Barnato AE, Berhane Z, Weissfeld LA, Chang CCH, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, on behalf of PDF

Preview Barnato AE, Berhane Z, Weissfeld LA, Chang CCH, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, on behalf of

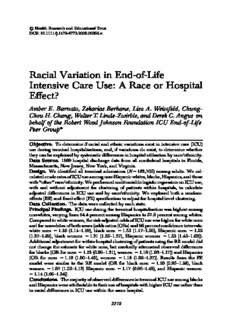

rHealthResearchandEducationalTrust DOI:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00598.x Racial Variation in End-of-Life Intensive Care Use: A Race or Hospital Effect? Amber E. Barnato, Zekarias Berhane, Lisa A. Weissfeld, Chung- ChouH.Chang,WalterT.Linde-Zwirble,andDerekC.Angus on behalf of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ICU End-of-Life Peer Groupn Objective. Todetermineifracialandethnicvariationsexistinintensivecare(ICU) useduringterminalhospitalizations,and,ifvariationsdoexist,todeterminewhether theycanbeexplainedbysystematicdifferencesinhospitalutilizationbyrace/ethnicity. Data Source. 1999hospitaldischargedata from allnonfederalhospitalsinFlorida, Massachusetts,NewJersey,NewYork,andVirginia. Design. We identified all terminal admissions(N5192,705) among adults. We cal- culatedcruderatesofICUuseamongnon-Hispanicwhites,blacks,Hispanics,andthose with‘‘other’’race/ethnicity.WeperformedmultivariablelogisticregressiononICUuse, with and without adjustment for clustering of patients within hospitals, to calculate adjusted differencesinICUuseand byrace/ethnicity.Weexploredbotharandom- effects(RE)andfixed-effect(FE)specificationtoadjustforhospital-levelclustering. DataCollection. Thedatawerecollectedbyeachstate. PrincipalFindings. ICUuseduringtheterminalhospitalizationwashighestamong nonwhites,varyingfrom64.4percentamongHispanicsto57.5percentamongwhites. Comparedtowhitewomen,therisk-adjustedoddsofICUusewashigherforwhitemen andfornonwhitesofbothsexes(oddsratios[ORs]and95percentconfidenceintervals: white men 51.16 (1.14–1.19), black men 51.35 (1.17–1.56), Hispanic men 51.52 (1.27–1.82), black women 51.31 (1.25–1.37), Hispanic women 51.53 (1.43–1.63)). Additionaladjustmentforwithin-hospitalclusteringofpatientsusingtheREmodeldid notchangetheestimateforwhitemen,butmarkedlyattenuatedobserveddifferences forblacks(ORformen 51.12(0.96–1.31),women 51.10(1.03–1.17))andHispanics (OR for men 51.19 (1.00–1.42), women 51.18 (1.09–1.27)). Results from the FE model were similar to the RE model (OR for black men 51.10 (0.95–1.28), black women 51.07 (1.02–1.13) Hispanic men 51.17 (0.96–1.42), and Hispanic women 51.14(1.06–1.24)) Conclusions. ThemajorityofobserveddifferencesinterminalICUuseamongblacks andHispanicswereattributabletotheiruseofhospitalswithhigherICUuseratherthan toracialdifferencesinICUusewithinthesamehospital. 2219 2220 HSR:HealthServicesResearch41:6(December2006) Key Words. Intensive care units, terminal care, life support care, ethnic groups, hospitals One in five Americans die in the hospital using intensive care unit (ICU) services, and these hospitalizations consume over 80 percent of all terminal hospitalizationcosts(Angusetal.2004).Variationsinend-of-lifeICUadmis- sionexistbygeography(WennbergandCooper1999)andage(Yuetal.2000; Levinskyetal.2001;Angusetal.2004),butlessisknownaboutracialorethnic differencesinICUuseattheendoflife(Degenholtzetal.2003).Paradoxically, racialvariationsinend-of-lifecareappeartofollowanentirelydifferentpat- tern than is observed for other medical services in the United States. While minorities,andblacksinparticular,generallyaretreatedlessintensivelythan whites (Smedley et al. 2002), including lower rates of invasive cardiac pro- cedures(Ayanianetal.1993;Whittleetal.1993),surgicaltreatmentforlung cancer(Bachetal.1999),andrenaltransplantation(Epsteinetal.2000),blacks appear to receive higher rates of intensive treatment at the end of life. For example,blacks are more likely to die in the hospital (Pritchard et al. 1998) and less likely to use hospice (Greiner et al. 2003) and have higher overall spendingintheirlast12monthsthanwhites(Hoganetal.2001;Levinskyetal. 2001; Shugarman et al.2004). As dying patients can be considered more or lessequivalentintheirillnessseverity(Fisheretal.2003a,b),studiesofend-of- life treatment variations are less subject to confounding by inadequate risk- adjustment methodology. Many scholars have tried to explain these phe- nomena by citing differences in patient preferences. Indeed, several studies AddresscorrespondencetoAmberE.Barnato,M.D.,M.P.H.,M.S.,AssistantProfessor,Depart- mentofMedicine,SchoolofMedicine,DepartmentofHealthPolicyandManagement,Graduate School of Public Health, Center for Research on Health Care, University of Pittsburgh, 200 MeyranStreet,Suite200,Pittsburgh,PA15213.ZekariasBerhane,Ph.D.,AssistantProfessor,is with theDepartmentofEpidemiologyandBiostatistics,SchoolofPublicHealth,DrexelUni- versity,PA.LisaA.Weissfeld,Ph.D.,Professor,iswiththeDepartmentofBiostatistics,Graduate SchoolofPublicHealth,UniversityofPittsburgh,PA.Chung-ChouH.Chang,Ph.D.,Assistant Professor,iswiththeDepartmentofMedicine,SchoolofMedicine,DepartmentofBiostatistics, GraduateSchoolofPublicHealth,CenterforResearchonHealthCare,UniversityofPittsburgh, PA.WalterT.Linde-ZwirbleisVicePresidentandChiefScienceOfficer,ZDAssociates,PA. DerekC.Angus,M.D.,M.P.H., Professor andVice Chair,isDirector,CRISMALaboratory, DepartmentofCriticalCareMedicine,SchoolofMedicine,DepartmentofHealthPolicyand Management,GraduateSchoolofPublicHealth,UniversityofPittsburgh,PA. nMembersarelistedintheAppendix RaceandEnd-of-LifeICUUse 2221 report thatblacksand Hispanicsprefer moreaggressivelife-sustainingtreat- ment than whites (Garrett et al. 1993; O’Brien et al. 1995; McKinley et al. 1996; Diringer et al. 2001), and that physicians’ preferences for end-of-life treatmentfollowthesamepatternbyraceaspatients’preferences(Mebaneet al. 1999). However, we also know that treatment preferences for care at the endoflifedonotreliablypredictactualtreatment(Tenoetal.1997;Pritchard etal.1998),andsoitseemsimplausiblethatpreferencesalonedriveobserved patternsofcare. Becauseminoritypopulationsoftenliveindifferentneighborhoodsand accessdifferentprovidersthanmajoritypopulations,observeddifferencesin treatmentpatternsmaybeafunctionofphysicianorhospitalandnotraceper se(Kahnetal.1994;Skinneretal.2003;Bachetal.2004;Bradleyetal.2004; Barnatoetal.2005).Indeed,atthehospitalreferralregion,racialdifferencesin end-of-lifeMedicarespendingaredrivenmorebyregionofresidencethanby race (Baicker et al. 2004). If dying patients seek care at the nearest hospital ratherthanatthehospitalthatprovidesthetypeofcarepatternstheyprefer, andminoritypopulationsusesystematicallydifferenthospitalsthanmajority populationsduetoresidentialsegregationintheUnitedStates,thenprevailing hospitalpracticepatternsmaydriveend-of-lifetreatmentintensityratherthan patient preferences. Clarifying this issue is critical to inform any policy de- signedtobettermatchpatients’preferenceswithtreatment. In this study we explore the relationship between race/ethnicity and ICUadmissionandcostsamongpatientswhodiedinthehospital.Weasked two questions. Do differences exist? And, if so, can they be explained by providerratherthanbyraceandethnicity? METHODS AnalyticSample Weretrospectivelyidentifiedallnonfederalhospitaldischargesin1999from five states, Florida (FL), Massachusetts (MA), New Jersey (NJ), New York (NY),andVirginia(VA),usingstatehospitaldischargedata.Wethenselected all adults (age (cid:1)18) whose discharge status was ‘‘dead’’ to identify patients whodiedinanacutecarehospital.Fromeachdecedent’sterminaladmission, we abstracted the patient’s age, sex, race (white non-Hispanic, black non- Hispanic, Hispanic, and other), International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision,ClinicalModification(ICD-9-CM)diagnosesandprocedures,dates and type of admission (urgent/emergent medical, elective surgical, urgent/ 2222 HSR:HealthServicesResearch41:6(December2006) emergent surgical), hospital provider number, insurance status (expected sourceofpaymentlistedasMedicaid,Medicare,commercial,otherinsured, uninsured), and use of intensive care. We used ICD-9 diagnosis codes to identifythepresenceofeachof15Charlson–Deyocomorbidies(Deyoetal. 1992)inprimaryandsecondarydiagnosisfields.Thesecomorbiditiesinclud- ed myocardial infarction, diabetes, diabetes with complications, peripheral vasculardisease(PVD),cerebrovasculardisease,hemiplegia,chronicpulmo- narydisease,mildliverdisease,severeliverdisease,renaldisease,rheumato- logicdisease,malignancy,metastaticsolidtumor,HIVinfection,anddemen- tia. We entered each diagnosis into the regression models as a categorical indicatorvariableratherthanasaweightedCharlsonscorebecausethescore weightingwasdeveloped toriskadjustformortality(notICUuse).Asallof ourpatientsdiedtheCharlsonscorewouldnotnecessarilybetheappropriate weightingforriskadjustment;rather,wewantedtoadjustfordifferentialeffect ofindividualdiagnosesonICUadmission.Forexample,somediagnoses,such ascancers,makeICUadmissionlesslikely(Angusetal.2004).Wecategorized patientswhoseonlysurgicalprocedurewasatracheostomy(40percentofall patients with tracheostomy) as medical admissions rather than surgical ad- missionsundertheassumptionthattheseweremedicaladmissionswithpro- longedmechanicalventilation.Weexcludedpatientswithmissingrace(N5 11,938).Weadditionallyremovedonehospitaloutlierinwhichnodecedents (N51,784)receivedintensivecareservices,suggestingcodingerror. DependentVariables ICUServices. WecategorizedanydecedentwithICUorCoronaryCareUnit (CCU)roomcharges40orwhowasmechanicallyventilatedasusing‘‘ICU services’’ during the admission. We used mechanical ventilation in the absence of ICU charges to capture services delivered in intermediate care units.DatesofICUadmissionorofextubationarenotavailableinthesedata. ICUlengthofstay(LOS),availableforthreeofthefivestates(MA,NJ,and NY),wasthesameashospitalLOSin40percentofterminaladmissionswith ICU care. Of the remaining admissions, we could not determine if persons whodiedinthehospitalfollowingICUadmissionwerestillintheICUonthe dayofdeath(e.g.,died‘‘in’’anICU)orhadbeentransferredtoageneralfloor or step-down unit, although in the majority of cases the hospital LOS was (cid:2) 1 day longer than the ICU LOS. To address this uncertainty, we define thedependentvariableforthisanalysisasdeath‘‘withICUservices’’rather thandeath‘‘inanICU’’perse. RaceandEnd-of-LifeICUUse 2223 HospitalAdmissionPatterns WecalculatedtherateofterminalICUadmissionamongwhitedecedentsat eachhospital.Wethenarrayedhospitalsintodecilesoflowesttohighestwhite intensivecareuse.Usinghospitalswithatleastfiveblackdecedents(n5408 hospitals),wethendeterminedtheproportionofallblackandwhiteinpatient decedents who were treated at hospitals within each decile. Finally, we cal- culated the black and white terminal admission rates within each decile of whiteterminalICUuseforcomparison. StatisticalAnalysis We categorized patients into those whose terminal admission included ICU servicesandthosewhosedidnotandcalculatedterminalhospitalizationcosts foreachpatient. Weexploredtheunivariaterelationshipsbetweenage,sex, race, clinical condition, admission type, and insurance status and ICU ad- mission. Age was not linearly related to ICU use, so we specified age as a categorical variable (18–24, 25–34, 35–54, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85– 89, 90–94, (cid:1) 95 years) for regression analyses. For each race/ethnic group, wecompareddemographicandclinicalcharacteristicsusingaw2testfordif- ference. We explored whether observed racial and ethnic differences in the useofICUservicesattheendoflifepersistedafteradjustmentfordifferences inthesecharacteristicsusingmultivariablelogisticregressionmodels.Were- tained independent variables and any interactions with race/ethnicity using backward stepwise selection with coefficients significant at the po.05 level. Wethenusedtwodifferentstatisticalmethodstoadjustfortheeffect,beyond case-mix bias, of provider-level clustering: generalized estimating equations (GEE), which treats hospital as a random effect (RE), and fixed effects (FE) logisticregression.IncontrasttotheGEE(ZegerandLiang1986;Localioetal. 2001;Greenfieldetal.2002;Panageasetal.2003)approachmostcommonly usedinthehealthservicesresearchliterature(whichtreatseachhospitalasa setofrepeatedmeasuresandadjustsforunobservedhospital-levelfactorsthat were omitted from the model and which systematically raise or lower utili- zation of all patients in that hospital) the FE logistic regression estimates a separate intercept for each hospital. The FE model does not make the as- sumptionthattheseunobservedhospitalcharacteristicsareuncorrelatedwith race. If, as we assert, black patients are more likely to die in hospitals with greater end-of-life intensive care use, models with hospital-level adjustment shouldproducestatisticallydifferentparametercoefficientestimatesthanthe modelwithoutthehospital-leveladjustment. 2224 HSR:HealthServicesResearch41:6(December2006) We report odds ratios (ORs) for ICU use, by race, compared to the groupwiththelowestuserate,whitewomen.Becausetheoutcomemodeledis common, the OR does not approximate the risk ratio and should be inter- pretedastheratioofthelogoddsofICUuse.WeusedSAS(version8.2,SAS Institute,Cary,NC)andSTATA(version8.2,StataCorp,CollegeStation,TX) to execute statistical analyses. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board and the authors had complete auton- omyfromthefundingagencyindataanalysesandmanuscriptpreparation. RESULTS SampleCharacteristics The analytic sample contained 192,705 patients who died in 674 acute care hospitals.Themean((cid:3)SD)ageofthepatientswas73.8(cid:3)14.9years(range, 18–113).Womencomprised51.1percentofthesample.Non-Hispanicwhites represented 70.8 percent of the patients, blacks 11.2 percent, Hispanics 5.7 percent, and ‘‘other’’ races 12.4 percent. Eighty-two percent of admissions wereurgent/emergentmedicaladmissions.TheprimarypayerwasMedicare for66.1percentofpatients,Medicaidfor4.5percent,andcommercialinsur- ancefor17.2percent,while3.3percentofdecedentswereuninsured.Eachof thedemographicandclinicalvariablesmeasuredweresignificantlydifferent between race/ethnicity subgroups (Table 1). Minorities were younger, had higherratesofdiabetes,liverdisease,renaldisease,andHIV;lowerratesof chronicpulmonarydiseaseandmyocardialinfarction;andweremorelikelyto beinsuredbyMedicaidortobeuninsured. HospitalAdmissionPatterns Black patients disproportionately died in hospitals with greater end-of-life ICUuseasmeasuredbythewhiteterminalICUadmissionrate(Figure1A). Yet within deciles of hospital terminal ICUadmission rates, the rate among blacksandnon-Hispanicwhiteswasroughlyequivalent(Figure1B). UseofICUServices Overall, 58.8 percent of terminal admissions involved ICU care. Sixty-four percent of black decedents, 64.4 percent of Hispanics, and 58.4 percent of othernonwhitesusedICUservicesduringtheterminaladmission,compared with 57.5 percent of non-Hispanic whites (Table 1). Adjusting for case mix usingdemographics,insurancestatus,admissiontype,andpresenceofchron- RaceandEnd-of-LifeICUUse 2225 Table1: DemographicandClinicalCharacteristicsofPatients White Black Hispanic Other Characteristic (N5136,338) (N521,591) (N510,883) (N523,893) p-Value Age(years) 75.6 65.5 70.7 72.1 o.0001 Women(%) 51.0 52.8 49.2 51.0 o.0023 Chronicconditions(%) Myocardialinfarction 