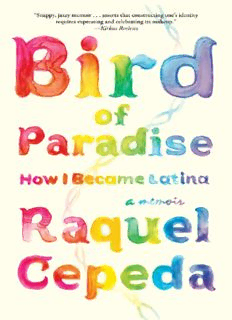

Bird of Paradise: How I Became Latina PDF

Preview Bird of Paradise: How I Became Latina

Thank you for downloading this Atria Books eBook. Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Atria Books and Simon & Schuster. CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP or visit us online to sign up at eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com CONTENTS Author’s Note Preface Part I CHAPTER 1: Love, American-Style CHAPTER 2: Mean Streets CHAPTER 3: Journey into the Heart of Darkness CHAPTER 4: Uptown ’81 CHAPTER 5: An Awakening CHAPTER 6: Jesus Christ and the Freakazoid CHAPTER 7: Ave Maria, Morena CHAPTER 8: God Bodies and Indios CHAPTER 9: There’s No Other Place . . . CHAPTER 10: Whitewash Part II CHAPTER 11: Truth, Reconciliation, and Time Machines CHAPTER 12: Things Come Together CHAPTER 13: Tripping in Morocco CHAPTER 14: Running the Fukú Down CHAPTER 15: Flash of the Spirit CHAPTER 16: She Who Walks Behind Me CHAPTER 17: Paradise Gone CHAPTER 18: Becoming Latina Postscript Acknowledgments Ancestral DNA Testing: Now It’s Your Turn Frequently Asked Questions DNA Test Kit Instructions Selected Sources and Further Reading About Raquel Cepeda Index Family Tree DNA Discount Coupon Because of Djali and Marceau . . . For my little sisters at Life is Precious: you are loved. Always in your stomach and skin there was a sort of protest, a feeling that you had been cheated of something that you had a right to. It was true that he had no memories of anything greatly different. . . . Why should one feel it to be intolerable unless one had some kind of ancestral memory that things had once been different? —GEORGE ORWELL, 1984 As all historians know, the past is a great darkness, and filled with echoes. Voices may reach us from it; but what they say to us is imbued with the obscurity of the matrix out of which they come; and try as we may, we cannot always decipher them precisely in the clearer light of our day. —MARGARET ATWOOD, THE HANDMAID’S TALE AUTHOR’S NOTE The events in this book are all true. My word is bond. The story of the car wreck that was my parents’ relationship was constructed by interviewing the two of them and other family members. The story about the Indian couple in Chapter 1 was one of the few incidents that both of my parents recounted with no bias or variation. Some of the sequences have been rearranged, and in most cases, I changed the names and certain identifying details to protect the innocent and the guilty. Doña Amparo is a composite of a few elderly women in the ’hood. On another note, I capitalized the word “Black”—as I would, say, African- American—throughout the book. I believe that “Black” is used interchangeably, like “Hispanic” and “Latino/a” are, as an identifier for a larger ethnic group bound by their shared transatlantic experience with slavery. I don’t think the same is true when it comes to whiteness. I also use the term Native and Indigenous American interchangeably, preferring the latter but using the former sometimes so as not to confuse readers. Last, I prefer to use “Latino” and “Latina” over “Hispanic,” although I don’t find the latter offensive. I personally identify as a Latina when I’m in the company of other Americans, a Dominican-American when I’m in the Dominican Republic or here, in the company of other folks whose parentage hails from Latin America. And sometimes I identify as a pura dominicana when I’m in my ’hood. PREFACE Who in the world am I? Ah, that’s the great puzzle. —LEWIS CARROLL, ALICE IN WONDERLAND AS I WRITE THIS, MY THREE-MONTH-OLD SON IS STARING AT ME intensely from his bouncy seat. He’s cooing loudly, like he’s trying to tell me something important, something he’ll forget by the time he utters his first word. Marceau has been here before. Of this, I am sure. The left half of our brains, programmed to think that seeing is believing, would dismiss this kind of thinking as esoteric new age bullshit. However, there’s the other half that can’t dismiss the idea that there just might be something to it. Many of us have recognized old souls in babies and children. We’ve felt the presence of some force, be it a spiritual guide or God, intervening in our lives at some point. When I look over at my son in his bouncer, I’m reminded of what a rabbi in Brooklyn, a seer in Fez, and a santero in Queens told me with slight variation when I was writing this book. We travel with the same clan over and over again, from one life into the next, until some ultimate purpose is fulfilled and we no longer need to return. When we illuminate the road back to our ancestors, they have a way of reaching out, of manifesting themselves . . . sometimes even physically. Last year I embarked on an archaeological dig of sorts, using the science of ancestral DNA testing to excavate as many parts of my genetic history as I could in the span of twelve months. The DNA kits I collected were processed by Family Tree DNA, a Houston-based commercial genetic genealogy company. The company’s founder and CEO, Bennett Greenspan, provided further analysis. I tested myself, my father, a paternal great-uncle I hadn’t met until the beginning of my project, and a maternal cousin I found on Facebook. I wanted to learn as much as I could about my ancestors’ origins before we became Latino. I’ve always been intrigued by the concept of race, especially in my own community and immediate family, where it’s been a source of contention for as long as I can remember. The United States has the second highest Latino population in the world, second only to Mexico. And still, the media—they lump us all together into one generic clod—doesn’t get us, either. Are Latino- Americans white? Black? Other? Illegal aliens from Mars? Or are we the very face of America? Some see Latinos as the embodiment of this young country’s cultural melting pot. And though Mexicans have been residing here since before the arrival of the first Europeans, many of our fellow Americans view Latinos as public enemies. What our parents see isn’t necessarily what we first-and second-generation American-born Latinos see when looking at ourselves in the mirror. According to the 2010 census, over half of all Latinos here identified as being solely white, and about a third checked “Some Other Race.” I was one of the three million, or 6 percent, who reported being of multiple races. I guess it all depends on whom you ask and when you ask. Race, I’ve learned, is in the eye of the beholder. I don’t look all the way white or all the way Black; I look like someone who’s a bit of both and then some—an Other. In Europe, people have mistaken me for Andalusian, Turkish, Brazilian, and North African. In North and West Africa, I’ve been asked if I’m of Arabic or Amazigh descent. In New York, Los Angeles, and Miami, it varies: Israeli or Sephardic, Palestinian, Moroccan, biracial Black and white American, Brazilian, and so on. I’ve been mistaken for being everything except what I am: Dominican. My own racial ambiguity has been a topic of conversation since I was a teenager. Blending in has filled the pages in my book of life with misadventures and the kind of culturally enriching experiences that make me feel, truly, like a world citizen. In more recent times, I found the idea that we live in a so-called post-racial society downright fascinating. I suspect someone at the White House or Disney created that catchphrase after the election of President Barack Obama, to fool us into thinking we’re now living in a parallel universe where race is suddenly a nonfactor. The term “post-racial” is an epic failure. More than four years after the fact, our first Black president’s skin tone is still getting people punch-drunk with hate. It has fueled the dramatic rise in hate groups and the revival of the so- called Patriot movement. Sure, our sucky-ass economy factors in to the foaming- at-the-mouth vitriol against President Obama, but there’s something else contributing to the mainstream’s arrogant contempt for him. As intangible and trivial as our differences are, we cannot pretend that race doesn’t matter anymore. The exploration of and how we choose to identify ourselves is something else that compelled me to set upon this journey. Our identities are as fluid as our

Description: