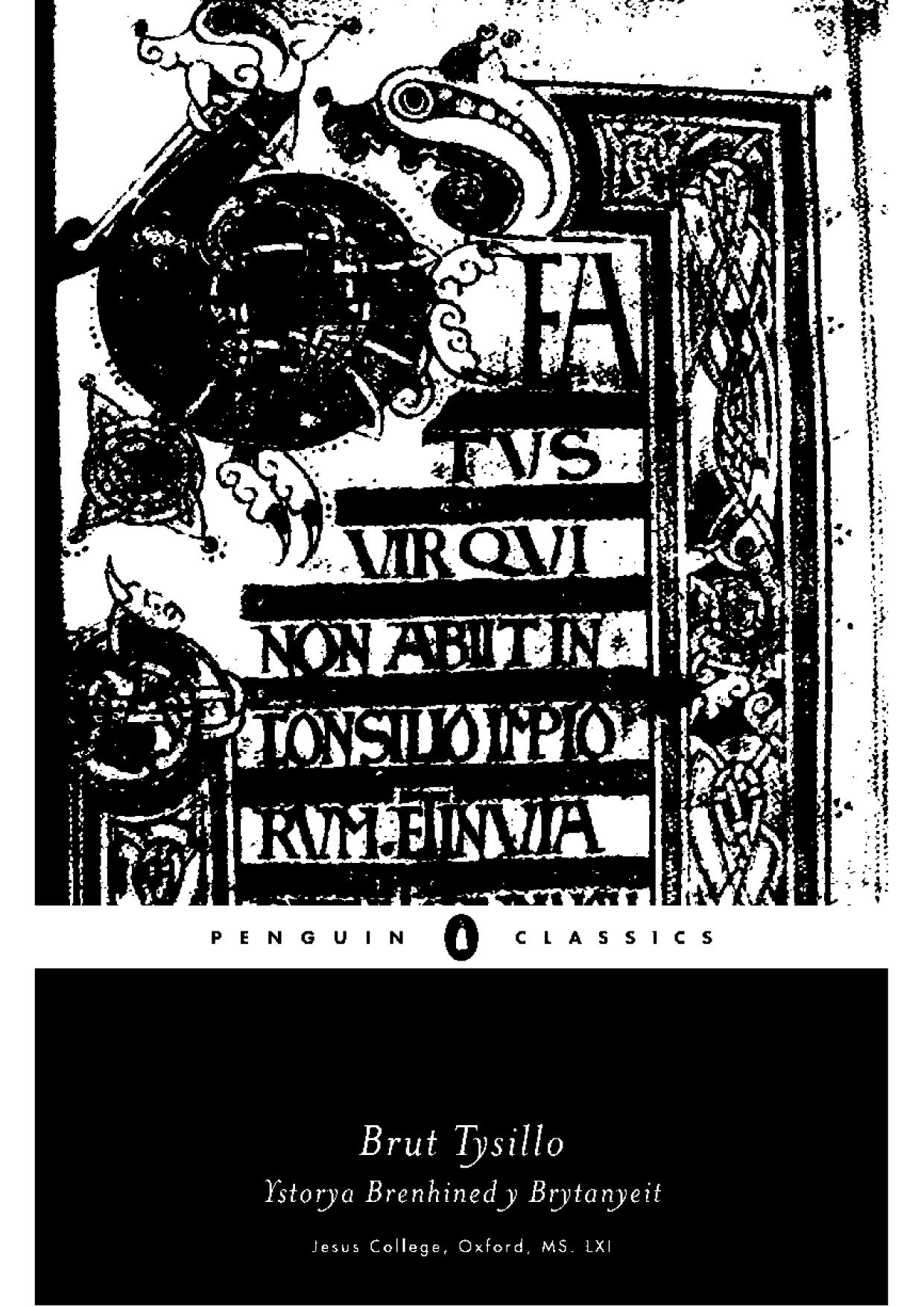

Brut Tysilio, also called the Ystorya Brenhined y Brytanyeit PDF

Preview Brut Tysilio, also called the Ystorya Brenhined y Brytanyeit

‘...Brut Tysilio, a Welsh text which is probably a late reworking of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historiaregum

Britanniae: transcribed from Jesus College MS. 61 by Hugh Jones, Underkeeper of the Ashmolean Museum, in

1695.’, from Jesus College MS. 28 entry in the Bodleian Digital Library, found at

https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/d5ab9ab2-97ce-4379-b2e1-6794b3dd95d5/.

Text from The Celtic Literature Collective, at http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/tysillo.html; Mary

Jones’ Celtic Encyclopaedia serves as an exhaustive and invaluable online hub for Celtic texts and

further study: http://www.maryjones.us/jce/jce_index.html, with the Brut Tysilio page specifically

found at http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/tysillo.html.

An overview of the Brut can be found at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brut_y_Brenhinedd, the

entry for the larger anthological work of which the Brut Tysilio is a version:

The version known as the Brut Tysilio, attributed to the 7th-century Welsh saint Tysilio, became

more widely known when its text was published in The Myvyrian Archaiology of Wales, a once-

influential collection of Welsh literary material whose credibility has suffered due to the involvement

of the antiquarian forger Iolo Morganwg, in 1801–1807. The editors did not place much faith in the

attribution to Tysilio, using that title merely to distinguish it from another Welsh Brut entitled Brut

Gruffudd ap Arthur (the chronicle of Geoffrey son of Arthur, an alternative name for Geoffrey of

Monmouth). An English translation of the Brut Tysilio by Peter Roberts was published in 1811, and

San Marte made a German translation of Roberts' English translation in 1854, making it available

to non-specialists1.

At the very end of the Brut Tysilio there appears a colophon ascribed to Walter, Archdeacon of

Oxford, saying "I […] translated this book from the Welsh into Latin, and in my old age have again

translated it from the Latin into Welsh."2 On this basis, some took the Brut Tysilio to be, at one or

more remove, the "very ancient book" that Geoffrey claimed to have translated from the "British

tongue"3. This claim was taken up by the archaeologist Flinders Petrie, who argued in a paper

presented to the Royal Society in 1917 that the Brut and the Historia Regum Britanniae were both

derived from a hypothetical 10th-century version in Breton and ultimately from material originating

in Roman times, and called for further study.4

However, modern scholarship has established that all surviving Welsh variants are derivative of

Geoffrey rather than the other way around.[14] Roberts has shown the Brut Tysilio to be "an

amalgam of versions", the earlier part deriving from Peniarth 44, and the later part abridged from

Cotton Cleopatra. It survives in manuscripts dating from c. 1500, and Roberts argues that a "textual

study of the version […] shows that this is a late compilation, not different in essentials from other

chronicles which were being composed in the fifteenth century"5.

1.

Françoise Hazel Marie Le Saux, Layamon's Brut: the poem and its sources, Boydell & Brewer Ltd,

1989, pp. 119-120.

2.

Brut Tysilio, tr. P. Roberts, The Chronicle of the kings of Britain. p. 190.

3.

Gerald Morgan, "Welsh Arthurian Literature", in Norris J. Lacy (ed.), A history of Arthurian

scholarship, Boydell & Brewer, 2006, pp. 77-94

4.

Flinders Petrie, "Neglected British History", Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume VIII, pp.

251-278.

5.

Roberts, Brut y Brenhinedd, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1971, pp. xxiv-xxxi

This edition lovingly compiled by Brigantine A. Welsh, to be found at

[email protected] to answer any queries, questions et cetera.