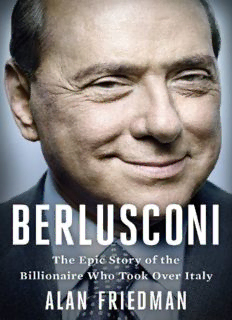

Berlusconi: The Epic Story of the Billionaire Who Took Over Italy PDF

Preview Berlusconi: The Epic Story of the Billionaire Who Took Over Italy

Begin Reading Table of Contents Photos Newsletters Copyright Page In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. For Gabriella AUTHOR’S NOTE As an American journalist who grew up in the 1970s, I have always been fascinated by the Frost-Nixon interviews, that famous series of face-to-face television interviews which British journalist David Frost conducted with President Richard Nixon in the spring of 1977, more than two years after Nixon’s dramatic resignation. I was obsessed by Watergate, even as a teenager, the way kids today are obsessed by video games and Facebook. The drama. The intrigue. The White House tapes. The cover-up. The Washington Post scoops by reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. The humbling of the president of the United States of America! The famous statement by Nixon that “people have got to know whether or not their president is a crook. Well, I am not a crook.” I couldn’t get enough of it. I craved the next installment in the Watergate saga. I consumed it like candy. In the summer of 1974, at our summer house on a lake in upstate New York, I forced my thirteen-year-old sister to join me in watching the daily TV coverage of the impeachment hearings, which culminated in August in the dramatic resignation of President Richard Nixon. We watched him resign and then we watched him say good-bye to the White House staff, with that bizarre salute, that wave of despair he offered to the American people before boarding his helicopter on the White House lawn in order to fly to Andrews Air Force Base and then begin the long flight back to California, in disgrace. All of these memories came flooding back in early 2014 when my Italian publisher at Rizzoli in Milan first suggested I try to get Silvio Berlusconi, the most colorful and controversial leader in modern Italian political history, to agree to tell me his life story. I had known Berlusconi for thirty years, from my early days as a foreign correspondent in Milan for the Financial Times of London in the 1980s. At times I had been a fierce critic of Berlusconi, then later I became intrigued by his personal story. This was not only because of his alleged “bunga-bunga” parties and the corruption trials but because of the extraordinary, epic-like story of his life. I followed closely the events surrounding his political downfall in 2011, his conviction in 2013 on tax fraud by Italy’s Supreme Court, and his eviction from the Italian senate later that year. Yet even today Berlusconi still casts a long shadow in Italy, so I remained curious about the story. When I first went to ask him if he was interested in cooperating on this book, I had low expectations. It was late on the morning of March 12, 2014. I went to see him at his ornate residence in Rome, the second floor of a seventeenth- century palazzo, resplendent with frescoed ceilings and gold tapestry-covered walls. Berlusconi, now seventy-seven years old, seemed to like me, mainly because I was an American (and therefore not an Italian journalist with preconceived notions) but also because he felt vindicated by another book I had written about Italian politics, a result that had not been my aim in life. I informed Berlusconi that I had decided to write a book about his life story and I proposed that he provide me with full cooperation and unfettered access to archives, family members, friends, business partners, and political allies. He first gave me a long stare in the eye, then told me that over the past decade he had refused at least fifteen similar requests. I told him this would not just be a book but also a series of ten or fifteen television interviews, modeled on the famous Frost-Nixon interviews of 1977. He kept staring at me, muttered something about understanding that today “everything needs to be multimedia,” and then suddenly he proffered his hand. We shook hands, and he was very clear in what he then said: “I trust you to tell my story in a fair and honest way.” I thanked him for his confidence and informed him directly: “This will not be hagiography. I will not write the story of a saint, or of a victim, I will not be hostile but I will not do you any favors. I will write in a fair and balanced way the story of an extraordinary life, as I see it, but with you answering my questions about each chapter of your life, and all of it taped on video.” Silvio Berlusconi agreed to my terms. Later that day one of his advisers shared his opinion as to why Berlusconi had said yes: “His world is collapsing around him, and while he dreams of making another political comeback, he sees this as his legacy, with you as his witness, as the first and last journalist with whom he will share his life story, in his own words.” In the seventeen months that followed, from the tumultuous spring of 2014 until the end of the summer of 2015, I observed Berlusconi up close, mainly at home. We had numerous conversations and interviews during a period full of emotion for Berlusconi, a period marked by a fair amount of bitterness and defeat and at the same time a period of constant planning for a political comeback. In some ways I watched a real-life psychodrama playing out before my eyes. I was also privileged by the unusually free access, which allowed me to really get to know the man, and his default mechanisms, his thought patterns, his pet peeves, even his favorite anecdotes and jokes. For a while, each time I went to interview him, whether at the palazzo in Rome or in the garden of his spectacular villa in the village of Arcore, on the outskirts of Milan, something bad was happening. He was emotional at times, usually in the run-up to another court ruling in one of his many cases. Often, after the interviews, he would ask me to speak in private, and he would pour out his heart, speak of his enemies, or confide in me his concerns, his hopes, his ambitions. I always told Berlusconi that my model was the Frost-Nixon interviews. I said it on many occasions. I said it when he signed the release forms for this book and for the TV series in front of me and three other witnesses, including his girlfriend, Francesca Pascale, and his spokesperson, Deborah Bergamini. When he signed the legal authorization documents, the release forms that were needed to proceed with the project, for some reason I was reminded of the most famous words uttered by President Nixon to David Frost in those legendary interviews: “I brought myself down. I gave them the sword and they stuck it in, and they twisted it with relish…” I wondered what Silvio Berlusconi would say about his own part in his incredible and epic journey. As the weeks and months progressed, I would not be disappointed. Lucca, Tuscany August 26, 2015 PROLOGUE S ilvio Berlusconi is at home alone. He is strolling through a garden in the middle of his 180-acre property, not far from the stables and the helipad. It is high summer and he is proceeding, hands in his pockets, along a tree- lined path that leads to his eighteenth-century seventy-room villa. As we approach the huge mansion, the borders of the walkway are lined with closely cropped hedges and terra-cotta pots full of geraniums. The grassy avenue passes beneath a stone arch and then gives way to sprawling gardens, manicured lawns, beds of red azaleas, lemon trees, and hedges, all immaculate. Not far from his house, the seventy-eight-year-old billionaire pauses. He smiles, almost a trifle sheepishly, with the self-deprecating charm and courtesy that tends to disarm his guests, especially those expecting to meet a flamboyant playboy. He smiles broadly, with the empathy that helped him to rise to power, and which over the past twenty-five years allowed him to transform himself from a media mogul into one of the world’s richest men into the longest-serving and undoubtedly the most controversial prime minister of Italy. “This,” says Berlusconi, “is the main home in my life.” Despite the warm weather, Berlusconi is wearing a light black sweater, a navy blue blazer, and cotton tracksuit trousers. The gravel crunches under his black Hogan sneaker-boots as he marches forward, talking about the importance of this property to him, describing it as the place where he has made all of the momentous decisions in his life. Neoclassical statues on marble pedestals are visible as far as the eye can see, and they seem to stare across the walls of the gardens, which are almost too perfect. The big old villa is located in the Milanese countryside in a Lombardy village called Arcore. It is called the Villa San Martino and it was built in the early 1700s on the foundation of what had been, from the twelfth century onward, a Benedictine monastery. Berlusconi bought it in the 1970s and refurbished it in grand style. He kitted it out with more gadgets than a James Bond movie, plus a stable packed with racehorses, a helipad for his chopper, and even a private soccer field. The house is tastefully appointed, if a bit long on tapestries and Old Masters. Every corner is a potpourri of old and new, with a 1980s aesthetic that at the time allowed Italy’s rising class of nouveau billionaires to juxtapose even Renaissance paintings with Late Modern. As a result, in the 1980s many architects and interior decorators in the Milan area became quite rich, quite quickly. Berlusconi is strolling toward the big house now, relaxed and proud, believing that the finest appreciation of a great Italian villa often begins outside, with its landscape. “This is the main home in my life,” he repeats. And life, for Berlusconi, always means both the public and the private, and often the two flow into each other, overlapping in a manner that sometimes causes scandals, but which somehow always involves a return to this villa. Now Berlusconi is speaking of the first visit here by Mikhail Gorbachev in 1993, and of the long afternoon and evening they spent together. “It was a very enjoyable, stimulating day together,” Berlusconi recalls. “Mikhail Gorbachev came with his wife, Raisa, and she spent time with my wife, Veronica. He wanted to meet with an Italian business leader and talk about the economy. He asked me many questions, about the economy and about financial markets. At five in the afternoon we sat down for some tea, and then he was scheduled to leave. As we were walking to the door to say good-bye, he said to me, ‘But, Silvio, there is one thing I did not understand. Which is the ministry or the institution which fixes the prices for the products that are sold?’ “I asked him to repeat the question. He did. ‘Which institution determines prices?’ And I said, ‘Mikhail, please don’t go. Stay for dinner. We need to talk more.’ We talked and talked, with the help of a few glasses of really good Rosso di Montepulciano. I explained how in the West it is the market which determines prices, and not a government agency. It is market competition. It was incredibly gratifying to explain the workings of market capitalism to Mikhail Gorbachev. At least he seemed to appreciate the time we spent together.” Now Berlusconi is describing the visits to Arcore by his friend Vladimir Putin, pointing out the room that Putin slept in when he last came to stay. Arcore. In the life of Silvio Berlusconi this Italian villa is far more than just the site of visits by Mikhail Gorbachev and Vladimir Putin. It is his residence, his refuge, his command center, his general headquarters. It was here that he planned and built his real estate empire, the satellite cities that helped make him a billionaire. It was here that he made decisions that would see him morph into a media mogul, with a television empire spanning half of Europe. It was here that he invented commercial television in Italy and became a first mover across the European stage in the 1980s. It was here, in these dainty and somehow overly pristine drawing rooms, dining rooms, and baroque salons that Berlusconi decided to buy the AC Milan soccer team. It was here that he first decided to go into politics, to invent and launch a new national party, and to go from being a rich businessman to gaining the prime minister’s office in less than ninety days in early 1994. Arcore became an Italian version of Camp David. In later years, it also became a bunker, where Berlusconi would hold endless late-night sessions with defense lawyers, batteries of attorneys and investigators, and armies of advisers who helped him face a storm of more than sixty separate indictments and trials on corruption, bribery, tax fraud, and even underage prostitution charges. Arcore was Berlusconi’s Rosebud, his compass, his touchstone. In life, in business, in politics, and in questions of love and family. It was here in Arcore that Berlusconi’s first marriage ended, it was here that the alleged bunga-bunga parties took place, it was here that he lived for a year in a semi-curfew and semi- imprisonment, his passport confiscated by the courts, doing community service in a home for elderly Alzheimer’s patients after being convicted of tax fraud. And it was here that he plotted his latest political comeback in 2015. It was here in the family chapel that he interred the ashes of his parents and of his sister. It was here that his son and daughter-in-law and grandchildren still lived. It was here that at the age of seventy-six he took a new girlfriend, some fifty years his junior. It all happened here. At Arcore. I am reminded of the very first time I went to see Berlusconi at Arcore, back in the 1980s when Tina Brown asked me to write a piece for Vanity Fair about the “New Princes” of Italian capitalism who were challenging the “Uncrowned King of Italy,” Gianni Agnelli. It was the wild and crazy 1980s, with half of the world drunk on a golden age of newfound prosperity, from the yuppie classes of Wall Street to the money men of the City of London in constant celebration mode, with booming economies and a rising middle class. Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher ruled America and Britain. In Italy in the 1980s, Berlusconi was a self-made man, an outsider, a fast-rising tycoon, an entertainment industry and TV mogul, a newly minted billionaire, on his way to becoming one of the world’s richest men. Back then Berlusconi caused a particular discomfort among the financial elites of Italy because his folksy style of salesmanship had made

Description: