Beria - My Father: Inside Stalin's Kremlin PDF

Preview Beria - My Father: Inside Stalin's Kremlin

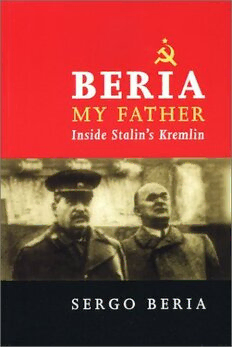

Beria, My Father Inside Stalin's Kremlin SERGO BERIA Edited by Fran~oise Thom English translation by Brian Pearce Duckworth First published in 2001 by Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd. 61 Frith Street, London WlD 3.JL Tel: 020 7434 4242 Fax: 020 7434 4420 Email: [email protected]. uk www.ducknet.co.uk © 1999 Sergo Beria © Editorial notes and comment 1999/2001 Franc;oise Thom © Translation 2001 Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd The moral right of Sergo Beria to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance With the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The right of Brian Pearce to be identified as the translator of this Work has been asserted in accordance with Sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 Originally published as BERIA mon pere © Pion/Criterion, Paris, France, 1999. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN O 7156 3062 8 Typeset by Derek Doyle and Associates, Liverpool Printed in Great Britain by Bookcraft (Bath) Ltd, Midsomer Norton, Avon Contents Editor's Preface Fran<;oise Thom vii Editor's Note Francoise Thom xi 1. In Stalin's Shadow 1 2. The NKVD 33 3. Hitler 47 4. War 69 5. 'Peace' 103 6. Stalin 133 7. The People around Stalin: 150 8. The Bomb 172 9. Disillusionment 195 10. Stalin's Grand Design 223 11. The first de-Stalinisation 251 12. Fall 268 13. Who Was My Father? 279 Author's Epilogue Sergo Beria 297 Appendix 299 Notes 302 Bibliography and Sources Used for the Notes 374 Biographical Notes 379 Index of Names 386 Index of Places 394 Editor's Preface After the collapse of Communism and the partial opening of the Soviet archives, historians of the USSR and of Communism enjoyed a period of euphoria. At last we were going to learn what had gone on in the entrails of the sphinx, the jealously-guarded secrets of the Kremlin were to be exposed to the gaze of outsiders ... These expectations were fulfilled only in part. The Soviet archives made available were, in fact, far more eloquent concerning the peripheral mechanisms of the regime and on the working of the bureaucracies that flourished around the dark nucleus of the Central Committee than they were on the actual heart of the totali tarian machine, especially from the time when it reached perfection towards the end of the 1930s. On the whole it has remained as mysterious a creature as ever, an oyster which refuses to be prised open. We know very little about the Politburo in the 1940s and 1950s, either through the caprices of Russia's policy on the declassification of archives, or, more probably, owing to the desire of the Soviet leaders themselves to hide from posterity the innermost springs of their conduct, or else because of the successive purges carried out in the archives by Stalin's heirs, anxious to wipe away all traces of their crimes. This is the context in which we must judge the value of a testimony such as Sergo Beria's. The story told by the son of the man whom people called Stalin's butcher takes us, over many years, right inside the narrow circle within which everything in the USSR and a large part of the world was decided. As Stalin's right-hand man for a long time, Beria holds the keys to many secrets of the Politburo. Like Eichmann and Mengele for the Nazis, he symbolises the worst of the Communist excesses within his own country and beyond. His name still evokes a vitriolic hatred in the hearts of many in the West and in Eastern Europe, and his popular image is that of a sinister, sadistic spymaster with whips in his office and the habit of driving down the windswept avenues of Moscow on the prowl for women. It is this combination of an insatiable libido matched by ruthless ambition, unspeakable cruelty and an explosive temper that set Beria truly apart from other Politburo. Having - some say - poisoned Stalin when he became infirm on 5 March 1953, Beria combined the internal and external security services under his command the next day, in a move that made him seem destined to take Stalin's chair. Had his colleagues not struck him down a hundred days later by arresting, trying and executing him on charges of being among other things a British spy, it would have appeared viii Beria, My Father at the time that the man considered Stalin's evil genius was well on his way to replacing his former master and surpassing him in cruelty. To be sure, Stalin had had no need of instigation from Beria in order to launch collectivisation, deport the kulaks (peasants), starve the Ukrainians to death, set up the trials and organise the 'great terror' of 1937. But Beria was no mean helper in implementing those horrors at a local level when he was still a Party chief in Georgia. He had organised and directed the terror in his own fiefdom, where the period 1937-1938 has left a frightful memory. Torture was practised on a large scale and there are several testimonies to torture sessions presided over by Beria in person in Tbilisi and, later, in Moscow. When Beria replaced the Russian Yezhov at the head of the NKVD at the end of 1938, he put an end to the 'great terror' (evidently at Stalin's behest) and released a large number of pris oners, but without ceasing to practise repression and torture. He organised the massacre of the