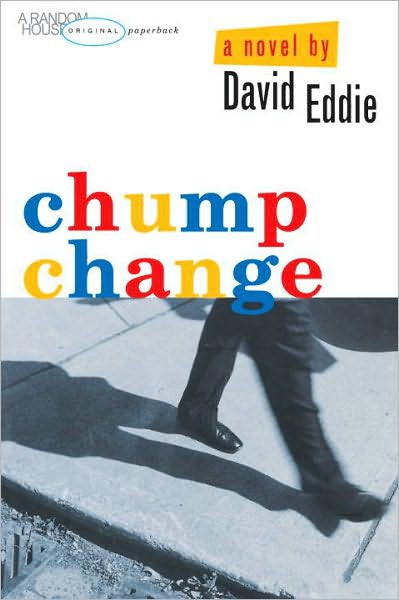

Chump Change PDF

Preview Chump Change

It's hard to claim literary burnout after a brief stint as a glorified filing clerk at Newsweek, but the slacker protagonist of Eddie's debut novel, 28-year-old, double-M.A., would-be writer David Henry is at least singed enough to flee New York for hometown Toronto. Arriving at the airport with only a pocketful of change, David embarks on a spiral of awful jobs and unsuitable girlfriends as he tries to fake an adult life and dodge tuition loan officers. At least he doesn't have to live with his parents, and his first roommate is the erstwhile object of his unrequited college love, Leslie Lawson. Roommate she remains, though, and his first Toronto girlfriend is a persistent Korean with a penchant for Les Miserables and white pumps. Careerwise, David fails as a freelance magazine writer, movie extra and an assistant to an administrative assistant, but strangely enough, it is success, in the form of a $40,000-a-year job as newswriter for the CBC (aka Cosmodemonic Broadcast Corporation) and a luscious 19-year-old bartender girlfriend, that finally causes him to hit rock bottom. Eddie mines his charmingly self-absorbed antihero's pratfalling career for all it's worth, but despite the novel's willingness to amuse, the humor is hit-or-miss. The half-ironic, half-sentimental tone owes something to Jay McInerney and Douglas Coupland, and Eddie proves an amusing writer who here fails to probe deeper than his conventional bildungsroman theme.

Copyright 1999 Reed Business Information, Inc.

This is a Henry Milleresque tale about a young writer (the author's alter ego, David Henry) who quits his job as a letter clerk at Newsweek and decamps New York for the friendlier environs of Toronto. There, amidst various escapades and seductions, he obtains a freelance job writing an observation piece about Toronto for Canada's premier political/cultural journal. This leads to a job as a newswriter for the CBC, which, in a gratuitous salute to Miller, the author dubs the Cosmodemonic Broadcast Corporation. Unfortunately, Toronto is not Paris, nor is the author's style as lively or as cynical as Miller's, though some of his protagonist's observations about modern civilization and the rise and decline of the written word are interesting. Eventually the protagonist's self-destructive urges, so clearly laid out at the outset of the novel, get the better of him, and he finds himself in that "fallen" state of freedom to which he has aspired all along--a rejuvenation of the Milleresque happy-go-lucky character. Frank Caso