Bamako sounds: the Afropolitan ethics of Malian music PDF

Preview Bamako sounds: the Afropolitan ethics of Malian music

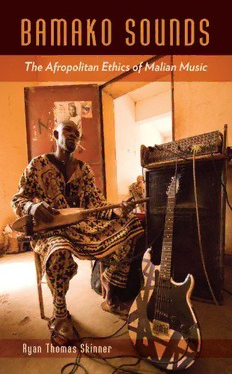

BAMAKO SOUNDS This page intentionally left blank Bamako Sounds . . . . The Afropolitan Ethics of Malian Music Ryan Thomas Skinner A QUADRANT BOOK University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London Quadrant, a joint initiative of the University of Minnesota Press and the Institute for Advanced Study at the University of Minnesota, provides support for interdisciplinary scholarship within a new, more collaborative model of research and publication. http://quadrant.umn.edu. Sponsored by the Quadrant Global Cultures group (advisory board: Evelyn Davidheiser, Michael Gold- man, Helga Leitner, and Margaret Werry), and by the Institute for Global Studies at the University of Minnesota. Quadrant is generously funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Publication of this book was made possible in part by a grant from the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For supplemental audiovisual material, chapter study guides, book reviews, and links to related online resources, visit http://z.umn.edu/bamakosounds. Chapter 5 was originally published as “Money Trouble in an African Art World: Copyright, Piracy, and the Politics of Culture in Postcolonial Mali,” IASPM@Journal 3, no. 1 (2012): 63– 79; reprinted by permission. Copyright 2015 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401-2 520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Skinner, Ryan Thomas, author. Bamako sounds : the Afropolitan ethics of Malian music / Ryan Thomas Skinner. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8166-9349-8 (hc : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8166-9350-4 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Music—Moral and ethical aspects—Mali—Bamako. 2. Music—Moral and ethical aspects— Mali. 3. Musicians—Mali—Bamako—Social conditions. 4. Ethnomusicology—Mali—Bamako. 5. Group identity—Mali—Bamako. 6. Group identity in the performing arts—Mali—Bamako. 7. Mandingo (African people)—Mali—Bamako—Ethnic identity. 8. City and town life—Mali— Bamako. 9. Bamako (Mali)—Social conditions. I. Title. ML3917.M35S55 2015 780.96623—dc23 2014025344 Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal- opportunity educator and employer. 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Introduction: A Sense of Urban Africa 1 1. Representing Bamako 15 2. Artistiya 47 3. Ethics and Aesthetics 77 4. A Pious Poetics of Place 107 5. Money Trouble 131 6. Afropolitan Patriotism 155 Conclusion: An Africanist’s Query 181 Acknowledgments 189 Notes 193 Bibliography 209 Index 227 This page intentionally left blank · INTRODUCTION · A Sense of Urban Africa This book is about the morality and ethics of musical identity and expression in a West African city: Bamako, Mali (Fig- ure 1). Bamako is a city that incorporates multiple scales of place: national, local, translocal, and global. It is Malian, the multiethnic capital of a mod- ern nation- state; Mande, the metropolitan center of a cultural heartland; Muslim, an urban locus of the Islamic Ecumene; and African, a continen- tal city in a postcolonial world.1 Bamako residents encounter these regis- ters of place to varying degrees and in a variety of forms in their everyday lives, but such encounters, in all their diversity, always entail an ethical stance: an active positioning of the self vis- à- vis national, local, trans- local, and global polities. These situated, value- inflected encounters con- stitute what I call an “Afropolitan ethics.” For the group of professional musicians with whom I have worked over of the past fifteen years, such ethical stances are the frequent subject of musical performance and in- terpretation. Music, whether performed live on stage, broadcast on the radio, or streamed over the Internet, is a privileged mode of moral ex- pression in Bamako today. In this book, I present Malian artists and their audiences as a key demographic through which an Afropolitan ethics may be examined and elaborated, exemplifying broader trends in Africa and its diaspora. By employing the term “Afropolitan,” I invoke a perspective on con- temporary African urbanism that acknowledges the worldly orientations of the continent’s peoples and recognizes the prescriptive and volitional moorings that bind individuals to local lifeworlds. In the words of African historian and culture critic Achille Mbembe, Afropolitanism is the awareness of this imbrication of here and elsewhere, the pres- ence of the elsewhere in the here and vice versa, this relativization of roots and primary belongings and a way of embracing, fully cognizant of origins, the foreign, the strange and the distant, this · 1 · 2 INTRODUCTION Figure 1. Mali and West Africa. Map by Philip Schwartzberg, Meridian Mapping, Minneapolis. capacity to recognize oneself in the face of another and to value the traces of the distant within the proximate, to domesticate the un- familiar, to work with all manner of contradictions— it is this cultural sensibility, historical and aesthetic, that suggests the term “Afropolitanism.” (2010, 229) Rejecting the undifferentiated universalism that the term “cosmopolitan” connotes (a critique that I elaborate in the conclusion of this book), Afropolitanism locates Africans’ global routes and local roots within a postcolonial and diasporic geopolitical framework. It represents particular urban African perspectives on the world that respect the specificity of cultural provenance and practice, reflect the common concerns and in- terests of continental and diasporic peoples, and respond to the essential- isms and injustices that continue to provincialize African peoples and in- hibit their access to the international community. Through ethnography, social history, and close listening, this book elaborates the concept of Afropolitanism through the lives and works of Bamako artists. It shows, through thickly described case studies, the social and musical means by which artists reconcile local concerns with global interests and assert INTRODUCTION 3 Figure 2. Sidiki Diabaté in the studio. Photograph by the author. themselves within an uneven postcolonial and diasporic world as ethical Afropolitan subjects. To understand the ethics of Afropolitanism in Bamako, this book ad- dresses multiple modes of self- identification and expression within the individually coherent and collectively co- present moral spheres of urban culture, profession, aesthetics, religion, economy, and politics. Take, for example, the life and work of artist Sidiki Diabaté (Figure 2). Raised in the bustle of Bamako, Sidiki belongs to a renowned clan of Mande “griots,” or jeliw (sing. jeli; the w indicates the plural), musical artisans practicing the time-h onored art of musical panegyric and storytelling known as jeliya (literally, jeli- ness; the ya indicates the abstract noun).2 Within this tradi- tion, Sidiki’s family has performed the kora (a twenty- one- string Mande harp) for generations (see Skinner 2008a; a family history of music to which I return in chapter 3). His grandfather and namesake was a found- ing member of the Ensemble Instrumental National in Mali, and his fa- ther, Toumani, is a Grammy Award–w inning virtuoso on the world music circuit. Sidiki is a devout Muslim and proud of his African roots. In his