Polish officers at Katyn in the spring of 1940, the assassination of Trotsky, the deportation of the peoples and the repressive measures taken during the war. He remained at the head of the NKVD until January 1946, when perhaps even Stalin had started to fear the man he had created and ordered him to devote himself to building the atomic bomb and administering some vital sectors of the Soviet economy. The testimonies also confirm the kidnapping of women and what people in Tbilisi called Beria's 'Sultan's habits'. But what constitutes the excitement of these memoirs is also why we should exercise care while reading them. Sergo Beria grew up in a world of lies and of half-truths, lies that were all the more inextricable because the truth was unbearable. Like all of his generation, he was exposed to surreal ideological beliefs. Added to this was the position of his father, whose activities were barely mentioned in the family but echoes of which must have reached his son's ears. Above all there was the ambiguity of Lavrenti Beria himself: outwardly an efficient servant of the Soviet regime, but one whose dominant passion seems to have been a deep hatred of his fellow Georgian, Stalin. Plunged since his earliest years into a world of pretences, young Sergo himself took refuge in the certainties of the heart. Between his mother, who still idolised Stalin, and tried to protect Sergo from cruel reality and his father, who succeeded less and less in hiding from him his execration of the dictator, this model son was torn in two, and this ambivalence still marks the work that we have before us. The trial and execution of his father at the hands of Khrushchev, in 1953, months after Stalin's death, and the subsequent blackening of his father's name, was a body blow from which Sergo Beria never truly recovered. In this book he speaks as before an imaginary jury, poised to pass judgment. Throughout his life he has sought to act the witness for the defence - first by becoming an exemplary Soviet citizen who made Red Army missiles for the man who had caused his father's downfall, then, after the perestroika, by publishing his own version, sometimes a very subjective one, of the facts, and particularly of those things of which his father was accused. It Editor's Preface ix is one reason why an integral part of this book is the extensive apparatus of notes corroborating Sergo Beria's testimony, or contradicting it, as the case may be. Sergo Beria's testimony is also part of those endless, bickering feuds of Communists - or for that matter participants of any failed totalitarian regime - apportioning blame on one another by revealing choice sections of the truth. Both Stalin's daughter Svetlana Allilueva and Khrushchev wrote their memoirs. Sergo's is the third (and probably last) to appear from someone within Stalin's circle. Beria is today perceived in accordance with history as written by Khrushchev. It was Khrushchev who, for obvious reasons, first styled the chief of Stalin's police a cold-blooded monster, a primitive brute, a sadistic torturer, a diabolical intriguer, a sex maniac crouched on the lookout in his black limousine as he drove about Moscow, grabbing women off the streets. To the end of his life Khrushchev remained very proud of having liquidated Beria. After all, it was thanks to the coup d'etat that he organised against Beria that Khrushchev took power and managed to establish, to some degree, the legitimacy of his posi tion within the Party's ruling elite. In order that his exploit might be properly appreciated, Beria's image had to be painted as black as possible. This was one of the reasons for the trial of Beria and his accomplices being held in camera in 1953, ending in their death sentences in December of that year. Another reason for that trial was acknowledged later by Khrushchev - it was a first attempt at taking account of Stalin's crimes without accusing Stalin himself, putting responsibility for them on to 'the Beria gang' and presenting Beria as 'Stalin's evil genius'. This version was taken up by Svetlana Allilueva, for understandable reasons. She had already been encouraged to take this line by Stalin himself. In its most brilliant passages this book shows that Stalin knew the art of making out his wicked actions to be initiatives forced on him by those around him, and he loved making Beria play the role of 'the bad man' (for example, when he presented him to Roosevelt as 'our Himmler', a joke which greatly embarrassed the American president). At Stalin's court Khrushchev survived by playing the buffoon, Beria by playing the executioner. Each had the right physique for the job. It is on the mentality of the Soviet leaders that this book offers the most interesting revelations. The deep-seated hatred of Russia and the far reaching importance of nationality in the power balance comes as a surprise (see more about this in the Editor's Note). As we read, we find that they are all aware that they are participating in a criminal regime and committing infamous deeds. Some of them, at least, know that they will have accounts to render to posterity. Every apparatchik of a certain rank begins to compile dossiers that compromise his rivals and potential oppo nents. These dossiers concern crimes committed by order of higher authority. Like a Mafia 'godfather', Stalin takes care to compromise his confederates in systematic