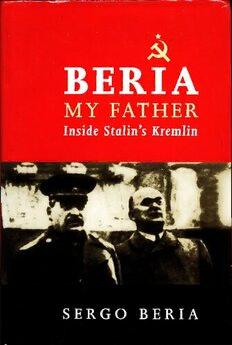

Beria, My Father: Inside Stalin's Kremlin PDF

Preview Beria, My Father: Inside Stalin's Kremlin

BERIA MY FATHER Inside Stalin’s Kremlin SERGO BERIA Beria, My Father Inside Stalin’s Kremlin Sergo Beria Despite the steady declassification of secret archives, Stalin’s Kremlin has remained riddled with questions. What justified the ceaseless bloodshed? How did the megalomaniac Georgian maintain his power? Was Stalin about to unleash World War III? In this controversial memoir, Sergo Beria, son of the man Stalin called ‘Our Himmler’, at last offers a vivid eye-witness account of life at the heart of the ‘Evil Empire’. Lavrenti Beria, easily the most shadowy character of the Politburo, stands at the heart of his son’s tale. Arrogant, given to tempestuous moods and an insatiable libido, he was feared as a sadistic spymaster who prowled Moscow’s wind-swept avenues for women in his blacked-out Volga. Yet at home he played the family man who commanded the respect of his wife and child. This book chronicles Beria’s increasing hatred of Stalin, a fellow Georgian, and the sweeping anti-Stalinist reforms which he pushed through after Stalin’s death. In addition to vivid portraits of Stalin and his father, Sergo Beria’s story includes many details of the claustrophobic atmosphere surrounding the nomenklatura, his pursuit by Stalin’s daughter Svedana, and the fall of his father at the hands of the amiable Khrushchev - who had Beria arrested and shot. Contrasting sharply with Svedana’s and Khrushchevas accounts, this gripping book offers proof why, even today, Russia is unable to untangle its twisted past. Lavrenti Berta and his son Sergo Beria was born in Georgia on 28 November 1924. Stalin - friendly with his mother - frequently visited the Beria household, as did Stalin’s daughter Svetlana. Arrested after the execution of his father, he was released a year and a half later from his confinement. Banned from Moscow and forced to change his name, he continued to work for Khrushchev as an engineer on missiles while his wife, a granddaughter of Gorki, and children remained in Moscow. Framjoise Thom is a specialist in Communist history of the period and teaches at the Sorbonne. A large part of the book is based on interviews she had with the author. Her notes provide a comprehensive commentary on his testimony and are based on exhaustive research of existing and declassified archives. Brian Pearce taught English to Russian Embassy staff in the 1950s and was in Russia at the time of Lavrenti Beria’s fall. He is one of Britain’s most experienced translators of Communist history. He has translated over forty books from French and Russian. Beria, My Father Inside Stalin’s Kremlin SERGO BERIA Edited by Frangoise Thom English translation by Brian Pearce Duckworth First published in 2001 by Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd. 61 Frith Street, London W1D 3JL Tel: 020 7434 4242 Fax: 020 7434 4420 Email: [email protected] www. ducknet. co .uk © 1999 Sergo Beria © Editorial notes and comment 1999/2001 Frangoise Thom © Translation 2001 Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd The moral right of Sergo Beria to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance With the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The right of Brian Pearce to be identified as the translator of this Work has been asserted in accordance with Sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Originally published as BERIA mon pere © Plon/Criterion, Paris, France, 1999. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 7156 3062 8 Typeset by Derek Doyle and Associates, Liverpool Printed in Great Britain by Bookcraft (Bath) Ltd, Midsomer Norton, Avon Contents Editor’s Preface Franqoi.se Thom vii Editor’s Note Franqoise Thom xi 1. In Stalin’s Shadow 1 2. The NKVD 33 3. Hitler 47 4. War 69 5. ‘Peace’ 103 6. Stalin 133 7. The People around Stalin: 150 8. The Bomb 172 9. Disillusionment 195 10. Stalin’s Grand Design 223 11. The first de-Stalinisation 251 12. Fall 268 13. Who Was My Father? 279 Author’s Epilogue Sergo Beria 297 Appendix 299 Notes 302 Bibliography and Sources Used for the Notes 374 Biographical Notes 379 Index of Names 386 Index of Places 394 Editor’s Preface After the collapse of Communism and the partial opening of the Soviet archives, historians of the USSR and of Communism enjoyed a period of euphoria. At last we were going to learn what had gone on in the entrails of the sphinx, the jealously-guarded secrets of the Kremlin were to be exposed to the gaze of outsiders ... These expectations were fulfilled only in part. The Soviet archives made available were, in fact, far more eloquent concerning the peripheral mechanisms of the regime and on the working of the bureaucracies that flourished around the dark nucleus of the Central Committee than they were on the actual heart of the totali tarian machine, especially from the time when it reached perfection towards the end of the 1930s. On the whole it has remained as mysterious a creature as ever, an oyster which refuses to be prised open. We know very little about the Politburo in the 1940s and 1950s, either through the caprices of Russia’s policy on the declassification of archives, or, more probably, owing to the desire of the Soviet leaders themselves to hide from posterity the innermost springs of their conduct, or else because of the successive purges carried out in the archives by Stalin’s heirs, anxious to wipe away all traces of their crimes. This is the context in which we must judge the value of a testimony such as Sergo Beria’s. The story told by the son of the man whom people called Stalin’s butcher takes us, over many years, right inside the narrow circle within which everything in the USSR and a large part of the world was decided. As Stalin’s right-hand man for a long time, Beria holds the keys to many secrets of the Politburo. Like Eichmann and Mengele for the Nazis, he symbolises the worst of the Communist excesses within his own country and beyond. His name still evokes a vitriolic hatred in the hearts of many in the West and in Eastern Europe, and his popular image is that of a sinister, sadistic spymaster with whips in his office and the habit of driving down the windswept avenues of Moscow on the prowl for women. It is this combination of an insatiable libido matched by ruthless ambition, unspeakable cruelty and an explosive temper that set Beria truly apart from other Politburo. Having - some say - poisoned Stalin when he became infirm on 5 March 1953, Beria combined the internal and external security services under his command the next day, in a move that made him seem destined to take Stalin’s chair. Had his colleagues not struck him down a hundred days later by arresting, trying and executing him on charges of being among other things a British spy, it would have appeared viii Beria, My Father at the time that the man considered Stalin’s evil genius was well on his way to replacing his former master and surpassing him in cruelty. To be sure, Stalin had had no need of instigation from Beria in order to launch collectivisation, deport the kulaks (peasants), starve the Ukrainians to death, set up the trials and organise the ‘great terror’ of 1937. But Beria was no mean helper in implementing those horrors at a local level when he was still a Party chief in Georgia. He had organised and directed the terror in his own fiefdom, where the period 1937-1938 has left a frightful memory. Torture was practised on a large scale and there are several testimonies to torture sessions presided over by Beria in person in Tbilisi and, later, in Moscow. When Beria replaced the Russian Yezhov at the head of the NKVD at the end of 1938, he put an end to the ‘great terror’ (evidently at Stalin’s behest) and released a large number of pris oners, but without ceasing to practise repression and torture. He organised the massacre of the Polish officers at Katyn in the spring of 1940, the assassination of Trotsky, the deportation of the peoples and the repressive measures taken during the war. He remained at the head of the NKVD until January 1946, when perhaps even Stalin had started to fear the man he had created and ordered him to devote himself to building the atomic bomb and administering some vital sectors of the Soviet economy. The testimonies also confirm the kidnapping of women and what people in Tbilisi called Beria’s ‘Sultan’s habits’. But what constitutes the excitement of these memoirs is also why we should exercise care while reading them. Sergo Beria grew up in a world of lies and of half-truths, lies that were all the more inextricable because the truth was unbearable. Like all of his generation, he was exposed to surreal ideological beliefs. Added to this was the position of his father, whose activities were barely mentioned in the family but echoes of which must have reached his son’s ears. Above all there was the ambiguity of Lavrenti Beria himself: outwardly an efficient servant of the Soviet regime, but one whose dominant passion seems to have been a deep hatred of his fellow Georgian, Stalin. Plunged since his earliest years into a world of pretences, young Sergo himself took refuge in the certainties of the heart. Between his mother, who still idolised Stalin, and tried to protect Sergo from cruel reality and his father, who succeeded less and less in hiding from him his execration of the dictator, this model son was torn in two, and this ambivalence still marks the work that we have before us. The trial and execution of his father at the hands of Khrushchev, in 1953, months after Stalin’s death, and the subsequent blackening of his father’s name, was a body blow from which Sergo Beria never truly recovered. In this book he speaks as before an imaginary jury, poised to pass judgment. Throughout his life he has sought to act the witness for the defence - first by becoming an exemplary Soviet citizen who made Red Army missiles for the man who had caused his father’s downfall, then, after the perestroika, by publishing his own version, sometimes a very subjective one, of the facts, and particularly of those things of which his father was accused. It Editor’s Preface ix is one reason why an integral part of this book is the extensive apparatus of notes corroborating Sergo Beria’s testimony, or contradicting it, as the case may be. Sergo Beria’s testimony is also part of those endless, bickering feuds of Communists - or for that matter participants of any failed totalitarian regime - apportioning blame on one another by revealing choice sections of the truth. Both Stalin’s daughter Svetlana Allilueva and Khrushchev wrote their memoirs. Sergo’s is the third (and probably last) to appear from someone within Stalin’s circle. Beria is today perceived in accordance with history as written by Khrushchev. It was Khrushchev who, for obvious reasons, first styled the chief of Stalin’s police a cold-blooded monster, a primitive brute, a sadistic torturer, a diabolical intriguer, a sex maniac crouched on the lookout in his black limousine as he drove about Moscow, grabbing women off the streets. To the end of his life Khrushchev remained very proud of having liquidated Beria. After all, it was thanks to the coup d’etat that he organised against Beria that Khrushchev took power and managed to establish, to some degree, the legitimacy of his posi tion within the Party’s ruling elite. In order that his exploit might be properly appreciated, Beria’s image had to be painted as black as possible. This was one of the reasons for the trial of Beria and his accomplices being held in camera in 1953, ending in their death sentences in December of that year. Another reason for that trial was acknowledged later by Khrushchev - it was a first attempt at taking account of Stalin’s crimes without accusing Stalin himself, putting responsibility for them on to ‘the Beria gang’ and presenting Beria as ‘Stalin’s evil genius’. This version was taken up by Svetlana Allilueva, for understandable reasons. She had already been encouraged to take this line by Stalin himself. In its most brilliant passages this book shows that Stalin knew the art of making out his wicked actions to be initiatives forced on him by those around him, and he loved making Beria play the role of ‘the bad man’ (for example, when he presented him to Roosevelt as ‘our Himmler’, a joke which greatly embarrassed the American president). At Stalin’s court Khrushchev survived by playing the buffoon, Beria by playing the executioner. Each had the right physique for the job. It is on the mentality of the Soviet leaders that this book offers the most interesting revelations. The deep-seated hatred of Russia and the far- reaching importance of nationality in the power balance comes as a surprise (see more about this in the Editor’s Note). As we read, we find that they are all aware that they are participating in a criminal regime and committing infamous deeds. Some of them, at least, know that they will have accounts to render to posterity. Every apparatchik of a certain rank begins to compile dossiers that compromise his rivals and potential oppo nents. These dossiers concern crimes committed by order of higher authority. Like a Mafia ‘godfather’, Stalin takes care to compromise his confederates in systematic fashion, and any attempt to get out of this duty to murder, collectively or individually, brings down his suspicion and his X Beria, My Father vengeance. The Soviet regime emerges as a regime of blackmailers, a supremely hypocritical regime in which vice never stops paying homage to virtue and in which baseness disguises itself as duty, cowardice as altruism, treason as charity, sadism as efficiency, stupidity as patriotism. Yet the great historical interest of this book extends far beyond Kremlin gossip. This is most of all a document about daily life at the Kremlin. Khrushchev’s memoirs are full of gaps, self-justifications and even just plain lies, yet they constitute, in spite of that, a fascinating and irreplace able document for the historian. This book, too, adds to our knowledge, in particular to the role of anti-Russian sentiment and Beria’s surprising part in this. To be sure, Beria confided little to his son regarding his activ ities and plans. But the young man had the gift of observation, a delicate sensibility and the sharp memory characteristic of all who live in the midst of what is left unspoken. He frequented the company of his father’s helpers, high-ranking military men, some members of the Politburo and their wives. He looked on Stalin with the adoring eyes of a teenager, then observed him through his father’s implacable gaze. Time has stood still for him. Moreover, Sergo Beria significantly chose a career that was very different from his father, an unassuming job as an engineer. However much he may fail, his struggle to come to terms with a horrendous and painful past is a serious one, as serious as the system and the family he grew up in allowed. Franqoise Thom