Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century: T'ien-kung K'ai-wu PDF

Preview Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century: T'ien-kung K'ai-wu

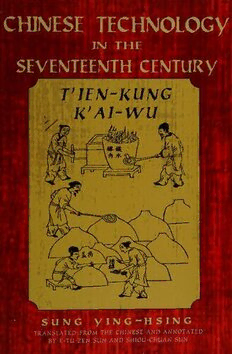

CHINESE gas iVee lkeve; Thiv THE S a ¢ SEVENTEENT Hc en T/IEN-KUNG oy, ‘a WU. 7/98 EBOOKS | $1.43 GEN sr TECHNOLOGY FINS EET E SEEN EEN PEECEN TURY T'IEN-KUNG KAI-WU SUNG YING-HSING TRANSLATED FROM THE CHINESE AND ANNOTATED BY E-TU ZEN SUN AND SHIOU-CHUAN SUN B= m DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC. MINEOLA, NEW YORK Copyright Copyright © 1966 by E-tu Zen Sun All rights reserved under Pan American and International Copyright Conventions. Published in Canada by General Publishing Company, Ltd., 30 Lesmill Road, Don Mills, Toronto, Ontario. Published in the United Kingdom by Constable and Company, Ltd., 3 The Lanchesters, 162-164 Fulham Palace Road, London W6 9ER. Bibliographical Note This Dover edition, first published in 1997, is an unabridged republication of the work first published by The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park and London, in 1966. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sung, Ying-hsing, b. 1587. [Tien kung k’ai wu. English] Chinese technology in the seventeenth century ; Chinese tech- nology in the seventeenth century. Sung Ying-hsing ; translated from the Chinese and annotated by E-tu Zen Sun and Shiou- chuan Sun. p. cm. Originally published: University Park : Pennsylvania State University, 1966. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-486-29593-1 (pbk.) 1. Technology—China—History—17th century. 2. Science— China—History—17th century. I. Sun, E-tu Zen, 1921— II. Sun, Shiou-chuan, 1913- III. Title. T27.C5S9313 1996 600—dc21 96-53237 CIP Manufactured in the United States of America Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501 CONTENTS Translators’ Preface Author’s Preface to the 1637 edition PART I Chapter 1, The growing of grains Chapter 2, Clothing materials 35 Chapter 3, Dyes 1&5) Chapter 4, The preparation of grains 81 Chapter 5, Salt 109 Chapter 6, Sugars 124 PART I 135 Chapter 7, Ceramics Chapter 8, Casting 159 Chapter 9, Boats and carts 171 Chapter 10, Hammer forging 189 Chapter 11, Calcination of stones 201 Chapter 12, Vegetable oils and fats 215 223 Chapter 13, Paper ili CONTENTS PART III Chapter 14, The metals 235 Chapter 15, Weapons 261 Chapter 16, Vermilion and ink 299 Chapter 17, Yeasts 289 Chapter 18, Pearls and gems 295 Bibliography A (Chinese sources) 311 Bibliography B (non-Chinese sources) 321 Glossary 339 Appendix A (Summary of Chinese dynasties) 357 Appendix B = (The twenty-four Chinese solar terms) 360 Appendix C = (Equivalence of Chinese weights and measures in metric units) 362 Appendix D (Transmission of certain techniques from China to the West) 364 Index 369 TRANSLATORS’ PREFACE Nearly ten years ago, in the course of research on a point of Chinese economic history, the translators had occasion to consult T’ien-kung k’ai-wu. Its special quality made us realize how limited was our own knowledge of traditional Chinese technology. It occurred to us, as we enthusiastically pored over this work, that others might share our interest. T’ien-kung k’ai-wu, which may be rendered as “The Creations of Nature and Man,” is by no means the only or the oldest Chinese work on technological subjects, but while other works dealt with individual subjects, the present book covers practically all the major industrial techniques of its time, from agricul- ture, textiles, mining, metallurgy, and chemical engineering, to the building of boats and the manufacture of weapons. Professor Joseph Needham, author of the monumental treatise on Science and Civilization in China, calls it “an important book on industrial technology” of the early seventeenth century by “the Diderot of China, Sung Ying-hsing.” The original preface was dated 1637, but only a bare outline of the author’s life can be reconstructed from presently available sources.’ Sung’s early years were typical of those of a young man of a scholar-official family. He was born, probably shortly before the end of the century, in Feng-hsin, Kiangsi Province. In his youth he received the usual classical education and passed the public examinations to the level of a provincial graduate in 1615. Thereafter he served in a number of official capacities in several provinces, including his native Kiangsi. It was there, while serving as the Education Officer of Fen-i district, that he wrote the present book. In addition to T’ien-kung k’ai- wu, Sung wrote a work on phonology, and a collection of critical essays, but these have been lost. After the fall of the Ming dynasty in 1644 Sung, together with his elder brother Ying-sheng, retired to his native home and led a secluded life. The probable date of his death is placed at around 1660 by V. K. Ting. In the early years of Manchu rule, as he wrote a short biography of his brother Ying-sheng, who had taken his own life because of acute depression over the fall of Ming, Sung Ying-hsing could hardly have dreamed that it was he himself who was to achieve greater renown three centuries later. Neither could he have foreseen that, decades after the “alien” Manchu rulers had been overthrown, there would be a keen and widespread interest, both in China and abroad, in the technological history of the country, and that T’ien-kung k’ai- wu would benefit many scholars other than his book-bound contemporaries whom he so impatiently chided in the Preface. Although outstanding in scope and factual details, Sung’s was not the only Vv TRANSLATORS’ PREFACE book on science and technology produced in his period. At the end of the Ming dynasty (late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries) many inquiring minds among the literati were rebelling against the futility of the idealist school of thought of Wang Yang-ming, and the result was the upsurge of interest in the materialistic aspects of life and the publication of several works of a factual and technological character that have since become classics in their fields. The seventeenth century as a whole saw the strengthening of this trend, which culminated in the thought and teachings of Wang Fu-chih and Yen Yuan and later in Tai Chen. Yen Yuan, the master of pragmatic philosophy, and Sung Ying-hsing would have found each other congenial; Yen planned for the curriculum of the Chang-nan Academy, of which he was the director for a short period in 1696, courses on military and industrial techniques in addition to those on classical studies.* When we compare Yen’s plan with the 1637 Preface of T’ien-kung k’ai-wu, the similarity of intent is obvious. Apart from the atmosphere of general reaction against idealist thought, the actual condition of Ming society must have helped inspire Sung’s book. Since the latter part of the sixteenth century the decline of Ming power has been accelerated by such familiar manifestations as corruption in government, popu- lar unrest, ineptness in dealing with external foes, and over-all economic maladjustment indicated by measures to change the tax system. In short, it was an era when the more thoughful educated people were casting about for an explanation of the ills of the times and above all for some far-reaching remedy that might help to avert a dimly sensed impending crisis. The first edition of T’ien-kung k’ai-wu was published only seven years before the Manchu forces toppled the moribund Ming dynasty, and the disturbed times were probably an added impetus goading Sung to undertake the writing of a factual book on the arts and techniques that went into the making of the necessities of daily life, in an attempt to persuade the vast majority of the scholar-officials that these too were matters that merited attention. The author was apparently a close associ- ate of his elder brother Ying-sheng, though their temperaments were obviously different. While Ying-sheng remained the more conventional Confucian scholar-official, who was later to end his own life as a final gesture of loyalty and patriotism, Ying-hsing expressed his concern over the state of the nation through positive use of the knowledge at his command. The note of conviction rings clear in his preface, in which he makes it plain that he was having T’ien-kung k’ai-wu published even though (he adds wryly) this work was not likely to advance any person’s official career. It has often been said that the coming of the Jesuit missionaries to China in the latter part of the Ming dynasty had greatly influenced the intellectual atmosphere of the times, and various works on technology, many of which were translations, are cited as proof of this thesis. While the Jesuits undoubtedly did contribute to the fund of scientific knowledge available in China in the six- teenth and seventeenth centuries, there is little indication in the present work—with the exception of certain items in the chapter on weapons—that they had greatly influenced the writing of Sung Ying-hsing. Seen from the perspective of more than three centuries, it appears that the Jesuits were so Vi TRANSLATORS’ PREFACE readily accepted by the Chinese because the conditions in China were then ripe for the introduction of materialist science, and the late-Ming literati such as Hsii Kuang-ch’i, who collaborated closely with the missionaries in scientific work, reflected the same sort of concern with technological knowledge as did Sung Ying-hsing when he labored over the draft of the present book. Finally, Sung’s home province might have provided much stimulus to his interest in matters industrial and technological. The mid-Yangste province of Kiangsi has been known for centuries for its rich products: rice and other agricultural goods, and above all for its fine porcelain and certain minerals, coal and copper among others. V. K. Ting points out that in Sung’s time natives of Kiangsi often worked as miners in neighboring provinces, and recent research as presented in the Yabuuchi volume shows that Sung Ying-hsing did in fact draw extensively upon the data available in his own province in describing many of the techniques of industry and agriculture. Thus, T’ien-kung k’ai-wu resulted from both the intellectural climate and an immediate local background in late-Ming China. Two editions of T’ien-kung k’ai-wu appeared before 1644, testimony that the book was well received by Sung’s contemporaries. But apparently no new editions were printed during the Ch’ing period, and until recently no copy of the Ming editions had come to light. Various portions of the book, however, were preserved in the eighteenth-century encyclopedia Ku-ching t’u-shu chi-ch’eng, in a compendium on agricultural techniques entitled Shou-shih t'ung-k’ao, and in an early nineteenth-century edition of the Gazetteer of Yunnan Province.* During the eighteenth century, one of the Ming copies was also reprinted in Japan. The current “resurrection” of T’ien-kung k’ai-wu dates from 1914 when V. K. Ting came upon quotations from it in the Gazetteer of Yunnan Province in sections dealing with the metallurgy of copper and silver. The only copy of the book he was able to find, however, was one of the Japanese copies the philologist Lo Chen-yii had brought back to China in the 1880’s. In 1927 after collating the Japanese copy with the portions of the book available in the Ku-chin t'u-shu chi-ch’eng, Mr. T’ao Hsiang reissued the work in China. A 1929 reprint of the T’ao edition included a Supplement by V. K. Ting. In the early 1930’s at least one popular edition appeared, an inexpensive volume published as one of a series of books on Chinese culture designed for use by students.® During the 1950’s interest in this book was kept alive by a Japanese translation (Tenk6é kaibutsu no kenkya—Tokyo, 1953) and critical studies by the seminar of Prof. Yabuuchi and by a reprint in Taiwan, in popular format, of the second T’ao edition. It appears that no one had found any copy of the original book or was aware of the two Ming copies in the Bibliothéque Nation- ale in Paris—one each of the two Ming editions.° Finally in 1959, the Chung-hua Publishing Company of Shanghai re- printed in three attractive volumes the first Ming edition—322 years after its original publication in 1637. According to the publisher’s postface, the original copy had been in the private library of a family named Li in Ningpo, Chekiang, who had recently donated their collection of Chinese books to the National Library of Peking. Vil TRANSLATORS’ PREFACE The appearance of the 1959 reissue helped to clear up an important question: what exactly did the illustrations look like in the original book? The T’ao edition (as explained by V. K. Ting) incorporated many drawings from the Ku-chin t’u-shu chi-ch’eng that were not in the Japanese copy; the added drawings are more ornate and perhaps to some eyes more pleasing, but they add nothing to the technical subjects being illustrated. Moreover, several of the figures in the second chapter (Clothing Materials) are identical with some in another eighteenth century compilation, the imperially commissioned Keng chih t’u or Pictorial Accounts of Agriculture and Sericulture. This variance led us to the conclusion that the “prettier” drawings in the Ta’o editions are in fact not the authentic Ming illustrations. The figures in the 1959 reproduction of the 1637 version, on the other hand, are striking for their simplicity and clarity, as would have been approved, we believe, by an author whose main concern was didactic rather than esthetic. Although retaining those figures from the Ta’o edition that are not in the 1959 copy, we have indicated the source in the captions. In our present effort we are deeply indebted to the many scholars who have published works on the very wide spectrum of subjects treated in this book. We wish to express our special appreciation to Professor Lien-sheng Yang of Harvard University, who not only has given us encouragement and helpful suggestions from the beginning, but has also been good enough to read the present work in manuscript form. We are conscious of the fact that, in spite of our application, many imperfections still remain: for these the translators alone are responsible. E-tu Zen Sun Shiou-Chuan Sun October, 1962 The Pennsylvania State University University Park, Pennsylvania NOTES 1. The first biographical sketch of Sung Ying-hsing written in modern times was by the geologist V. K. Ting (Ting Wen-chiang), who gathered the data from various historical records and published his sketch, along with a critique of the book, in a supplement to the 1929 reissue: T’ien-kung k’ai-wu (in Hsi-yun-hsuan ts’ung-shu, 1929). Viil