fashion, and any attempt to get out of this duty to murder, collectively or individually, brings down his suspicion and his X Beria, My Father vengeance. The Soviet regime emerges as a regime of blackmailers, a supremely hypocritical regime in which vice never stops paying homage to virtue and in which baseness disguises itself as duty, cowardice as altruism, treason as charity, sadism as efficiency, stupidity as patriotism. Yet the great historical interest of this book extends far beyond Kremlin gossip. This is most of all a document about daily life at the Kremlin. Khrushchev's memoirs are full of gaps, self-justifications and even just plain lies, yet they constitute, in spite of that, a fascinating and irreplace able document for the historian. This book, too, adds to our knowledge, in particular to the role of anti-Russian sentiment and Beria's surprising part in this. To be sure, Beria confided little to his son regarding his activ ities and plans. But the young man had the gift of observation, a delicate sensibility and the sharp memory characteristic of all who live in the midst of what is left unspoken. He frequented the company of his father's helpers, high-ranking military men, some members of the Politburo and their wives. He looked on Stalin with the adoring eyes of a teenager, then observed him through his father's implacable gaze. Time has stood still for him. Moreover, Sergo Beria significantly chose a career that was very different from his father, an unassuming job as an engineer. However much he may fail, his struggle to come to terms with a horrendous and painful past is a serious one, as serious as the system and the family he grew up in allowed. Franc;oise Thom Editor's Note Sergo Beria's book can be approached in two distinct ways. The first consists of 'neutral' parts, those in which his father was not directly involved and where the author's will to construct an apologia does not entail the risk of Sergo distorting the truth. Even with this restricted approach the reader will find a wealth of material about the Stalin period and the causes of the Terror. His opening chapters reveal everything from the mentality of the leaders of the republics of the USSR, their relations with Moscow, the extent and limits of their power within their respective fiefs, to their ways of life, the way in which local intrigues were interwoven with the struggle for power at the top, Moscow's instruments of control and the role played by the republics in the aims of the foreign policy a worked out in Moscow. After Beria's arrival in the capital we find vivid picture of Stalin's immediate entourage, of groups tearing each other apart and of the byzantine forms assumed by this perpetual fight to the death, including an analysis of Stalin's policy on the eve of the war. But Sergo Beria's story is also a unique testimony of the war as experi enced by a son of the nomenklatura and of how he saw relations with the Western allies. There are colourful portraits of the members of the Politburo and their wives after the war, a breathtaking description of Stalin's strategy for controlling his world and calling the country to heel after the relatively 'liberal' period of the war, and his insistence on the priority to be given to the nuclear project in a USSR in ruins. Sergo Beria vividly captures the exacerbation of the struggle for the succession at the time when Stalin's physical decline became obvious. Finally, we can follow him in his evocative description of the madness of Stalin's last months, which is fully corroborated by the accounts left by other witnesses and by what the archives have revealed. Moreover, Sergo's narrative must be read throughout against the salient fact that Stalin and Beria were two Georgians ruling the vast Russian empire and its dominions, and that Stalin's death must have upset the delicate balance that existed. The second approach concerns itself directly with the question of what we are to believe in the testimony of a son about a father whom he clearly worshipped. Should we reject everything because of the evident partiality of the writer and of what we know of Beria from other sources? To what extent do these descriptions of Beria by Stalin and Khrushchev correspond to reality? What this enquiry amounts to is granting Sergo Beria his wish of xii Beria, My Father allowing history to pass judgement on his father. There is obviously no question here of rehabilitating Beria - even his son is not attempting that - but of putting together all the evidence in his case. Beria committed many crimes, but the same can be said of his colleagues in the Politburo who sent thousands to their deaths. Khrushchev, for example, distin guished himself by his zeal in the purges carried out in Moscow and then in the Ukraine, and certainly had no less blood on his conscience than Beria. But he beat Beria in the fight for the succession to Stalin and there fore was able to put his hands on the archives, destroying documents that incriminated him, concocting for posterity his own version of the past, and showing more concern to put himself in a good light and 'compromise' his rivals than to serve the cause of truth. But the indisputable truth is that they both took an active part in a deeply criminal regime. Khrushchev's version remained almost intact until the declassification in 1991 of the minutes of the July 1953 Plenum, which was devoted to condemning Beria after his arrest on 26 June 1953 and until statements were made by some pioneers of perestroika such as the Russian A. Yakovlev, who did not hesitate to name Beria as the only real reformer among Stalin's successors. It was the minutes of the July 1953 Plenum which led the author of these lines to take an interest in Beria as an indi vidual and to record the testimony offered by his son. Research in newly declassified archives has led to remarkable discov eries. They have raised rather than answered questions about this character who was the most powerful man in the USSR for such a short period of time. As said before, Beria did not resume direction of the police and state security services (now also including the precursor of the KGB) until 6 March 1953, the day after Stalin's death. Yet, instead of consolidating his mammoth power and deploying his newly regained control over the secu rity files on his colleagues, Beria started bombarding them with an array of initiatives to de-Stalinise the USSR. To be sure, there was a widely shared consensus about the need for de Stalinisation. But this did not extend to all the matters Beria put forward in rapid succession. From 6 March he reduced the economic jurisdiction of the police and announced that he wanted to pass responsibility for the Gulag on to the Ministry of Justice. On 13 March he charged four NKVD committees with re-examining some notorious show trials, including the trial of the Jewish Antifascist Committee, and persecution of the Jews ended forthwith. On 14 March, the State and Party apparatus were sepa rated, with Malenkov becoming President and Khrushchev Leader of a weakened Communist Party. On 15 March, Beria gained control over censorship, the Glavlit, and expunged Stalin's name from the press in a very short time, while anti-Western propaganda became muted. On 21 March, Beria attacked the Stalinised central state and proposed ending the giant Socialist construction sites (which would in turn end the need for the Gulag). Three days later he addressed a paper to the Presidium in Editor's Note xiii which he detailed that there were 2,526,402 people in the Gulag, of whom 221,435 were 'State criminals'. On 27 March, 1,178,422 prisoners were freed and their numbers continued to swell under his stewardship until his fall from power (from July the Gulag complement went up again). In a secret memorandum circulated to the NKVD on 4 April, Beria forbade torture in prisons and detention centres. On the same day, Pravda carried an NKVD announcement which cleared Jewish doctors (accused by Stalin in the previous year of wanting to poison Politburo members). It was the first public attack against Stalin, it left the country reeling, and Beria had imposed it on his reluctant colleagues. In order to soften their resistance he had them listen to tapes of Stalin, in which he demanded the torture of people accused of certain things and revealed the extent of his paranoia. Famous writers like K. Simonov attended these sessions. Curiously, many of the charges brought against Beria at his show trial departed from the usual allegations formulated in this sort of Communist ceremony. True, Beria was described as a British agent and was said to have wished to organise a coup d'etat and to have put the security organs above control by the Party. Alongside these ritual litanies (which included the accusation that he had tried to undermine collective cattle breeding and vegetable production programmes), however, there were other precise accusations of an unfamiliar kind, the addition of which outlined a polit ical project that was coherent and far-reaching. They implied overturning Soviet foreign policy (Beria wanted to hand over the GDR to the German Federal Republic), setting aside the Communist Party (Beria wanted to deprive it of control over the economy), a reform of the empire (Beria wanted to release the republics from Russian domination) and introducing glasnost (Beria wanted to end the jamming of Western broadcasts). The speakers at the Plenum took turns in declaring that 'Beria was no Communist'. Strange as it may seem, a charge of that sort was not routine in such circumstances. One would have expected to find that he was accused of 'right deviationism' or 'Trotskyism'. It is enough to compare the July 1953 Plenum with those of February 1955 and June 1957, when Malenkov and the 'anti-Party group' were condemned, in order to appre ciate the degree to which the Soviet leaders felt threatened by Beria. Nothing came near the hatred that broke over their fallen Georgian colleague. And this hatred is certainly not explained just by Beria's past crimes. (In his memoirs Khrushchev writes a eulogy on the Russian Yezhov, Beria's predecessor at the NKVD and the organiser of the 'great terror'.) Looking at the archives, Beria launched his national policy in April. He started by sending NKVD officers to the republics of the USSR, charging them to find out what was happening there and, most of all, to find compromising facts on Party dignitaries. Based on these reports of the flagrant collapse of Party policies, Beria addressed a number of recom mendations to his colleagues. They all pointed in the same direction: ending the Russian tutelage of the republics. Beria, for example, proposed to recall the Russian Party functionaries from the Baltic States, to cease