Balanchine and the lost muse : revolution and the making of a choreographer PDF

Preview Balanchine and the lost muse : revolution and the making of a choreographer

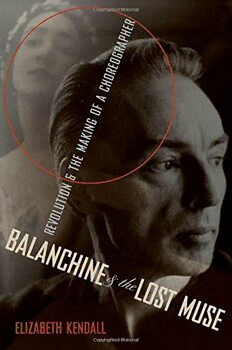

Balanchine an d the Lost Muse B alanchine and the Lost Muse R e v o l u t i o n a n d t h e M a k i n g o f a C h o r e o g r a p h e r Elizabeth Kendall 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Oxford University Press 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitt ed by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction rights outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form, and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kendall, Elizabeth, 1947– Balanchine and the lost muse : revolution and the making of a choreographer / Elizabeth Kendall. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-995934-1 (alk. paper) 1. Balanchine, George. 2. Choreographers—United States—Biography. 3. Ivanova, Lidiia, d.1924. I. Title. GV1785.B32K46 2013 792.8 (cid:1) 2092—dc23 2012042482 Frontispiece: Georges and Lidochka, 1921 Courtesy, Bernard Taper 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Tsiskari Balanchivadze and Keti Machavariani Balanchivadze And in memory of Djarji Balanchivadze , 1941–2011 Pianist, composer, painter This page intentionally left blank Contents ix Preface · xii Acknowledgments · xiv Cast of Characters · 3 Introduction · 13 One Maria and Meliton · 25 Two Georgi · 41 Three Th eater School: Boys · 57 Four Lidochka · 69 Five Th eater School: Girls · 95 Six 1917 · 113 Seven Th eater School: Th e Hungry Years · 145 Eight Th e NEP Economy · 173 Nine Th e Young Ballet · 189 Ten Th e Last Year, Summer to Summer · 217 Eleven Death and Life · 245 A Note on Sources · 246 Notes · 265 Bibliography · 269 Index · Balanchine BALANCHINE Is a Trademark of Th e George Balanchine Trust. Courtesy of New York City Ballet Archives, Ballet Society Collection. Preface Th is book had its beginnings in two revelatory moments. Th e fi rst came in 1981 when I interviewed George Balanchine, founder of the New York City Ballet and virtual inventor of ballet in America, in his offi ce in Lincoln Center’s New York State Th eater. I was a young dance critic sent by the Ford Foundation. He was seventy-seven, slim and dapper, white hair brushed back from a high forehead. “Is boring, questions we must talk about,” said Balanchine as he rose to meet me. I agreed and prepared to leave—I had no right to his time. “So, we do questions, then we talk,” he said briskly but mischievously. Indeed, aft er we discussed Foundation business he began telling me tales about his life back in 1920s revolutionary Petrograd, maybe because he liked young women: tales about starving, and sewing saddles and playing batt ered pianos in movie houses just to get food. How far away—like the distance to a star—was this past from the complacent America where we sat now. I put myself in his shoes, and as him despaired of conveying the real nature of his youthful experience. My patchy Russian history was causing him to serve up traumatic memories as careful fairy tales. I’d fallen in love with Balanchine’s company, the New York City Ballet, right aft er I’d arrived in New York in 1973. Actually, “falling in love” isn’t right. I’d come to write about avant-garde modern dance; I’d sampled the whole dance scene, and I’d fallen i nto the New York City Ballet. I’d found myself responding to City Ballet’s dancing with emotions almost religious in nature: exaltation, wonder, and a sharp gratitude for the beauty and longing being enacted onstage, especially by the ballerinas. Th is was a time when all the young women I knew were waking up to feminism. Where in our culture were the spaces, the works of art, where women’s inner lives could be explored and dramatized?