3.0 1.2 1.8 2.1 o.0001 Diabetes 14.6 18.3 19.0 15.8 o.0001 Diabeteswithcomplications 2.6 4.7 3.0 2.8 o.0001 Peripheralvasculardisease 4.0 4.1 3.3 3.6 o.0001 Cerebrovasculardisease 2.8 3.8 2.7 3.2 o.0001 Hemiplegia 2.0 1.9 1.6 2.1 .0300 Chronicpulmonarydisease 17.2 9.2 12.7 12.9 o.0001 Mildliverdisease 3.2 3.8 6.6 4.2 o.0001 Severeliverdisease 2.7 3.6 5.4 3.7 o.0001 Renaldisease 5.2 6.8 6.1 5.7 o.0001 Rheumatologicdisease 1.5 1.4 1.0 1.5 .0022 Malignancy 19.8 20.1 18.5 21.1 o.0001 Metastaticsolidtumor 14.2 15.2 12.6 14.8 o.0001 HIVinfection 0.6 8.9 5.7 2.8 o.0001 Dementia 2.6 2.1 2.0 2.6 o.0001 Admissiontype(%)n Urgent/emergentmedical 81.1 80.8 81.7 80.1 o.0001 Urgent/emergentsurgical 15.5 16.9 15.7 16.7 Electivesurgical 3.4 2.3 2.6 3.3 Insurancetype(%)n Medicare 71.5 46.8 51.5 59.8 o.0001 Commercial 16.8 17.2 19.4 18.7 Medicaid 2.2 13.4 10.8 6.2 Otherinsured 7.2 15.7 12.6 10.2 Uninsured 2.2 7.0 5.8 5.1 Usedintensivecare(%) 57.5 64.1 64.4 58.4 o.0001 Medianhospitalization 7,511 9,653 9,557 9,257 o.0001 cost($) nMaynotsumto100%duetorounding. icconditions,blacksandHispanicswerestillmorelikelythannon-Hispanic white decedents to receive ICU care at the end of life (Figure 2). However, adjustmentfortheclusteringofpatientswithinhospitalsmarkedlyattenuated the differences for blacks and Hispanics, regardless of model specification (Figure 2). The magnitude of decrease between the case-mix adjustment modelandthemodelsthatadditionallyadjustforwithin-hospitalclusteringof black and Hispanic patients in Figure 2 reflects the degree to which these patients’careisdrivenbytheiruseofhospitalswithdifferentpracticepatterns (inthiscase,higherratesofend-of-lifeICUserviceuse). 2226 HSR:HealthServicesResearch41:6(December2006) Figure1: (A,B)IntensiveCareUnit(ICU)UseamongTerminalAdmissions, byDecileofHospitalTreatmentIntensity A B each decile 1250 Whites Blacks nsive care 10800%% Whites Blacks plein 10 g inte 60% am sin 40% s u nt of 5 ents 20% e d c e Per 0 Dec 0% Low High Low High Terminal ICU use Terminal ICU use We grouped 408hospitals into deciles arrayed from the group of hospitals with the lowest(21percent)tothehighest(87percent)terminalICUuseamongwhites(266of the674hospitalsarenotinthisfigurebecausetheytreatedo5blackdecedentsandwe couldnotcalculatea‘‘black’’rate).PanelAdemonstratesthatmoreblacksweretreated athigh(white)ICUusehospitals,whereasmorewhitesaretreatedatlowerICUuse hospitals.PanelBdemonstratesthatICUserviceamongblackandwhitedecedentsin each decile was roughly equivalent. Error bars represent 95 percent confidence in- tervalsaroundthedecilerateestimates. For12ofthechronicconditions,therewerenosignificantinteractions between race and disease. But for three conditions, PVD, metastatic solid tumors,andothermalignancies,theeffectoftheconditiononend-of-lifeICU servicefollowedadifferentpatternbyrace.Specifically,themodeladjusting forcasemixidentifiednosignificantdifferencesinICUuse,byrace,among decedents withPVD,increased useamong black menandwomen and His- panic women but not Hispanic men among decedents with metastatic solid tumors,andincreaseduseamongblackwomen,Hispanicmenandwomen, butnotblackmeninpatientswithothermalignancies.Inmodelsadjustingfor hospital-level clustering, black race remained significantly associated with higherICUuseduringtheterminaladmissionamongpatientswithmetastatic cancer. Theelderly,women,andthosewithnon-Medicareinsurancewereless likelytouseICUservices.Unlikerace,theparameterestimatesfortheeffectof age, gender, chronic conditions, and admission type were not significantly affectedbytheadditionaladjustmentforhospital-levelclustering,suggesting that these variables do not systematically vary between hospitals. In other RaceandEnd-of-LifeICUUse 2227 Figure2: The Odds of ICU Use during the Terminal Admission, by Race/Ethnicity 1.0 (−) White women 1.0 (−) 1.0 (−) 1.16 (1.14−1.19) White men 1.14 (1.12−1.17) 1.15 (1.12−1.18) 1.31 (1.25−1.37) Black women 1.10 (1.03−1.17) 1.07 (1.02−1.13) 1.35 (1.17−1.56) Black men 1.12 (0.96−1.31) 1.10 (0.95−1.28) 1.53 (1.43−1.63) Hispanic women 1.18 (1.09−1.27) 1.14 (1.06−1.24) 1.52 (1.27−1.82) Hispanic men 1.19 (1.00−1.42) 1.17 (0.96−1.42) Case mix 0.5 1.0 2.0 Case mix + hospital (RE) Case mix + hospital (FE) Less ICU More ICU OR (95% CI) Thepointestimatesand95percentconfidenceintervalsrepresenttheratiooftheodds of ICU serviceuse during the terminal admission among each race/ethnicity group comparedtowhitewomenusingthreestatisticalmodels:amodeladjustingfordemo- graphics,insurancestatus,admissiontype,andchronicconditions(casemix),andtwo models that additionally adjust for the clustering of patients withinhospitals,one of whichtreatsthehospitalasarandomeffect(RE),andoneofwhichtreatsthehospitalas a fixed effect (FE). For both black and Hispanic patients, the added adjustment for hospitaleffect,regardlessofspecification,decreasedtheoddsratioofICUusecom- paredtowhitewomen.Themagnitudeofthechangeinthepointestimateforblacks andHispanicssuggeststhatthemajorityofobserveddifferencesinterminalICUuse were due to between-hospital differences in ICU use and not within-hospital differ- encesinICUusebyrace/ethnicity. 2228 HSR:HealthServicesResearch41:6(December2006) words,adultsofvaryingages,genders,andconditionsarenotconcentratedin some hospitals more than others. Additionally, changes in parameter esti- matesforinsurancestatuswerenotsignificantlydifferentbetweentheunad- justedandadjustedmodels,althoughthechangeintheparameterestimatefor ‘‘uninsured’’approachedstatisticalsignificance.Wereporttheparameteres- timates for each variable included in all models in Tables E1, E2, and E3 availableintheonlinedatasupplementtothisarticle. DISCUSSION AmonghospitaldecedentsinfiveU.S.states,black,Hispanic,andothernon- white patients were more likely to die with ICU services than whites. How- ever, the majority of the difference in ICU use by blacks and Hispanics comparedwithwhitescouldbeexplainedbythedifferentialuseofhospitals withhigherterminalICUadmissionpatternsbytheseminoritypopulations. Thus,themajorityoftheracial/ethnicdifferenceinterminalICUusewasdue tobetween-hospitaldifferencesratherthanwithin-hospitaldifferences.Thisfind- ing emphasizes that race and ethnicity-based treatment differences may be misattributedtounequaltreatmentratherthantodifferentialaccesspatternsif theconfoundingeffectofhospitalisnotaddressed. Thecurrentstudyhasbothstrengthsandlimitations.Itwasbasedona largeanddiversesampleofadultdecedentsintheUnitedStates.Thesample cannot be considered representative, however, as the East was over- represented and states in the South and Southwest with significant minority populationswerenotincluded.Thequalityofraceandethnicityinformation drawnfromhospitaldischargedataisalwaysaconcerninadministrativedata analyses(LaVeist1994).Nonetheless,manysuchstudieshaveinformedU.S. policyonracialandethnicdisparities,andoftenwithoutthebenefitofoneof thisstudy’sstrengths,theuseofstatisticaladjustmentsforprovider-levelclus- tering. Regarding adjustment for provider-level clustering, the use of a FEs model is probably superior to a model that treats hospital as a RE because unobserved hospital characteristics, including treatment patterns, may be correlated with race. However, the findings were qualitatively similar with both model specifications. Another limitation is our inability to distinguish between hospital decedents who died in the ICU and those who died in another unit of the hospital after the use of intensive care. However,for the majority of decedents, hospital LOS was (cid:2) 1 day longer than ICU LOS (Angusetal.2004).Thus,ICUcaredominatedtheirterminaladmission.We

Description: