Babaylan: Feminist Articulations and Expressions PDF

Preview Babaylan: Feminist Articulations and Expressions

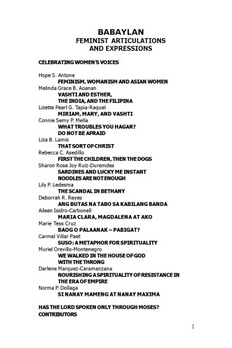

BABAYLAN FEMINIST ARTICULATIONS AND EXPRESSIONS CELEBRATING WOMEN’S VOICES Hope S. Antone FEMINISM, WOMANISM AND ASIAN WOMEN Melinda Grace B. Aoanan VASHTI AND ESTHER, THE INDIA, AND THE FILIPINA Lizette Pearl G. Tapia-Raquel MIRIAM, MARY, AND VASHTI Connie Semy P. Mella WHAT TROUBLES YOU HAGAR? DO NOT BE AFRAID Liza B. Lamis THAT SORT OF CHRIST Rebecca C. Asedillo FIRST THE CHILDREN, THEN THE DOGS Sharon Rose Joy Ruiz-Duremdes SARDINES AND LUCKY ME INSTANT NOODLES ARE NOT ENOUGH Lily P. Ledesma THE SCANDAL IN BETHANY Deborrah R. Reyes ANG BUTAS NA TABO SA KABILANG BANDA Aileen Isidro-Carbonell MARIA CLARA, MAGDALENA AT AKO Marie Tess Cruz BAOG O PALAANAK – PABIGAT? Carmel Villar Paet SUSO: A METAPHOR FOR SPIRITUALITY Muriel Orevillo-Montenegro WE WALKED IN THE HOUSE OF GOD WITH THE THRONG Darlene Marquez-Caramanzana NOURISHING A SPIRITUALITY OF RESISTANCE IN THE ERA OF EMPIRE Norma P. Dollaga SI NANAY MAMENG AT NANAY MAXIMA HAS THE LORD SPOKEN ONLY THROUGH MOSES? CONTRIBUTORS 1 THE UNION SEMINARY BULLETIN Occasional Papers of the Faculty of Union Theological Seminary January 2007 Year Two Volume 1 Seminaries and divinity schools have, for years, been described as marketplaces of ideas. Unfortunately, many such institutions have been marketplaces, or more appropriately, malls of Western ideas. In other words, if one were to go “shopping” in these “malls” of theological education, one will be amazed by the number of stalls, stores and shops offering “imported” goods: from theologies, to liturgies, to libraries, to models of hermeneutics. We need more “shops” that proudly offer the diversity of Filipino and Asian articulations of faith. This collection is an attempt at doing just that. Revelation E. Velunta, GENERAL EDITOR BABAYLAN: FEMINIST ARTICULATIONS AND EXPRESSIONS Lizette Pearl G. Tapia-Raquel Volume Editor ©2007 The Union Seminary Bulletin The Union Seminary Bulletin publishes sermons, lectures, and other works by the Union Theological Seminary faculty and presentations by guests. We do not accept unsolicited material. Please address correspondence to The Union Seminary Bulletin, UTS Campus, Dasmarinas 4114 Cavite, Philippines, e-mail [email protected]. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CELEBRATING WOMEN’S VOICES 4 Hope S. Antone FEMINISM, WOMANISM AND ASIAN WOMEN 7 Melinda Grace B. Aoanan VASHTI AND ESTHER, THE INDIA, AND THE FILIPINA 31 Lizette Pearl G. Tapia-Raquel MIRIAM, MARY, AND VASHTI 44 Connie Semy P. Mella WHAT TROUBLES YOU HAGAR? DO NOT BE AFRAID 54 Liza B. Lamis THAT SORT OF CHRIST 92 Rebecca C. Asedillo FIRST THE CHILDREN, THEN THE DOGS 100 Sharon Rose Joy Ruiz-Duremdes SARDINES AND LUCKY ME INSTANT NOODLES ARE NOT ENOUGH 106 Lily P. Ledesma THE SCANDAL IN BETHANY 110 Deborrah R. Reyes ANG BUTAS NA TABO SA KABILANG BANDA 117 Aileen Isidro-Carbonell MARIA CLARA, MAGDALENA AT AKO 139 Marie Tess Cruz BAOG O PALAANAK – PABIGAT? 148 Carmel Villar Paet SUSO: A METAPHOR FOR SPIRITUALITY 155 Muriel Orevillo-Montenegro WE WALKED IN THE HOUSE OF GOD WITH THE THRONG 161 Darlene Marquez-Caramanzana NOURISHING A SPIRITUALITY OF RESISTANCE IN THE ERA OF EMPIRE 167 Norma P. Dollaga SI NANAY MAMENG AT NANAY MAXIMA 175 HAS THE LORD SPOKEN ONLY THROUGH MOSES? 183 CONTRIBUTORS 203 3 CELEBRATING WOMEN’S VOICES There is always more than one way of telling a story. On the shores of Mactan stand two markers that memorialize April 27, 1521. The first one, erected in 1941, reads: “On this spot Ferdinand Magellan died on April 27, 1521 wounded in an encounter with the soldiers of Lapulapu, chief of Mactan Island. One of Magellan’s ships, the Victoria, under the command of Juan Sebastian Elcano, sailed from Cebu on May 1, 1521, and anchored at San Lucar de Barrameda on September 6, 1522, thus completing the first circumnavigation of the earth.” The second one, put up in 1951, reads: “Here, on April 27 1521, Lapulapu and his warriors repulsed the Spanish invaders, killing their leader, Ferdinand Magellan. Thus, Lapulapu became the first Filipino to have repelled European aggression.” Actually, as this anthology of diverse articulations and expressions shows, there is really more than one way, there is actually legion. Hope S. Antone’s “Feminism, Womanism, and Asian Women” serves as an excellent introductory essay to the diversity, plurality, and possibilities of women-centered discourses. In their articles seven of the contributors explore unfamiliar ways of reading very familiar biblical passages. Melinda Grace B. Aoanan’s “Vashti and Esther, the India, and the Filipina” juxtapositions Vashti’s open defiance with Esther’s underground resistance. Lizette Pearl G. Tapia-Raquel’s “Miriam, Mary, and Vashti” critiques the systemic marginalization of three women prophets. Using narrative criticism, Connie Semy P. Mella’s “What Troubles You Hagar? Do Not Be Afraid” pushes the boundaries of God’s “family” to include those we call “unbelievers” and “enemies.” Liza B. Lamis’ “That Sort of Christ” takes two texts—the Canaanite Woman of Matthew 15:21-28 and the struggles of Erlinda, a 4 struggling mother—in a conversation with Jesus. Rebecca C. Asedillo’s “First the Children, then the Dogs” takes the same Matthean text and its Markan parallel to argue for a reading where Jesus is “caught with his compassion down.” Sharon Rose Joy Ruiz-Duremdes’ “Sardines and Lucky Me Instant Noodles Are Not Enough” challenges the traditional reading of the Parable of the Sheep and the Goats. She argues that food, water, and security are nothing when people are not free. Lily P. Ledesma’s “The Scandal in Bethany,” unlike many feminists, makes a case in favor of Mary, instead of Martha in the Lukan periscope of Jesus’ visit to the sisters. Mary, for Lily, broke all conventions by doing the opposite of what all good women should do. Deborrah R. Reyes’ “Ang Butas Na Tabo Sa Kabilang Banda” introduces the “tabo” (dipper) as an interpretive or hermeneutical lens. Through the “tabo” Reyes critically engages imperial discourses, especially as it pertains to women and womanhood. Aileen Isidro-Carbonell’s “Maria Clara, Magdalena At Ako” challenges the boxes or molds patriarchy created especially for women in the Philippines—Maria Clara and Magdalena, both of which are limited and limiting. Aileen challenges women to break free from these molds. Marie Tess Cruz’s “Baog O Palaanak – Pabigat?” engages Yahweh and Jesus in a poetic conversation on the “curse” of barrenness and the “blessing” of fertility. Carmel Villar Paet’s “Suso: A Metaphor for Spirituality” explores the sacredness of breasts and calls for the de-objectification of the same. Muriel Orevillo-Montenegro’s “We Walked in the House of God with the Throng” takes the plight of abused women and children and challenges the notion of churches and Christian homes as places of safety. Darlene Marquez-Caramanzana’s “Nourishing A Spirituality Of Resistance In The Era Of Empire” challenges her 5 readers to take up the “spirituality of resistance” against the juggernaut of empire. Norma P. Dollaga’s “Si Nanay Mameng At Nanay Maxima” explores the need for militancy in the quest for justice, especially among society’s “widows.” She engages the Parable of the Widow and the Judge through the struggles of Nanay Mameng and Nanay Maxima. If there is any thread that binds these diverse articulations and expressions together, I think it is found in each article’s commitment to the voiceless and to other voices—wherever you find them: in the margins of our Bible stories, hidden in the dark closets of our homes, churches, and institutions, or outside the high walls our comfortable societies have created to shut others out. In a country whose traditions are both pluri-form and multi-vocal, these fifteen women are among the many who have faith stories to share. And there are many, many more whose stories of faith are yet to be shared. This collection is an open invitation to start sharing… Revelation E. Velunta 31 January 2007 6 FEMINISM, WOMANISM AND ASIAN WOMEN By. Hope S. Antone Hope S. Antone Since the popularization of “womanist theology” many Asian women who are doing feminist theology have been challenged to define who they are and what they are doing. Although by popular use and for lack of a common Asian word “Asian feminism” has become the commonly agreed name thus far, there are those who feel uncomfortable using what is deemed to be a Western construct just as there are many who think the whole feminist cause is another foreign movement encroaching on Asian soil. There are also those who desire a clean break from the traditional concept of “feminine” that for so long molded the “true and virtuous woman” as soft spoken, submissive, slow to anger and action, and dependent. Therefore, some Asian women prefer to simply call their new interest as “women’s issues” and their new commitment and perspective as “women doing theology.” With the popularization of “womanist” perspective and “womanist theology,” some Asian women have been quick to identify with the reference, “women of color.” But as in their experience with “feminism,” there are also those who are cautious about adopting the name “womanist” and the description “women of color” for themselves and for what they are doing. I believe that Asian Christian feminism1 has so much to learn from womanism but it still has to grapple with what is unique about itself in view of its context, the needs of its constituencies, and the emerging political-economic and religious-cultural realities. This paper describes an Asian woman’s gleanings from feminism and womanism with the hope that some ties may be found and some links made to hopefully enrich our women’s theologizing in Asia. The paper will consist of two parts. The first part will trace the historical development of womanist 7 theology, highlighting its living praxis of shared experience, shared theology, shared leadership and shared naming. This will naturally make a comparison with the earlier movement of feminism. The second part will try to find ties and parallels as well as challenges for Asian feminism. Beginnings of Womanist Theology African American women doing womanist theology trace the history of the field to the mid-1970s. However, they acknowledge two earlier movements in America which led to the emergence of a distinctively African American women’s consciousness: feminism and black power movement.2 Perhaps, a third movement could also be named which helped to sharpen black women’s critique and articulation of their multiple oppression: the black women’s club movement.3 One strong battle cry of 19th century feminism in America was the women’s fight for their right to vote. American women, mostly white, who realized that they could do more than play the role imposed on them, began to resist the old ideal of Victorian womanhood: domesticated, submissive, dependent - in relation to their husbands. The feminist consciousness of American women opened the struggle for recognition of their worth and untapped potential as well as the assertion of their inherent equality in human dignity with men. African American women were part of this struggle for women’s social, economic and political rights. However, a number of them felt that the feminist call for women’s rights did not cross the racial barriers that remained between white and black women. There was no interest in eliminating the racial discrimination still prevailing within the women’s movement. The African American women felt that American feminism was simply not only 8 inadequate but also inappropriate. It was evidently white and consequently racist.4 Although black and white women did share a subordinate position in society, black women still had a much lower position, whereas white women had more privileges and were often in a position to abuse black women. Such a privileged position of white women is rooted in the historical gulf between the whites and the blacks: white women were daughters and granddaughters of slaveholders while black women were daughters and granddaughters of slaves. The rise of the black power movement in the 1960s highlighted the racial dimension of the African American people’s struggle for equality. It openly challenged racism so imbedded in the structures of church and society and the mindset of the people. Black women were again very active in this struggle, but often as the “unsung” leaders and heroines behind the prominent male leaders of the movement. Yet, it was not just for this lack of recognition that they realized the sexism within the black community. There was the outright and outspoken devaluing of their potential both in the church and the community simply because of their gender. It was clear that while both African American men and women shared the subordinate position in society in relation to white people, black men took advantage of their male privilege over black women, a privilege from patriarchal society. Apart from the dimensions of race and gender, African American women also realized that there was an economic and class dimension to their oppression. Social mobility and social stratification due to more education, better profession and higher income helped to reinforce the existing structure of inequality not only between blacks and whites in America but even between blacks within the black community.5 It has generated 9 competitive class consciousness and individualism so destructive to the building of a community which is based on cohesiveness and social responsibility. Black women’s growing consciousness of their multi-dimensional oppression (because of race-gender-class factors) found expression and sharpening in the black women’s club movement. While the white women’s club movement promoted activism outside the home and moral values expressed in the concepts of “virtuous womanhood” and “educated motherhood,” the black women’s club movement addressed more economic, political and ethical issues.6 While black and white women shared the burden of subordination due to gender, they were different not only because of their races, but because of their socio-historical and economic realities. Hence, “the formation of a separate black women’s club movement was more than a defensive reaction because of racist exclusion; it was an act of self-determination to address the particular concerns of black women and all black people.”7 Although there were diverse types of groups within the black women’s club movement, they all could be described as a socio-religious movement against race, gender and class oppression that was also concerned about the advancement of all black people.8 It was a social movement because it was a national network of African American women, a public venue for challenging power relations. It was also a religious movement because these black women were actively involved in the church, were often trained in the church, and some local member clubs were church groups themselves. The term “womanist” as applied to the black women’s living praxis is a much later development compared to the rise of the three movements mentioned earlier. But the roots of “womanist” consciousness go back to the 10