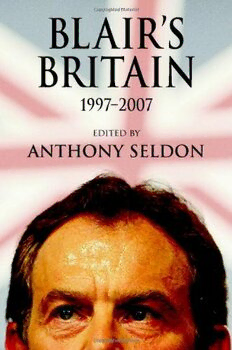

Blair's Britain, 1997-2007 PDF

709 Pages·2007·5.523 MB·English

Most books are stored in the elastic cloud where traffic is expensive. For this reason, we have a limit on daily download.

Preview Blair's Britain, 1997-2007

Description:

This is a useful, if biased, survey of the state of Britain after ten years of Blair's Labour rule. The contributors include a judge, many professors, and the Director of the Royal United Service Institute. One, Professor Lawrence Freedman, wrote Blair's 1999 Chicago speech calling for a more interventionist foreign policy. A third of the book describes how Blair operated, including a piece on his `leadership', but is not useful. However the chapters on the effects of Labour's policies are more revealing.

Our manufacturing industry gets just 15 pages. Investment as a share of GDP was lower in 2003-5 than it had been in 1976-8. The National Institute for Economic and Social Research reported in 2005 that there had been 'no obvious improvement' in productivity since 1997. Investment in R&D has lagged behind France, Germany and the USA, and was actually lower in 2004 as a percentage of GDP than in 1995.

In 2006, a third of working-age adults still lacked any recognised skills. The scandal of poverty was scarcely lessened: the Low Pay Unit reported that two million children were working illegally, mostly the children of immigrants. A Bill to make it harder for gang masters to exploit foreign labour fell through lack of support.

Globalisation increases inequalities within and between nations and the Labour Party `embraced global capitalism with enthusiasm', as Robert Taylor notes. In 1997, the richest thousand owned £98.99 billion; in 2007, £359,943 billion, up 263%. The International Monetary Fund pointed out that Britain was as attractive to foreign capital as the Cayman Islands, a tax haven. Peter Sinclair concludes that Labour's "greatest achievement was to consolidate the revolution of their Conservative predecessors."

Philip Stephens of the Financial Times writes of the `unprecedented investment in health and education', but doesn't ask how much went straight through to private companies, via Private Finance Initiatives and Public Private Partnerships. Blair claimed that PFIs and PPPs would end the need for public investment in those areas - which was, as Stephen Glaister comments, `plainly nonsense'. Sinclair notes the PFIs' `legacy of financial poison for the health trusts that had been induced to enter them'. By 2010, the NHS will be paying £2 billion to cover the charges the annual charges on PFI schemes. Brown forced the biggest ever PPP scheme on the London Underground, which has been a disaster.

Tim Newburn and Robert Reiner note that Canada, Scotland, Belgium, Germany and Japan all achieved crime drops without imprisonment increases. They deplore the government's `increasingly ruthless and shrill attacks on civil liberties'.

Target-setting in education and the stress on diversity of schools were misguided, resulting in a free-for-all (including the nonsense of faith schools, not mentioned in the book). UNICEF's 2007 report on child well-being found us 21st out of 21 `developed' countries.

Timothy Garton Ash writes, "the invasion and occupation of Iraq has proved to be a disaster ... the most comprehensive British foreign policy disaster since the Suez crisis of 1956." In a March 2007 poll, majorities supported the immediate withdrawal of British troops from Iraq and Afghanistan. Two-thirds thought that Britain was over-extended and that it should not "become involved in any foreign conflict unless it is absolutely clear that it is in Britain's own interest to do so."

The editor, Anthony Seldon, Master of Wellington College, sees as `successes' what most of us see as disasters - the city academies, competition in the NHS, privatisations, PFI and keeping Thatcher's anti-trade union laws. This is a smug, establishment view. Labour under Blair continued Thatcher's destruction of Britain, and Brown continues it now.

See more

The list of books you might like

Most books are stored in the elastic cloud where traffic is expensive. For this reason, we have a limit on daily download.