Archaic Period Chronology in the Hill Country of Southern Indiana PDF

Preview Archaic Period Chronology in the Hill Country of Southern Indiana

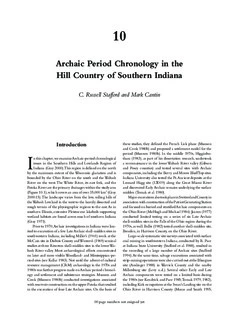

10 Archaic Period Chronology in the Hill Country of Southern Indiana C. Russell Stafford and Mark Cantin Introduction these studies, they defined the French Lick phase (Munson and Cook 1980b) and proposed a settlement model for the period (Munson 1980b). In the middle 1970s, Higginbo- I n this chapter, we examine Archaic-period chronological tham (1983), as part of his dissertation research, undertook issues in the Southern Hills and Lowlands Region of a reconnaissance in the lower Wabash River valley (Gibson Indiana (Gray 2000). This region is defined on the north and Posey counties) and tested several sites with Archaic by the maximum extent of the Wisconsin glaciation and is components, including the Berry and Moore Bluff Top sites. bounded by the Ohio River on the south and the Wabash Indiana University also tested the Ft. Ancient deposits at the River on the west. The White River, its east fork, and the Leonard Hagg site (12D19) along the Great Miami River Patoka River are the primary drainages within the study area and discovered Early Archaic remains underlying the surface (Figure 10.1), which covers an area of over 35,000 km2 (Gray midden (Tomak et al. 1980). 2000:15). The landscape varies from the low, rolling hills of Major excavations also took place in Switzerland County in the Wabash Lowland in the west to the heavily dissected and association with construction of the Patriot Generating Station rough terrain of the physiographic regions to the east. As in and focused on buried and stratified Archaic components on southern Illinois, extensive Pleistocene lakebeds supporting the Ohio River (McHugh and Michael 1984). Janzen (1977) wetland habitats are found across much of southern Indiana conducted limited testing on a series of six Late Archaic (Gray 1971). shell-midden sites in the Falls of the Ohio region during the Prior to 1970, Archaic investigations in Indiana were lim- 1970s, as well. Bellis (1982) tested another shell-midden site, ited to excavation of a few Late Archaic shell-midden sites in Breeden, in Harrison County, on the Ohio River. southwestern Indiana, including Miller’s (1941) work at the Large-scale systematic site surveys associated with surface McCain site in Dubois County and Winters’s (1969) seminal coal mining in southwestern Indiana, conducted by R. Pace studies at three Riverton shell-midden sites in the lower Wa- at Indiana State University (Stafford et al. 1988), resulted in bash River valley. Most archaeological efforts concentrated the recording of a large number of Archaic sites (Stafford on later and more visible Woodland- and Mississippian-pe- 1994). At the same time, salvage excavations associated with riod sites (see Kellar 1983). Not until the advent of cultural strip-mining operations were also carried out at the Bluegrass resource management (CRM) archaeology in the 1970s and site (Anslinger 1988) in Warrick County and the nearby 1980s was further progress made on Archaic period chronol- Millersburg site (Levy n.d.). Several other Early and Late ogy and settlement and subsistence strategies. Munson and Archaic components were tested on a limited basis during Cook (Munson 1980b) conducted investigations associated the 1980s (see Kendrick and Pace 1985; Tomak 1979, 1982), with reservoir construction on the upper Patoka that resulted including Kirk occupations at the Swan’s Landing site on the in the excavation of four Late Archaic sites. On the basis of Ohio River in Harrison County (Mocas and Smith 1995; 00 page numbers not assigned yet 2 C. Russell Stafford and Mark Cantin WAYNE HANCOCK VERMILLION PARKE