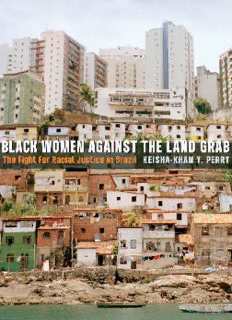

Black Women against the Land Grab: The Fight for Racial Justice in Brazil PDF

Preview Black Women against the Land Grab: The Fight for Racial Justice in Brazil

Black Women against the Land Grab This page intentionally left blank BBLLAACCKK WWOOMMEENN AAGGAAIINNSSTT TTHHEE LLAANNDD GGRRAABB The Fight for Racial Justice in Brazil KEISHA-KHAN Y. PERRY University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis | London Portions of chapter 1 and chapter 3 were previously published as “The Black Movement’s ‘Foot Soldiers’: Grassroots Feminism and Neighborhood Struggles in Brazil,” in Comparative Per- spectives on Afro-Latin America, edited by Kwame Dixon and John Burdick, 219–40 (Gaines- ville: University Press of Florida, 2012); reprinted with permission of the University Press of Florida. Portions of chapter 3 and chapter 6 were previously published as “Politics Is uma Coi- sinha de Mulher (a Woman’s Thing),” in Latin American Social Movements in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Richard Stahler-Sholk, Harry E. Vanden, and Glen David Kuecker, 197–211 (Lanham, Md.: Rowman and Littlefield, 2008). Portions of chapter 3 were previously pub- lished as “Social Memory and Black Resistance: Black Women and Neighborhood Struggles in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil,” Latin Americanist 49, no. 1 (September 2005): 811–31, and as “The Roots of Black Resistance: Race, Gender, and the Struggle for Urban Land Rights in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil,” Social Identities 10, no. 6 (2004): 7–38. Portions of chapter 6 were previously published as “‘If We Didn’t Have Water’: Black Women’s Struggle for Urban Land Rights in Brazil,” Environmental Justice 2, no. 1 (March 2009): 9–14. Excerpt from the Gamboa de Baixo neighborhood political hymn republished with permis- sion of Ana Cristina da Silva Caminha. Excerpt from “o muro” by Oliveira Silveira republished with permission of Naira Rodrigues Silveira. Excerpt from Medea Benjamin and Maisa Men- donça, Benedita da Silva: An Afro-Brazilian Woman’s Story of Politics and Love (Oakland, Calif.: Food First Books, 1997); republished with permission. Copyright 2013 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, record- ing, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perry, Keisha-Khan Y. Black women against the land grab : the fight for racial justice in Brazil / Keisha Khan Y. Perry. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8166-8323-9 (hc) ISBN 978-0-8166-8324-6 (pb) 1. Women, Black—Political activity—Brazil—Salvador. 2. Urban poor—Political activity— Brazil—Salvador. 3. Blacks—Brazil—Salvador—Social conditions. 4. Urban renewal— Brazil—Salvador. 5. Salvador (Brazil)—Politics and government. I. Title. HQ1236.5.B6P47 2013 305.896'081—dc23 2013029575 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii INTRODUCTION Diasporic Blackness and Afro-Brazilian Agency xi 1. Engendering the Grassroots 1 2. The Gendered Racial Logic of Spatial Exclusion 27 3. The Black Movement’s Foot Soldiers 55 4. Violent Policing and Disposing of Urban Landscapes 87 5. “Picking Up the Pieces”: Everyday Violence and Community 117 6. Politics Is a Women’s Thing 139 CONCLUSION Above the Asphalt: From the Margins to the Center of Black Diaspora Politics 169 References 179 Index 197 This page intentionally left blank ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In some ways the inspiration for this book began when I took Kim Hall’s Introduction to Women’s Studies at Georgetown University as an undergraduate. I express heartfelt gratitude to her. She ignited my initial interest in black women’s thought and political practice, intro- ducing me to the scholarship of Patricia Hill Collins, Audre Lorde, Barbara Smith, and many other black feminist theorists who have in- fluenced my personal politics and the framing of this book. Over the years she has contributed her time by reading my work, applauding as well as critiquing, and giving me crucial advice on how to be a serious scholar and survive the academy. As the saying goes, it takes a village to raise a child. A village, led by the village chief herself, my mother, Joy Anderson, has nurtured my aspirations as an academic and my intellectual desires. She raised me to be strong like her and the other women in our family. She has taught, by example, how to persevere in the never-ending pursuit of knowledge. She has raised my brothers, “teen prodigy” Kofi and “ar- tiste extraordinaire” Emeka, to shower me with an abundance of love. I also thank my father, Paul Perry, for instilling in me the meaning of a proverb popular in Jamaica: “Labor for learning before you grow old, for learning is better than silver or gold. Silver and gold will vanish away, but a good education will never decay.” Without Ana Cristina, one of the most important leaders of the housing and land rights struggle in Salvador da Bahia, Brazil, the re- search for this book could not have been completed. Ana Cristina’s assistance was priceless. The level of her political commitment to col- lective social change and the breadth of her political influence in Sal- vador’s grassroots networks are remarkable. I would be an exceptional woman, activist, and scholar if I had only a spoonful of her courage. Because of her, I decided to name the neighborhood and the activists in this book rather than leaving them anonymous. I thank the members vii viii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS of the Gamboa de Baixo neighborhood association who welcomed me into their homes and hearts: Rita, Angela, Adriano, Lu, Lia, Boa Morte, Nice, Lula, Joelma, Dona Iraci, Dona Lenilda, Dona Detinha, Dona Marinalva, Ivani, and Maria José. I hope I have adequately told the stories of their struggle to maintain peace in their community and the city of Salvador. Special thanks go to Ritinha and my friends Simone, Nicelia, and Luciana, who continue to ensure my trips to Salvador are filled with good food, conversation, and laughter. I am also beholden to Elizete da Silva, João Rocha, and Elizete’s niece Janmile Cerqueira, who have been a constant source of encourage- ment over the years. I am grateful for the friendship of Lazaro Cunha and his family (Silvio, Ana Paula, Dona Silvia, and Marcia), who have been good to me and the many other diasporic visitors I sent to them. Ari Lima, Sales Augusto dos Santos, Vilma Reis, Isabelle Pereira, and Lisa Earl Castillo have been great friends and colleagues in Brazil, and their scholarship and intellectual exchanges shaped and benefited this work. This book would not have been possible without the intellectual and personal support of the following people at the University of Texas at Austin: Edmund T. Gordon, for his consistent generosity and in- tellectual insights over more than a decade; Asale Angel-Ajani, who deeply influenced my decision to foreground black women’s voices; João Costa Vargas, who guided the development of my ideas on urban space and politics; and Charlie Hale and Angela Gilliam, who encour- aged me to think of Brazilians’ material reality as not so different from those of black people globally. I thank Paula V. Saunders, my closest friend and colleague while at the University of Texas at Austin. She diligently read every page of my dissertation and taught me the true meaning of friendship and sisterhood. I credit Sônia Beatriz dos Santos with broadening my thinking about Afro-Brazilian women and black Brazilian feminist thought. Jennifer, Lisa, Miguel, Amanda, and the late Vincent Woodard gave me the necessary community space to thrive as a scholar. Kahlil Hart, the older brother we all should have, introduced me to the diverse Caribbean community in Austin that offered a necessary respite from campus life. I am grateful for his friendship and profoundly appreciate his willingness to try to “reason” with me. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ix Christen Smith, Erica Williams, Cheryl Sterling, Kim Butler, and Kia Lilly Caldwell are African American Brazilianist scholars who have shared the journey of conducting research in Salvador. Trimiko Mel- ancon, Carol Bailey, and Jonathan Fenderson have supported me in completing this book and in being successful as a young teacher and scholar. Lamonte Aidoo, Ebony Bridgewell-Mitchell, Edizon León, Michelle McKenzie, Lindah Mhando, Karen Flynn, Kamille Gentles- Peart, Luis Ramos, Jermain McCalpin, Silvia Rodrigues, and Robyn Spencer have been wonderful friends who have counseled me through the rough times and helped me move forward. This project has been supported by numerous research grants and fellowships: the National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship, the NSF Dissertation Improvement Grant, the J. William Fulbright Foreign Scholarship (Brazil), the Mendenhall Dissertation Fellowship, the Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow- ship at Smith College, and the Africana Research Center Postdoctoral Fellowship at Pennsylvania State University. I have received funding from the African and African American Studies Center, the Center for Latin American Studies, and the Department of Anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin and from the Africana Studies De- partment, the Humanities Fund, the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, the Faculty Development Fund, and the Office of International Affairs at Brown University. I thank my colleagues in the Africana Studies Department at Brown University: Anani Dzidzienyo, who read every page of the manuscript draft and offered keen insights; Corey D. B. Walker, who has been cru- cial in my understanding of theoretical contributions to black political thought and Africana women’s studies; Deborah Bowen, a cherished friend; and all of my colleagues (Chinua Achebe, Geri Augusto, Karen Baxter, Anthony Bogues, Lundy Braun, Matthew Guterl, Françoise Hamlin, Paget Henry, Alonzo Jones, Michael Ruo, Tricia Rose, Ruth Simmons, Elmo Terry-Morgan, and John Edgar Wideman), who deeply inspired this work. It is hard to imagine my dear sister, Dr. Aaronette White, is not here to share this important achievement with me. This book is just one small example of Aaronette’s enormous influence dur- ing her short life. Special thanks go to Margaret Copeley, Rhoda Flaxman, and Tatiana

Description: