Brunetti's Cookbook PDF

Preview Brunetti's Cookbook

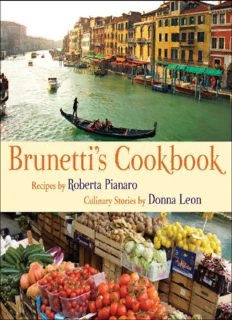

Brunetti’s Cookbook Brunetti’s Cookbook Recipes by Roberta Pianaro Culinary stories by Donna Leon Illustrated by Tatjana Hauptmann Text copyright © 2009 by Roberta Pianaro/Donna Leon and Diogenes Verlag AG Zürich Recipes: English translation copyright © 2009 by Janet Edsforth Stone Illustrations copyright © 2009 by Tatjana Hauptmann and Diogenes Verlag AG Zürich All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or [email protected]. First published as A Taste of Venice: At Table with Brunetti in Great Britain in 2010 by William Heinemann, The Random House Group Limited, London ISBN-13: 978-0-80219710-8 Atlantic Monthly Press an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc. 841 Broadway New York, NY 10003 Distributed by Publishers Group West www.groveatlantic.com *Asterisk in the extracts taken from the Brunetti novels indicates that there is a recipe available for these dishes – refer to the index at the end of the book, or to the detailed table of contents at the beginning of each section. Contents Foreword by Donna Leon: Brunetti a tavola STRADA NUOVA ANTIPASTI • ANTIPASTI ORECCHIETTE CON AMORINI FIRST COURSES • PRIMI PIATTI SANT’ERASMO VEGETABLES • VERDURE CAPITANO ALBERTO FISH AND SEAFOOD • PESCI E FRUTTI DI MARE VOLATILE MEAT • CARNI VON CLAUSEWITZ AT RIALTO DESSERTS • DOLCI INDEX Brunetti a tavola It was never my intention to write a cookbook. After the publication of the fourth Brunetti novel, however, readers began to comment about what they viewed as the conspicuous presence of food and meals in the books. The Brunetti family, sometimes Brunetti alone or in the company of colleagues or friends, ate meals that struck many readers as exceptional in their quality, complexity, and sheer length. At first, this response surprised me, for there had been nothing intentional, nothing precious, about the placement of meals in the books: these novels dealt to a certain degree with family life in Venice, and this was the way that I had, during the last forty years, observed Venetians to eat. Soon it became apparent that such comments came most often, one could say almost exclusively, from readers in countries – how to say this gracefully? – with a culinary culture different from the Italian? (Yes, that sounds sufficiently polite.) Though many Italians have read the books and remarked on them to me over the years, none has ever mentioned the presence of food: for them, as for me, Brunetti’s meals are simply a part of the received culture. How else would people be expected to eat? Certainly, all Venetians, all Italians, do not eat like this all of the time. But I think it is true to say that most of them were raised eating in this manner, and that they still see these long, sensual meals as the normal way to deal with food. It’s not only Venetians who view food in this way: we non-Italians who live here, at least if we live here for any length of time, soon come to regard eating well as a normal part of daily life, worthy of attention but hardly of comment. There is a refreshing lack of self-importance in the way Italians in general think and talk about food: it does not occur to them that their appreciation of food or their interest in it makes them in any way special. This is as normal to them as it is for the British to discuss the weather or for Americans to talk about money. Eating well is not an achievement, a cause for self-promotion and pride: it’s simply something you do twice a day in a manner that will provide as much physical pleasure as possible. One of the first things that was said to me when I came to Italy forty years ago, speaking not a word of the language, was ‘Mangia, mangia, ti fa bene.’ Eat, eat, it’s good for you. At first sound, the command seems to fit into clichéd ideas about Italians: one pictures a heavy-bosomed mother saying it to her numerous children, or the grandmother in some cloying pasta commercial gathering her family under the protective wings of her pappardelle. But, as I was soon to learn, this is nothing more than their recognition of a simple truth: eating is good for you, and eating well is better for you than eating badly. Further, the person who concerns him or herself with feeding you is often doing so out of a desire to keep you well or make you better. In short, it is a manifestation of love, the most simple – if you will, the most primitive – manifestation of love of which we are capable. In the decades I’ve been in Venice, the person who has made that love most manifest is my best, oldest, and dearest friend here, Roberta Pianaro, known to all of us who love her as Biba. It was she and her husband Franco who first opened up this world of food as culture and food as love to me. I’ve been eating at their table and helping in their kitchen for more than thirty years, during which time they have taught me to open not only my mouth and my sense of taste to food, but my mind to it as well. I don’t know how to write a cookbook. I do, however, know how to write about my own experiences with food and cooking and cooks, always seen from the point of view of a person raised in one of those cultures I still don’t know how to describe politely: best perhaps simply to call it a culture with a different attitude to food. After all, with two Irish grandmothers, one grandfather Spanish and the other German, I can hardly present myself as legitimate heir to a rich culinary tradition. Italian life is filled with food: people talk about it constantly, spend a great deal of time shopping for it and preparing it, and devote a joyous amount of time to eating it. One has but to pay close attention to them when they talk about food, or when they cook and eat, to begin to understand how fundamental it is to the living of a happy life and how vital it is to Italian culture. It is the great privilege of my life to have been absorbed, if not into Italy itself, then at least into one Venetian family. Roberta and Franco have, over the years, allowed me to become part of their lives, not only as a guest at their table but as a member, however much a latecomer, of each of their families. When the idea of writing a Brunetti cookbook was first proposed to me I responded in the normal Italian fashion, by turning to my family for help. Whatever I’ve learned about food or how to prepare it I’ve learned during my years spent watching Biba in the kitchen, often sitting at the table and chopping vegetables or asking why something was done in a particular way or in a particular sequence. Though she learned some of the dishes she prepares from cookbooks, most of Biba’s skill stems from being raised within a family that loved to cook and eat, and from having the good fortune to have been born with the culinary equivalent of perfect pitch. Often, when I asked why a certain spice had to be added to a particular dish, Biba could come no closer to an explanation than to say, ‘Because it’s best.’ I would not, and could not, have undertaken this project without her help. Each time we emerged from the kitchen, whether to test and taste what we had made or to share it with friends and the people we love, I was made aware of that fundamental truth that is the animating spirit of Italian cooking: ‘Mangia, mangia, ti fa bene.’

Description: