Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach PDF

Preview Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach

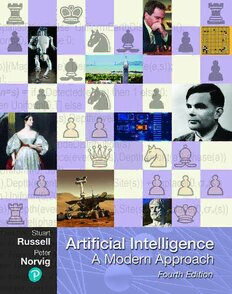

ForLoy, Gordon,Lucy, George, andIsaac—S.J.R. ForKris,Isabella,and Juliet— P.N. Preface Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a big field, and this is a big book. We have tried to explore thefullbreadthofthefield,whichencompasseslogic,probability, andcontinuousmathemat- ics; perception, reasoning, learning, and action; fairness, trust, social good, and safety; and applications that range from microelectronic devices torobotic planetary explorers to online services withbillionsofusers. The subtitle of this book is “A Modern Approach.” That means we have chosen to tell the story from a current perspective. We synthesize what is now known into a common framework, recasting early work using the ideas and terminology that are prevalent today. Weapologize tothosewhosesubfieldsare,asaresult,lessrecognizable. New to this edition Thisedition reflectsthechangesinAIsincethelasteditionin2010: • We focus more on machine learning rather than hand-crafted knowledge engineering, duetotheincreased availability ofdata,computing resources, andnewalgorithms. • Deep learning, probabilistic programming, and multiagent systems receive expanded coverage,eachwiththeirownchapter. • The coverage of natural language understanding, robotics, and computer vision has beenrevisedtoreflecttheimpactofdeeplearning. • Theroboticschapternowincludes robotsthatinteractwithhumansandtheapplication ofreinforcement learningtorobotics. • PreviouslywedefinedthegoalofAIascreating systemsthattrytomaximizeexpected utility,wherethespecificutilityinformation—the objective—is suppliedbythehuman designersofthesystem. Nowwenolongerassumethattheobjectiveisfixedandknown bytheAIsystem;instead, thesystem maybeuncertain aboutthetrueobjectives ofthe humansonwhosebehalfitoperates. Itmustlearnwhattomaximizeandmustfunction appropriately evenwhileuncertain abouttheobjective. • WeincreasecoverageoftheimpactofAIonsociety,includingthevitalissuesofethics, fairness, trust,andsafety. • We have moved the exercises from the end of each chapter to an online site. This allows usto continuously add to, update, and improve the exercises, tomeet the needs ofinstructors andtoreflectadvances inthefieldandinAI-relatedsoftwaretools. • Overall, about 25% of the material in the book is brand new. The remaining 75% has beenlargelyrewrittentopresentamoreunifiedpictureofthefield. 22%ofthecitations inthiseditionaretoworkspublished after2010. Overview of the book The main unifying theme is the idea of an intelligent agent. We define AI as the study of agents that receive percepts from the environment and perform actions. Each such agent implements a function that maps percept sequences to actions, and we cover different ways to represent these functions, such as reactive agents, real-time planners, decision-theoretic vii viii Preface systems, and deep learning systems. We emphasize learning both as a construction method for competent systems and as a way of extending the reach of the designer into unknown environments. We treat robotics and vision not as independently defined problems, but as occurringintheserviceofachievinggoals. Westresstheimportanceofthetaskenvironment indetermining theappropriate agentdesign. Our primary aim is to convey the ideas that have emerged over the past seventy years of AI research and the past two millennia of related work. We have tried to avoid exces- siveformalityinthepresentation oftheseideas,whileretaining precision. Wehaveincluded mathematical formulas and pseudocode algorithms to make the key ideas concrete; mathe- maticalconcepts andnotation aredescribed inAppendix Aandourpseudocode isdescribed inAppendixB. This book is primarily intended for use in an undergraduate course or course sequence. The book has 28 chapters, each requiring about a week’s worth of lectures, so working through the whole book requires a two-semester sequence. A one-semester course can use selected chapters to suit the interests of the instructor and students. The book can also be used in a graduate-level course (perhaps with the addition of some of the primary sources ◮ suggested inthebibliographical notes),orforself-study orasareference. Throughout the book, important points are marked with a triangle icon in the margin. Term Wherever a new term is defined, it is also noted in the margin. Subsequent significant uses oftheterm areinbold, butnotinthemargin. Wehaveincluded acomprehensive index and anextensivebibliography. Theonlyprerequisite isfamiliaritywithbasicconceptsofcomputerscience(algorithms, data structures, complexity) at a sophomore level. Freshman calculus and linear algebra are usefulforsomeofthetopics. Online resources Online resources are available through pearsonhighered.com/cs-resources or at the book’sWebsite,aima.cs.berkeley.edu.Thereyouwillfind: • Exercises,programming projects, andresearch projects. Thesearenolongerattheend of each chapter; they are online only. Within the book, we refer to an online exercise with a name like “Exercise 6.NARY.” Instructions on the Web site allow you to find exercisesbynameorbytopic. • Implementations ofthealgorithmsinthebookinPython,Java,andotherprogramming languages (currently hostedatgithub.com/aimacode). • A list of over 1400 schools that have used the book, many with links to online course materialsandsyllabi. • Supplementary materialandlinksforstudentsandinstructors. • Instructions onhowtoreporterrorsinthebook,inthelikelyeventthatsomeexist. Book cover The cover depicts the final position from the decisive game 6 of the 1997 chess match in whichtheprogramDeepBluedefeatedGarryKasparov(playingBlack),makingthisthefirst time a computer had beaten a world champion in a chess match. Kasparov is shown at the Preface ix top. To his right is a pivotal position from the second game of the historic Go match be- tweenformerworldchampion LeeSedolandDeepMind’s ALPHAGO program. Move37by ALPHAGO violated centuries ofGoorthodoxy and wasimmediately seen by human experts as an embarrassing mistake, but it turned out to be a winning move. At top left is an Atlas humanoid robot built by Boston Dynamics. A depiction of a self-driving car sensing its en- vironment appears between AdaLovelace, theworld’s firstcomputer programmer, andAlan Turing, whose fundamental work defined artificial intelligence. At the bottom of the chess board areaMarsExploration Roverrobot andastatue ofAristotle, whopioneered thestudy oflogic;hisplanningalgorithmfromDeMotuAnimaliumappearsbehindtheauthors’names. BehindthechessboardisaprobabilisticprogrammingmodelusedbytheUNComprehensive Nuclear-Test-BanTreatyOrganizationfordetecting nuclearexplosionsfromseismicsignals. Acknowledgments It takes a global village to make a book. Over 600 people read parts of the book and made suggestions for improvement. Thecomplete list is at aima.cs.berkeley.edu/ack.html; wearegratefultoallofthem. Wehavespaceheretomentiononlyafewespeciallyimportant contributors. Firstthecontributing writers: • JudeaPearl(Section13.5,CausalNetworks); • VikashMansinghka (Section15.3,ProgramsasProbability Models); • MichaelWooldridge (Chapter18,Multiagent DecisionMaking); • IanGoodfellow (Chapter21,DeepLearning); • JacobDevlinandMei-WingChang(Chapter24,DeepLearningforNaturalLanguage); • JitendraMalikandDavidForsyth(Chapter25,ComputerVision); • AncaDragan(Chapter26,Robotics). Thensomekeyroles: • CynthiaYeungandMalikaCantor(projectmanagement); • JulieSussmanandTomGalloway(copyediting andwritingsuggestions); • OmariStephens(illustrations); • TracyJohnson(editor); • ErinAultandRoseKernan(coverandcolorconversion); • Nalin Chhibber, Sam Goto, Raymond de Lacaze, Ravi Mohan, Ciaran O’Reilly, Amit Patel,DragomirRadiv,andSamagraSharma(onlinecodedevelopmentandmentoring); • GoogleSummerofCodestudents (onlinecodedevelopment). Stuartwouldliketothankhiswife,LoySheflott,forherendlesspatienceandboundless wisdom. He hopes that Gordon, Lucy, George, and Isaac will soon be reading this book after they have forgiven him for working so long on it. RUGS (Russell’s Unusual Group of Students)havebeenunusually helpful, asalways. Peter would like to thank his parents (Torsten and Gerda) for getting him started, and hiswife(Kris),children(BellaandJuliet), colleagues, boss, andfriendsforencouraging and tolerating himthrough thelonghoursofwritingandrewriting. About the Authors Stuart Russell was born in 1962 in Portsmouth, England. He received his B.A. with first- class honours inphysics fromOxfordUniversity in1982, andhisPh.D.incomputer science from Stanford in 1986. He then joined the faculty of the University of California at Berke- ley, where he is aprofessor and former chair of computer science, director of the Center for Human-Compatible AI, and holder of the Smith–Zadeh Chair in Engineering. In 1990, he received thePresidential YoungInvestigator AwardoftheNational Science Foundation, and in1995hewascowinneroftheComputersandThoughtAward. HeisaFellowoftheAmer- ican Association for Artificial Intelligence, the Association for Computing Machinery, and theAmericanAssociation fortheAdvancement ofScience, anHonorary FellowofWadham College, Oxford, andan AndrewCarnegie Fellow. Heheld theChaire BlaisePascal inParis from 2012 to 2014. He has published over 300 papers on a wide range of topics in artificial intelligence. His other books include The Use of Knowledge in Analogy and Induction, Do theRightThing: Studies inLimitedRationality (withEricWefald), andHumanCompatible: ArtificialIntelligence andtheProblemofControl. Peter Norvig is currently a Director of Research at Google, Inc., and was previously the director responsible for the core Web search algorithms. He co-taught an online AI class thatsignedup160,000students, helpingtokickoffthecurrentroundofmassiveopenonline classes. HewasheadoftheComputationalSciencesDivisionatNASAAmesResearchCen- ter, overseeing research and development in artificial intelligence and robotics. He received aB.S.inapplied mathematics fromBrownUniversity andaPh.D.incomputer science from Berkeley. He has been a professor at the University of Southern California and a faculty memberatBerkeleyand Stanford. HeisaFellowoftheAmerican Association forArtificial Intelligence, the Association forComputing Machinery, theAmerican AcademyofArtsand Sciences, andtheCalifornia AcademyofScience. Hisother booksareParadigmsofAIPro- gramming: CaseStudiesinCommonLisp,Verbmobil: ATranslationSystemforFace-to-Face Dialog,andIntelligent HelpSystemsforUNIX. Thetwoauthors sharedtheinaugural AAAI/EAAIOutstanding Educatorawardin2016. x Contents I Artificial Intelligence 1 Introduction 1 1.1 WhatIsAI? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 1.2 TheFoundations ofArtificialIntelligence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 1.3 TheHistoryofArtificialIntelligence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17 1.4 TheStateoftheArt . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27 1.5 RisksandBenefitsofAI . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35 2 IntelligentAgents 36 2.1 AgentsandEnvironments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36 2.2 GoodBehavior: TheConceptofRationality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39 2.3 TheNatureofEnvironments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42 2.4 TheStructureofAgents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60 II Problem-solving 3 SolvingProblemsbySearching 63 3.1 Problem-Solving Agents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63 3.2 ExampleProblems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66 3.3 SearchAlgorithms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71 3.4 UninformedSearchStrategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 76 3.5 Informed(Heuristic)SearchStrategies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 84 3.6 HeuristicFunctions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 97 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 104 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106 4 SearchinComplexEnvironments 110 4.1 LocalSearchandOptimizationProblems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110 4.2 LocalSearchinContinuous Spaces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 119 4.3 SearchwithNondeterministic Actions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 122 4.4 SearchinPartiallyObservableEnvironments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 126 4.5 OnlineSearchAgentsandUnknownEnvironments . . . . . . . . . . . . 134 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 141 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142 5 Adversarial SearchandGames 146 5.1 GameTheory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 146 5.2 OptimalDecisionsinGames . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 148 xi xii Contents 5.3 HeuristicAlpha–BetaTreeSearch . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 156 5.4 MonteCarloTreeSearch . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 161 5.5 StochasticGames . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 164 5.6 PartiallyObservable Games . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 168 5.7 LimitationsofGameSearchAlgorithms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 174 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 175 6 ConstraintSatisfaction Problems 180 6.1 DefiningConstraintSatisfaction Problems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 180 6.2 Constraint Propagation: Inference inCSPs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 185 6.3 Backtracking SearchforCSPs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 191 6.4 LocalSearchforCSPs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 197 6.5 TheStructureofProblems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 199 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 203 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 204 III Knowledge, reasoning, andplanning 7 LogicalAgents 208 7.1 Knowledge-Based Agents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 209 7.2 TheWumpusWorld . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 210 7.3 Logic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 214 7.4 Propositional Logic: AVerySimpleLogic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 217 7.5 Propositional TheoremProving . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 222 7.6 EffectivePropositional ModelChecking . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 232 7.7 AgentsBasedonPropositional Logic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 237 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 246 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 247 8 First-OrderLogic 251 8.1 Representation Revisited . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 251 8.2 SyntaxandSemanticsofFirst-OrderLogic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 256 8.3 UsingFirst-OrderLogic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 265 8.4 KnowledgeEngineering inFirst-OrderLogic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 271 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 277 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 278 9 InferenceinFirst-OrderLogic 280 9.1 Propositional vs.First-OrderInference . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 280 9.2 UnificationandFirst-OrderInference . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 282 9.3 ForwardChaining . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 286 9.4 BackwardChaining . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 293 9.5 Resolution . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 298 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 309 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 310 Contents xiii 10 KnowledgeRepresentation 314 10.1 Ontological Engineering . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 314 10.2 CategoriesandObjects . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 317 10.3 Events . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 322 10.4 MentalObjectsandModalLogic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 326 10.5 ReasoningSystemsforCategories . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 329 10.6 ReasoningwithDefaultInformation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 333 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 337 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 338 11 AutomatedPlanning 344 11.1 DefinitionofClassicalPlanning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 344 11.2 AlgorithmsforClassicalPlanning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 348 11.3 HeuristicsforPlanning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 353 11.4 Hierarchical Planning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 356 11.5 PlanningandActinginNondeterministic Domains . . . . . . . . . . . . . 365 11.6 Time,Schedules, andResources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 374 11.7 AnalysisofPlanningApproaches . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 378 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 379 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 380 IV Uncertain knowledge and reasoning 12 QuantifyingUncertainty 385 12.1 ActingunderUncertainty . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 385 12.2 BasicProbabilityNotation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 388 12.3 Inference UsingFullJointDistributions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 395 12.4 Independence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 397 12.5 Bayes’RuleandItsUse . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 399 12.6 NaiveBayesModels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 402 12.7 TheWumpusWorldRevisited . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 404 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 407 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 408 13 ProbabilisticReasoning 412 13.1 Representing KnowledgeinanUncertainDomain . . . . . . . . . . . . . 412 13.2 TheSemanticsofBayesianNetworks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 414 13.3 ExactInference inBayesianNetworks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 427 13.4 ApproximateInference forBayesianNetworks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 435 13.5 CausalNetworks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 449 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 453 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 454 14 ProbabilisticReasoningoverTime 461 14.1 TimeandUncertainty . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 461 14.2 Inference inTemporalModels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 465 xiv Contents 14.3 HiddenMarkovModels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 473 14.4 KalmanFilters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 479 14.5 DynamicBayesianNetworks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 485 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 496 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 497 15 Probabilistic Programming 500 15.1 RelationalProbability Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 501 15.2 Open-UniverseProbability Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 507 15.3 KeepingTrackofaComplexWorld . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 514 15.4 ProgramsasProbabilityModels . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 519 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 523 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 524 16 MakingSimpleDecisions 528 16.1 CombiningBeliefsandDesiresunderUncertainty . . . . . . . . . . . . . 528 16.2 TheBasisofUtilityTheory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 529 16.3 UtilityFunctions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 532 16.4 Multiattribute UtilityFunctions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 540 16.5 DecisionNetworks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 544 16.6 TheValueofInformation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 547 16.7 UnknownPreferences . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 553 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 557 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 557 17 MakingComplexDecisions 562 17.1 Sequential DecisionProblems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 562 17.2 AlgorithmsforMDPs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 572 17.3 BanditProblems . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 581 17.4 PartiallyObservable MDPs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 588 17.5 AlgorithmsforSolvingPOMDPs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 590 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 595 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 596 18 MultiagentDecisionMaking 599 18.1 PropertiesofMultiagent Environments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 599 18.2 Non-Cooperative GameTheory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 605 18.3 CooperativeGameTheory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 626 18.4 MakingCollectiveDecisions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 632 Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 645 Bibliographical andHistoricalNotes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 646 V MachineLearning 19 LearningfromExamples 651 19.1 FormsofLearning . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 651