biningCOIestimates. This scoping review illustrates the breadth of published A further consideration is the impact of data sources cost inventories in the cost of foodborne illness literature on acost offoodborne illness estimate. A wide variety of andthedepthtowhichtheyhavebeenreported.Byusing data sources were used to estimate component costs of this scoping review as evidence that there is a lack of foodborne illness. Certain data sources may be more standardization in cost inventories in the cost of food- credible than others. For example, it could be argued borne illness literature, and to promote greater transpar- thatcostsestimatedbyexpertopinionaremoresubjective ency and detail of data source reporting, there will be an than estimates taken from hospital records. Future re- increase in cost of foodborne illness research that can be search could compare specific component cost estimates interpretedandcomparedinameaningfulway. foraparticularpathogenusingvaryingdatasourcestode- During the literature search, a formal search of the terminetheimpactofusingdifferentsourcesofdata.How- grey (unpublished) literature was not conducted. How- ever, because there was an overlapping of data sources ever, the peer-reviewed filter was left unchecked during (e.g., an estimate taken from the literature may have theAGRICOLAdatabasesearchandrelevantgreylitera- come from a survey), data source variability may be less ture identified at this stage was included in the review. substantial than it appears, as only the immediate source Also, by only searching a single animal health-related of data was identified in the present study. Additionally, database (i.e., AGRICOLA), the number of studies iden- when a study reports a data source (e.g., the literature) tified as describing the cost of foodborne and infectious without identifying the origin of the information, which illnesses in animals may be an underestimation. How- may in fact be another data category (e.g., a survey, hos- ever, we do not believe that this has biased the results, pital records, pre-existing database), it does not allow as the study reported herein focused on costs related to the reader to easilyevaluatetheappropriatenessorvalid- foodborne illnesses in humans only. Non-English lan- ity of the data source for the estimate. Also of concern guage papers were excluded from the present study, and is the number of component cost estimates that could therefore, these resultsmay only be applicableto English not be linked to a particular source of data. For both speaking countries. Lastly, an optional stage (step 6) in

Description: