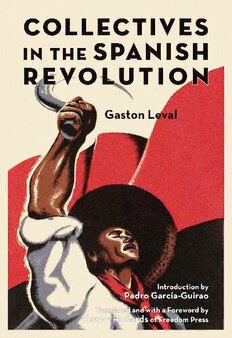

Collectives in the Spanish Revolution PDF

Preview Collectives in the Spanish Revolution

Collectives in the Spanish Revolution Gaston Leval Translated from the French by Vernon Richards Collectives in the Spanish Revolution Gaston Leval Translated from the French by Vernon Richards This edition © 2018 PM Press All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. ISBN: 978–1–62963–447–0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017942919 Cover by John Yates / www.stealworks.com Interior design by briandesign 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 PM Press PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 www.pmpress.org Printed in the USA by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan. www.thomsonshore.com CONTENTS preface to the 2018 edition v introduction ix foreword 7 PART ONE PREAMBLE i The Ideal 17 ii The Men and the Struggles 39 iii Material for a Revolution 58 iv A Revolutionary Situation 70 PART TWO AGRARIAN SOCIALISATION v The Aragon Federation of Collectives 83 1. Graus 92 2. Fraga 104 3. Binefar 113 4. Andorra (Teruel) 121 5. Alcorisa 129 6. Mas de las Matas 136 7. Esplus 143 vi Collectives in the Levante 148 General Characteristics 148 1. Carcagente 159 2. Jativa 165 3. Other Methods of Operation 173 vii The Collectives of Castile 178 viii Collectivist Book-Keeping 191 ix Libertarian Democracy 204 x The Charters 214 PART THREE INDUSTRY AND PUBLIC SERVICES xi Industrial Achievements 223 1. Syndicalisations in Alcoy 231 xii Achievements in the Public Sector 240 1. Water, Gas and Electricity in Catalonia 240 2. The Barcelona Tramways 245 3. The Means of Transport 253 4. The Socialisation of Medicine 264 PART FOUR TOWNS AND ISOLATED ACHIEVEMENTS xiii Town Collectivisations 279 1. Elda and the S.I.C.E.P. 280 2. Granollers 284 3. Hospitalet de Llobregat 289 4. Rubi 296 5. Castellon de la Plana 300 6. Socialisation in Alicante 306 xiv Isolated Achievements 312 1. The Boot and Shoemakers of Lerida 313 2. The Valencia Flour Mills 314 3. The Chocolate Cooperative of Torrente 315 4. The Agrarian Groups in Tarrasa 316 PART FIVE PARTIES AND GOVERNMENT xv Political Collaboration 321 xvi Libertarians and Republicans 327 xvii The Internal Counter-Revolution 329 PART SIX EPILOGUE xviii Final Reflections 339 bibliographical notes 357 about the authors 369 index 371 preface to the 2018 edition Collectives in the Spanish Revolution can only deal in any detail with some of the self-managed collectives that were established in Republican Spain during the struggle against Franco, for, as the author points out, there were 400 agricultural collectives in Aragón, 900 in Levante, and 300 in Castile. In addition, the whole of indus- try in Catalonia and 70 per cent in Levante was collectivised. Leval’s study brings together two aspects that are generally dif- ficult to unite—analysis and testimony—but, and in part owing to this method of presentation, the reader’s interest is held throughout the book. He visited the towns and villages of revolutionary Spain where, soon after July 19, 1936, people had opted to live a libertar- ian communist lifestyle almost without precedent in all history, col- lectivising the land, factories and workshops, and the social services. He paints a serene but not uncritical picture of the role of the countless rank-and-file activists of “the idea” who had long discussed the possibilities of a self-managed economic and social system that was truly communal and anti-authoritarian: It is clear, the social revolution which took place then did not stem from a decision by the leading organisms of the C.N.T. or from the slogans launched by the militants and agitators who were in the public limelight. . . . It occurred spontane- ously, naturally, not (and let us avoid demagogy) because “the people” in general had suddenly become capable of per- forming miracles . . . but because, and it is worth repeating, among those people there was a large minority who were active, strong, guided by an ideal which has been continuing v collectives in the spanish revolution through the years a struggle started [more than half a century earlier] in Bakunin’s time (p. 80). This raises the question: were the collectivisations enforced at the point of a gun, as argued by a number of bourgeois historians? In fact, in most villages collectivisations occurred after the major landowners had fled to the Francoist zone: usually, assem- blies were held at which it was decided to expropriate the land- owners’ land and machinery and share their own for the common good; teams were formed to carry out the necessary tasks, each electing recallable delegates to a village assembly. Leval writes that in Aragón, where the libertarian militias were numerous, their role was minimal if not negative inasmuch as they lived, in part, at the expense of the collectives. As he describes it, they “lived on the fringes of the task of social transformation being carried out,” although Durruti, realising their importance, did send some of his men, skilled organisers not armed troops, to help the collectives. All the energy, however, came from the local militants who took initia- tives “with a tactical skill often quite outstanding” (p. 91). Other chapters make fascinating reading: “The Socialisation of Medicine,” “The Charters,” “Rubi,” “Lerida,” etc. The agricul- tural, industrial and social service industries are all explained with their own peculiar aspects, and their development traced within the overall scheme of self-management. A number of points deserve separate study, such as the problem of the relationship of individuals to their work in a new society: “Obviously some would have preferred to stay in bed, but it was impossible for them to cheat” (p. 117); “there was no place in the rules for the demand for personal freedom or for the auton- omy of the individual” (p. 125); “Building operatives were working with enthusiasm. They had started off by applying the eight-hour day, but the peasants pointed out they worked a twelve-hour day” (p. 146 and also pp. 211, 212, 304). Some of the author’s comments are well off track: “his Slavonic psychology, his generous Russian nature” (p. 18 on Bakunin, but Lenin too was a Russian), “preaching the libertarian gospel” (p. 47), vi preface to the 2018 edition “the Good News” (p. 56), but fortunately they are few and make no difference to the essence of Leval’s story. More curious, however, is Leval’s position: “convinced very soon that the anti-fascists would end by losing the war” (p. 68), he dedi- cated himself to collecting together the results of this unique experi- ment for posterity. There are contemporary articles written by Leval: “I had to make an effort to give them confidence and offered them words of hope” (p. 112). We cannot but underline Leval’s patronising hypocrisy in this matter—a sort of tourist’s eye view of the attempts to live of the condemned. What was there to do? Leval seems to be trying to be a historian first and anarchist second, overlooking that it is always one and the same struggle: “Posterity is us, just later on.” There are, in fact, two faces to Leval. In one chapter entitled “Political Collaboration” he writes, “This excursion in the corridors of power was negative” (p. 324). But while he was in Spain, during the Civil War, that was not Leval’s opinion at all. On arrival he published an article in Solidaridad Obrera (November 27, 1936, p. 8) entitled “Discipline: A Condition of Victory”; in February 1937 he took part in a meeting with Mariano R. Vázquez (a strong supporter of CNT participation in the government) and again in France in November 1937, in Le Libertaire, he pleaded for a moratorium on the anarchist programme for the duration of the war. Leval also published articles of a practical nature, such as: “The Small Proprietor and the Small Business,” “Our Programme for Reconstruction,” “Let Us Establish Co-operatives,” (Solidaridad Obrera, December 12, 1936, p. 4; December 27, 1936, p. 10; March 2, 1937, p. 6). His stand in support of the pro-governmental section of the CNT is important. Before the war Leval was better known for his books on social reconstruction, written in the spirit of Peter Kropotkin’s The Conquest of Bread but adapted to the epoch. Many of the collectivists knew Leval from these writings and had he defended at the time the position he takes in Collectives then the opposition to the political sidetracking that was going on could well have been far greater. Interesting too is that the translator and publisher of the origi- nal 1975 English-language edition, Vernon Richards, fails to point vii collectives in the spanish revolution out this evolution in Leval’s thinking. It would also have been useful to know that Sam Dolgoff, author of The Anarchist Collectives: Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939, took his texts from the 1952 Italian edition of Leval’s book, with varia- tions. (The figures, for example, given in the chapter on the sociali- sation of medicine are different from Richards’ translation. Are they typographical errors by Dolgoff or forgetfulness on the part of Richards?) Other texts, in particular “The Characteristics of the Libertarian Collectives,” an excellent résumé of the nineteen points of the main aspects of self-management, as well as the section of the 1948 Italian pamphlet L’attivita sindicale nella transformazione sociale that deals with industry, should have been included in the 1975 edition but for some reason Leval and Richards chose not to do so. Collectives in the Spanish Revolution demonstrates clearly that the working class are perfectly capable of running farms, factories, workshops, and health and public services without bosses or manag- ers dictating to them. It proves that anarchist methods of organising, with decisions made from the bottom up, can work effectively in large-scale industry involving the coordination of many thousands of workers in many hundreds of places of work across numerous different cities and towns, as well as broad rural areas. The Spanish Revolution also gives us an insight into the creative and construc- tive power of ordinary people once they have some control over their lives. The Spanish working class not only kept production going throughout the war but in many cases managed to achieve increases in output. They improved working conditions and created new techniques and processes in their workplaces. They created, out of nothing, an arms industry without which the war against fascism could not have been fought. The Revolution also showed that without the competition bred by capitalism, industry can be run in a much more rational manner. Finally it demonstrated how the organised working class inspired by a great ideal has the power to transform society. Stuart Christie January 2018 viii INTRODUCTION The only constructive, valid, important achievement during the Civil War was in fact that of the Revolution, on the fringe of power. The industrial collectivisations, the socialisation of agriculture, the syndicalisations of social services, all that, which made it possible to hold out for nearly three years and without which Franco would have triumphed in a matter of weeks, was the achievement of those who created, organised without concerning themselves with ministries and ministers. Gaston Leval, Collectives in the Spanish Revolution 1 More than eight decades ago revolutionary Spain implemented a massive model of worker-controlled agriculture, industry and public services based on libertarian communism and collectives in the midst of the Civil War. Workers had to do so under the threat posed by Francoist troops, the Communist persecution of anarchists,1 the active boycott of the most conservative policies established by the Spanish Second Republic,2 and the scarcity brought about by the conflict. The experiment only lasted for a brief time in the Republican zone, but the world is still fascinated 1 “The brigade led by the communist Lister was soon to abandon the front to go and destroy ‘manu militari’ almost all the Aragonese Collectives, including that of Binefar and its canton” (p. 121). 2 “It was not an easy matter to assert themselves so as to avoid friction among the anti-Francoist sectors. For the socialist, republican, and communist politi- cians actively sought to prevent our success, even to restoring the old order or maintaining what was left of it” (p. 239). ix