HENDRICKS MARION Morton PUTNAM RUSH FAYETTE UNION SHELBY Howell MORGAN JOHNSON VIGO CLAY OWEN SchershelOliver VineyardWisconsinGlacialBoundary DECATUR FRANWKhLitIeNwaterR. BROWN BARTHOLOMEW MONROE DEARBORNGreendale Paynetown Light Wint RIPLEY SULLIVAN Riverton GREENE JENNINGS Swan Island W.Fork White R. LAWRENCE JACKSON SWITZEORHLIAONPDatriot Robeson Hill JEFFERSON WabashR. KNOXJerger DAVMIEcCSSain MARTE.INForkWhite RO.RANGBEono WASHINGTON SCOTT CLARK R. Turpin Patoka Lake Sites 12Cl158 Ohio Berry PatokaR.PIKE Amini DUBOIS Moore Bluff Top GIBSON FLOYD CRAWFORD ReidPaddy’s West HARRISON Bluegrass Millersburg Breeden Caesars Swan’s Landing VANDERBURGH WARRICK PERRYMogan Buck Ck 0 20 40 POSEY SPENCERPe929 Crib Md Kilometers Figure 10.1. Archaic site locations in southern Indiana. Smith 1986). The results of much of the work from this pe- an updated chronological assessment for the southern part riod are reported in the gray literature or are not otherwise of the state. Our focus is exclusively on radiocarbon-dated readily available. components and associated diagnostic point forms. When pos- In the late 1990s, major excavations at a series of four sites sible, we also examine stratigraphic sequences at buried sites. with extensive buried Archaic occupations were conducted for Moreover, we focus on changing frequencies of point styles more than 39 months at the Caesars Archaeological Project in time and space since, from our experience, few examples (CAP), located below the Falls of the Ohio (Stafford 2004). can be found of single types defining phases. Initial results are reported in this chapter, although analysis The CAP is located in Knob Creek bottom 10 km of these data is still ongoing. downriver from the Falls of the Ohio in Harrison County, Despite a substantial quantity of fieldwork on Archaic Indiana (Figure 10.1). Extensive excavations of stratified sites in southern Indiana since 1970, the work of Winters components, along with more than 70 radiocarbon dates (1969) on Riverton and of Munson and Cook (1980b) on spanning most of the Holocene, has resulted in a baseline the French Lick phase more than 20 years ago still provides Archaic record for the lower Ohio River valley region (see the only formalized chronological framework for the Archaic Stafford 2004). The project also encompasses two poorly un- period. If further advances are to take place in subsistence derstood Archaic periods in the early (9000–10,000 RCyBP) and settlement (Munson 1980b; Stafford 1994; Stafford et and middle (6000–7500 RCyBP) Holocene. The CAP has al. 2000) and chert use (Cantin 2000; Munson and Mun- yielded, in most cases, large samples of diagnostic artifacts in son 1984) modeling in this region, a more comprehensive association with multiple radiocarbon determinations (Table Archaic chronology needs to be in place. On the basis of 10.1). Excavation data from other sites in the lower Ohio recent investigations conducted as part of the CAP and other Valley provide supplemental support or fill gaps in the CAP CRM-based studies, we attempt in this chapter to provide stratigraphic record. Archaic Period Chronology in the Hill Country of Southern Indiana 3 Table 10.1. Caesars Archaeological Project Archaic Radiocarbon Ages. Cal BC Lab No. Site Phase RCyBP S.D. 1 Sigma Beta-152942 12Hr520 Early Side Notched 10,370 190 10,880–9880 ISGS-4898 12Hr520 Early Side Notched 10,100 100 9997–9390 ISGS-4835 12Hr520 Early Side Notched 10,090 120 9966–9311 ISGS-4797 12Hr520 Early Side Notched 10,050 100 9966–9311 Beta-13574 12Hr520 Early Side Notched 10,020 100 9600–9260 ISGS-4897 12Hr520 Early Side Notched 9700 100 9249–8863 Beta-152586 12Hr520 Early Side Notched 9680 170 9270–8780 Beta-153512 12Hr520 Thebes cluster 9490 60 9140–8620 ISGS-4837 12Hr520 Kirk Corner Notched cluster 9420 100 9088–8555 ISGS-4834 12Hr520 Kirk Corner Notched cluster 9350 80 8736–8478 ISGS-5046 12Hr520 Kirk Corner Notched cluster 8900 120 8260–7827 ISGS-5040 12Hr520 Kirk Corner Notched cluster 8810 120 8203–7652 ISGS-5035 12Hr520 Kirk Corner Notched cluster 8780 80 8159–7655 ISGS-4838 12Hr520 Kirk Corner Notched cluster 8740 100 8156–7602 ISGS-5032 12Hr520 Upper Kirk zone 8320 80 7520–7196 ISGS-4955 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 7220 70 6199–6009 ISGS-4954 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 7220 70 6199–6009 ISGS-4953 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 7110 80 6052–5891 ISGS-4980 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 7170 70 6156–5928 Oxford A-0265 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 6942 60 5873–5730 Oxford A-0264 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 6872 56 5798–5714 ISGS-4981 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 6840 70 5773–5643 ISGS-4996 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 6780 80 5729–5623 ISGS-4994 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 6740 90 5722–5561 ISGS-4960 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 6730 80 5712–5562 Beta-115654 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 6700 70 5610–5520 ISGS-4973 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 6670 70 5657–5529 ISGS-4995 12Hr484 Knob Ck complex 6270 70 5316–5082 Beta-113983 12Hr484 late Middle Archaic 5830 90 4800–4565 ISGS-4956 12Hr484 Riverton 3580 70 2027–1781 ISGS-4957 12Hr484 Riverton 3570 70 2021–1777 Beta-192410 12Hr484 Riverton 3550 40 1943–1778 ISGS-4961 12Hr484 Riverton 3430 70 1876–1638 ISGS-4985 12Hr484 Riverton 3400 70 1767–1618 Beta-115655 12Hr484 Riverton 3140 70 1450–1315 ISGS-4983 12Hr484 Buck Creek Barb 2980 70 1369–1053 ISGS-5025 12Hr481 Stilwell Corner Notched 8360 80 7536–7326 ISGS-5024 12Hr481 early French Lick 5360 70 4326–4046 ISGS-5017 12Hr481 early French Lick 5100 70 3974–3796 ISGS-5020 12Hr481 early French Lick 5020 70 3942–3708 ISGS-5018 12Hr481 early French Lick 4990 70 3935–3672 Beta-106189 12Hr481 late French Lick? 4200 50 2885–2680 In addition to work in the Ohio Valley, we review exten- studies from some 30 Archaic sites in southern Indiana sive excavations at the Bluegrass site as well as more limited (Table 10.2). testing at other Archaic sites over the past 20 years in the We also draw on an extensive 9,011-ha systematic surface interior hill country of southern Indiana to the north. We survey of 21 localities (Data Centers) distributed primarily discuss 82 radiocarbon dates reported in CRM or other across the Wabash Lowlands in southwestern Indiana. More 4 C. Russell Stafford and Mark Cantin Table 10.2. Archaic Radiocarbon Ages from Southern Indiana. Cal BC Lab No. Site Phase RCyBP S.D. 1 Sigma Reference Beta-9458 Bluegrass (12W162) early French Lick 6260 120 5360–5050 this volume Beta-9459 Bluegrass (12W162) early French Lick 5130 80 4040–3800 this volume Beta-33963 Bluegrass (12W162) early French Lick 5030 110 3940–3710 this volume Beta-33964 Bluegrass (12W162) early French Lick 5260 90 4220–3980 this volume Beta-34580 Bluegrass (12W162) early French Lick 5220 90 4220–3960 this volume Beta-34581 Bluegrass (12W162) early French Lick 5290 70 4220–4000 this volume UGa-4708 Bluegrass (12W162) early French Lick 5035 70 3940–3710 this volume Beta-13129 Amini (12Du323) early French Lick 5000 90 3940–3700 Kendrick and Pace 1985 UGa-205 Miler A (12Or12) early French Lick 4700 80 3630–3370 Munson 1980a UGa-2058 Miler A (12Or12) early French Lick 4750 85 3640–3380 Munson 1980a UGa-2062 Miler A (12Or12) early French Lick 4485 70 3340–3050 Munson 1980a UGa-2063 Omer Lane (12Or273) late French Lick? 3410 175 1940–1520 Munson 1980a UGa-2055 K Branch (12Cr27) late French Lick? 3615 65 2120–1830 Munson 1980a UGa-2056 Morganrath (12Or92) early French Lick 4725 250 3760–3100 Munson 1980a UGa-2059 Morganrath (12Or92) late French Lick 4390 85 3310–2900 Munson 1980a Beta-49082 Mogan (12Pe839) late French Lick 3920 80 2560–2290 Bader 1994 Beta-49083 Mogan (12Pe839) ? 3530 90 2010–1740 Bader 1994 Beta-6926 Bono (12Lr194) early French Lick 4920 70 3770–3650 Tomak 1982 Beta-7026 Bono (12Lr194) early French Lick 4730 70 3630–3380 Tomak 1982 UGa-4549 Schershel (12Mo152) late French Lick 4595 90 3520–3100 Tomak 1980 Beta-6347 12Sw89 early Middle Archaic 6630 100 5630–5480 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-6351 12Sw89 early French Lick 4950 60 3780–3660 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-6352 12Sw89 early Middle Archaic 6940 180 5990–5660 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-6353 12Sw89 early Middle Archaic 6560 130 5620–5380 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-6579 12Sw99 late French Lick 3610 90 2130–1780 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-6580 12Sw99 late French Lick 3860 60 2460–2210 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-6581 12Sw99 late French Lick 4040 60 2830–2470 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-6582 12Sw99 late French Lick 4090 60 2860–2500 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-6583 12Sw99 late French Lick 4220 90 2910–2640 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-6584 12Sw99 late French Lick 3690 90 2200–1950 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-6585 12Sw99 early French Lick 4760 80 3640–3380 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-6586 12Sw99 early French Lick 4740 60 3630–3380 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-3496 12Sw99 late French Lick 3260 70 1620–1450 McHugh and Michael 1984 Beta-102165 12Pe929 late French Lick 3760 50 2280–2040 Hawkins and Walley 2000 ISGS-3547 12Pe929 late French Lick 3870 70 2460–2210 Hawkins and Walley 2000 ISGS-3495 12Pe929 late French Lick 4000 70 2660–2350 Hawkins and Walley 2000 ISGS-3501 12Pe929 late French Lick 4030 70 2840–2460 Hawkins and Walley 2000 Beta-102167 12Pe929 late French Lick 4050 70 2840–2470 Hawkins and Walley 2000 ISGS-3545 12Pe929 late French Lick 4170 70 2880–2640 Hawkins and Walley 2000 ISGS-3505 12Pe929 late French Lick 4590 130 3520–3100 Hawkins and Walley 2000 Beta-102166 12Pe929 late Middle Archaic 5860 100 4840–4555 Hawkins and Walley 2000 ISGS-3552 12Pe929 late Middle Archaic 5510 120 4490–4170 Hawkins and Walley 2000 ISGS-3500 12Pe929 late Middle Archaic 5670 100 4670–4360 Hawkins and Walley 2000 ISGS-3494 12Pe929 late Middle Archaic 5860 90 4830–4600 Hawkins and Walley 2000 ISGS-2481 Paddy’s West (12Fl46) early Middle Archaic 6620 120 5660–5470 Smith and Mocas 1994 ISGS-2483 Paddy’s West (12Fl46) early Middle Archaic 6530 70 5610–5390 Smith and Mocas 1994 ISGS-2481 Paddy’s West (12Fl48) ? 3510 120 2010–1690 Smith and Mocas 1994 Beta-83547 Swan’s Landing (12Hr304) Kirk Corner Notched 9060 70 8410–8200 Mocas and Smith 1995 Beta-83548 Swan’s Landing (12Hr304) Kirk Corner Notched 9090 60 8410–8240 Mocas and Smith 1995 UGa-267 Reid (12Fl1) early French Lick 4555 70 3480–3100 Janzen 1977 UGa-309 Reid (12Fl1) early French Lick 5480 90 4450–4230 Janzen 1977 Beta-126551 Greendale (12D511) early French Lick 5100 60 3960–3800 J. Kerr, pers. comm. 2002 Beta-126522 Greendale (12D511) early French Lick 5140 60 4040–3800 J. Kerr, pers. comm. 2002 Beta-126553 Greendale (12D511) early French Lick 5100 60 3960–3800 J. Kerr, pers. comm. 2002 Beta-91281 Greendale (12D511) early French Lick 4650 80 3620–3350 J. Kerr, pers. comm. 2002 Beta? Paintown Light (12Mo193) late French Lick 3950 100 2620–2290 P. Munson, pers. comm. 2004 UGa-1129 Berry (12Gi11) early French Lick 5585 105 4540–4340 Higginbotham 1983 UGa-1130 Berry (12Gi11) early French Lick 5200 95 4220–3820 Higginbotham 1983 Archaic Period Chronology in the Hill Country of Southern Indiana 5 TTaabbllee 1100..22.. AArrcchhaaiicc RRaaddiiooccaarrbboonn AAggeess ffrroomm SSoouutthheerrnn IInnddiiaannaa., continued. Cal BC Lab No. Site Phase RCyBP S.D. 1 Sigma Reference RL-514 Berry (12Gi11) early French Lick 5150 140 4220–3770 Higginbotham 1983 UGa-1131 Berry (12Gi11) early French Lick 5370 160 4340–4000 Higginbotham 1983 DIC-2367 Breeden (12Hr11) French Lick? 4200 200 3080–2470 Bellis 1982 Beta-195820 Millersburg (12W81) early French Lick 5290 50 4220–4000 this volume Beta-195978 Millersburg (12W81) late French Lick 4120 80 2860–2580 this volume UGa-4327 Howell (12Fr157) late French Lick 4425 120 3330–2920 this volume Beta-164348 12Cl158 late French Lick 4150 40 2860–2630 White 2002 Beta-164351 12Cl158 late French Lick 4140 40 2860–2620 White 2002 DIC-1018 Oliver Vineyard (12Mo141) late French Lick 3910 60 2470–2310 Munson 1980a DIC-1019 Oliver Vineyard (12Mo141) late French Lick 3960 50 2570–2350 Munson 1980a I-1463 Riverton (11Cw170) Riverton 3320 140 1770–1430 Winters 1969 M-1284 Riverton (11Cw170) Riverton 3110 200 1600–1050 Winters 1969 M-1285 Riverton (11Cw170) Riverton 3460 250 2140–1460 Winters 1969 M-1286 Riverton (11Cw170) Riverton 3200 200 1740–1130 Winters 1969 M-1287 Riverton (11Cw170) Riverton 3270 250 1880–1220 Winters 1969 M-1289 Robeson Hill (11Lw1) Riverton 3440 200 2030–1520 Winters 1969 M-1288 Robeson Hill (11Lw1) Riverton 3490 200 2110–1530 Winters 1969 I-1462 Swan Island (11Cw319) Riverton 3450 120 1920–1620 Winters 1969 I-1461 Swan Island (11Cw319 Riverton 3450 120 1920–1620 Winters 1969 UGa-2070 Wint (12B95) Riverton 2865 215 1370–830 Anslinger 1986 UGa-2530 Wint (12B95) Riverton 3405 160 1910–1520 Anslinger 1986 UGa-3146 Wint (12B95) Riverton 2730 105 1001–800 Anslinger 1986 UGa-1902 Morton (12P80) Riverton 2760 95 1000–814 Anslinger 1986 UGa-3145 Moore Bluff Top (12Gi7) Riverton 3045 70 1410–1130 Higginbotham 1983 than 2,100 sites were reported and 922 Archaic points were encountered deposits spanning the period of 9500–10,000+ recovered in these localities under controlled survey condi- RCyBP. Occupations are contained within fine-grained tions (see Stafford 1994). alluvium underlying a low early Holocene terrace located Radiocarbon ages reported in the text are uncalibrated, along the valley margin (see Stafford 2004). Archaeological although tables show calibrated dates using Calib version deposits were discovered to a depth of more than 5 m below 4.4 (Stuiver and Reimer 1993). Ward and Wilson’s (1978) surface (bs). Case II T´ statistic was used to test the statistical coherence The basal point bar and overlying overbank units contain of clusters of dates and to establish which samples should be large hearths and light scatters of debris associated with an used to form pooled means. Calibration results and pooled Early Side Notched component. Radiocarbon ages range means are rounded to the nearest 10 years. from 10,100 ± 190 to 9680 ± 170, with one outlier at 10,370 In the remainder of the chapter, we discusses the chronol- ± 190. Four samples form a statistical cluster with a pooled ogy of each Archaic period (Early Archaic, Middle Archaic, mean of 10,060 ± 50 RCyBP (T´ = .29, χ2 = 7.81). Very .05 Late Archaic, and terminal Late Archaic), evaluating existing few diagnostics were recovered from this zone, but a good deal phases and tentatively proposing new phases or complexes on of variation exists in the points collected. Radiocarbon-dated the basis of the association of radiocarbon ages with diagnostic Feature 313, a large surface hearth, produced two points (Figure tool assemblages (see Figure 10.2). Although chronology is 10.3a, b) that fall within the enigmatic Early Side Notched the principal focus of this discussion, we also briefly sum- class. They have deep diagonal notches, squared ears, and a marize previously proposed settlement-subsistence strategies concave base. One of these hafted bifaces has been shaped into and trends in chert utilization and mortuary practices during a drill, and the blade of the other, although triangular in shape, the Archaic period. has been reworked, as evidenced by several large percussion scars. Two radiocarbon determinations were made on a split sample from the feature and have a pooled mean of 9954 ± Early Archaic (8000–10,000 RCYBP) 86 RCyBP (T´ = 3.52, χ2 = 3.84). Although similar in .05 age, the points from this feature are unlike Big Sandy I Side Notched from early southeastern contexts like Dust Cave Large-scale excavations at the James Farnsley (12Hr520) (Driskell 1996; Sherwood et al. 2004) or Stanfield-Worley site, within the CAP area, revealed a comprehensive strati- Bluff Shelter (DeJarnette et al. 1962) and are more consistent graphic record of Early Archaic components, including rarely with Thebes-cluster technology and form. 6 C. Russell Stafford and Mark Cantin ���������� ���������������� ����� ������������ ������������ ������ �������������� ���� � ���� ������� �������� �������� ���� �������� ������� ���� ���� ���������������� ���������������� ��������� ������ ���� ���� ���� ������� ����������������� ����������������� ��������������� �������� �������� ��������� ���� ���� ������������ ���� ���� ������ ������� ���� ��������������� ���� ���� ���� ��������� �������� ���� ���� ����� ���� ������� ������ ���� ������������������ ����� ������ ����������� ������������������������������������������ Figure 10.2. Archaic phases and calibrated radiocarbon age ranges for southern Indiana. Two other largely complete points were recovered from Overlying the Early Side Notched zone is a Thebes/St. this zone (Figure 10.3c, d). The stem of one has been broken Charles component. At the terrace escarpment, St. Charles and reworked (Figure 10.3c). The original haft form appears points (Figure 10.4) were recovered from small clusters of to have been side-notched, and during reworking the base of knapping debris. Only one radiocarbon date was obtained the stem was beveled. On the second point, the notching is from this zone, as little charcoal was available for recovery. An asymmetrical (Figure 10.3d), with side notching on one side AMS age of 9490 ± 60 RCyBP (Beta 153512) was obtained and corner notching on the other. The small size and overall from refuse scattered in point-bar deposits. The bar deposits blade shape are similar to the Kirk Corner Notched Small slope up to the west, where a Thebes lithic workshop is shal- variety, but such points in the Kirk zone at the top of the lowly buried (.5 m bs). Only Thebes points and drills were deposit exhibit a more invasive pressure flaking on the blade recovered from this location (Figure 10.5). No charcoal was compared with the percussion flaking on this early point. The present in the highly weathered soil in this zone. period between 9500 and 10,000 RCyBP remains difficult In the upper portion of the overbank deposits are three to define stylistically in the Midwest and Midsouth because Kirk Corner Notched occupations. Twenty-two hundred of the paucity of sites with deposits from this time frame and points were recovered along with some 10,000 lithic tools and the lack of standardized point morphologies. very high densities of lithic debitage. Other tools recovered Archaic Period Chronology in the Hill Country of Southern Indiana 7 a b 0 3 cm 0 3 cm Figure 10.4. St. Charles points from the James Farnsley site. makes up the vast majority (74 percent) of the collection, followed in frequency by Kirk Large (14 percent), Kirk Small (10 percent), and Stilwell (2 percent). Pine Tree, with its incurvate-recurvate and serrated blade has typically been viewed as a resharpened Kirk Corner Notched Large (Justice 1987; Smith 1986). At Kirk sites in the Southeast, Pine Trees c d typically make up a small percentage of point assemblages. Although resharpening is a factor in the morphology of Figure 10.3. Early Side Notched points from the James Farnsley site. Kirk-cluster points from the James Farnsley site, we argue that the Pine Tree form in this region of the lower Ohio River in association with Kirk Corner Notched points are chipped valley represents a stylistically distinctive type because of its adzes and celts, unifacial end scrapers, and distinctive long- technology, especially relative to Kirk Large. shanked, bulbous-based drills. Buried on the terrace escarp- ment is a 30-m-long secondary refuse deposit containing high densities of debitage, tools, and charcoal. Radiocarbon Kirk Point Technology and Stylistic Variability ages obtained (n = 5) from the lower Kirk zone range from 9420 ± 100 to 8780 ± 80 RCyBP. Three of the younger Cantin and Stafford (2003) have recently examined the rela- dates cluster at 8815 ± 58 RCyBP (T´ = 0.52, χ2 = 5.99). tionship between resharpening sequences and technomorpho- .05 Single ages of 8740 ± 100 RCyBP (ISGS 4838) and 8320 logical variability in the Kirk-cluster assemblage from the site. ± 80 RCyBP (ISGS 5032) were obtained from the middle As noted, the Pine Tree form dominates the assemblage from and upper occupation zones, respectively. the Kirk zone (Figure 10.6). While resharpened blades occur The very large sample of Kirk Corner Notched points whose morphology is consistent with the Pine Tree Corner recovered provides the opportunity to examine stylistic Notched type as defined elsewhere, there is also a Pine Tree variation within this cluster. We have identified four variet- style that does not represent a reworked point but, rather, is ies (Cantin and Stafford 2003): Pine Tree Corner Notched, a pristine form. Pine Tree point blades are relatively long and Kirk Corner Notched Large, Kirk Corner Notched Small, narrow and usually very well made. Of the complete blades and Stilwell Corner Notched. Pine Tree Corner Notched (n = 1,158), the typical shape in pristine forms is recurvate 8 C. Russell Stafford and Mark Cantin Perhaps the most striking attribute of Pine Tree points is the use of pressure flaking on the blade, which results in a parallel to chevron flaking pattern (Crabtree 1972). This is related to the production of a serrated blade in which the blade margin is carefully prepared to set up a platform for what Bruce Bradley refers to as “serial pressure flaking” (1997:54) or “serial serration” (pers. comm. 2003) in Dalton points. These serration flakes, regimented in their spacing, carry across the face of the blade and often terminally inter- sect to form a medial ridge. Serration is installed along the entire blade to the end of the barb. Blade serration is present in 81 percent of all Pine Trees. Of this total, serial serration is recorded for 87 percent. Serial serration is not a resharpening mechanism applied to Kirk Corner Notched Large forms. Although a subset of Kirk Large have a similar outline to Pine Tree, they lack the serial serration. Shape, then, cannot be solely used to differentiate Pine Tree from Kirk Large. Kirk Corner Notched Large points (Figure 10.7) are usually broad points, typically with excurvate blades. Flak- ing can be minimally bifacial, at times approaching unifacial. Broad, random percussion flakes dominate the face, which lacks a medial ridge. “Parallel-over-random” flaking—that is, parallel pressure flaking of the margins over a randomly percussion-flaked face—is most common, seen on 71 per- cent of points, and absolute random flaking is present on 24 percent. Pressure flaking is minimal and noninvasive on the face and is done only to shape the blade margins, not to thin the face. True Pine Tree–like parallel flaking is only observed in 3 percent of Kirk Large. Nearly half of all Kirk Large points are not serrated (48 percent), in stark contrast to Pine Trees. However, 35 percent are serrated, though the procedure used differs somewhat from that applied to Pine Tree. In Kirk Large technology, serration is accomplished by flaking only the blade margin rather than the entire blade face. While Kirk Corner Notched Small points (Figure 10.8) appear to be diminutive analogs of the Large form, in some technological aspects they are more similar to Pine Tree. The blades are most often excurvate to triangular, with stubby down-swept barbs. Over half (55 percent) have 0 3 cm parallel, narrow, deep notches, but 25 percent have broad, Figure 10.5. Thebes points from the James Farnsley site. open, shallow notches. They are routinely serrated (64 percent) and basally ground (81percent), both attributes occurring in greater frequency than in Kirk Large but in (65 percent), often with a long medial section that is parallel lesser frequency than in Pine Tree. They are often serially bladed. A prominent feature is the outswept, flaring barbs, serrated (53 percent) with a parallel flaking pattern (68 which are isolated from the blade in pristine forms and are percent), and parallel-over-random flaking is not unusual even more accentuated through blade maintenance in re- (26 percent). worked forms and can lead to a strongly incurvate blade. Of The Stilwell variety (Figure 10.9) is a large, heavy point. those with measurable notches, almost all (92 percent) have It is usually straight or recurvate bladed with an incurvate parallel, narrow, deep notches. They are almost always basally base, which is often ground (69 percent), and the blade is ground (87 percent), with grinding extending to the tips of virtually always serrated (94 percent). Flaking is most typically the barbs and within the notches. Another distinctive stylistic parallel-over-random (94 percent), reflecting serial serration feature of the Pine Tree is the exaggerated blade tip. confined to the margin. Archaic Period Chronology in the Hill Country of Southern Indiana 9 0 3 cm Figure 10.6. Pine Tree Corner Notched points from the James Farnsley site. Kirk Chronology of points is small (n = 31), Pine Tree forms are common (61 percent). Thousands more Pine Tree Corner Notched points Unlike Kirk-cluster stratigraphic sequences elsewhere, no reportedly have been recovered by collectors from the erod- strong shifts in Kirk varieties (i.e., change from Kirk Small to ing bank of the site (Smith 1986, 1995). Pine Tree points Kirk Large) are stratigraphically detectable through the more dominate the Kirk-cluster points illustrated by Tomak (1994) than meter-thick deposit at James Farnsley. Stilwell Corner from one of these collections. Radiocarbon samples from the Notched points are associated predominantly with the up- initial excavations at Swan’s Landing were much too young per occupation at the site, although Kirk Large and Small or too old by several millennia (see Smith 1986; Tankersley co-occur in this zone, as well. At the adjacent Townsend site and Munson 1992), but later excavation (Mocas and Smith (12Hr481), a Kirk cluster occupation underlies a thick Late 1995) obtained AMS radiocarbon ages of 9060 ± 70 RCyBP Archaic rock-filled midden at the terrace surface. Stilwell (Beta 83547) and 9090 ± 60 RCyBP (Beta 83548), which variety points are by far the most common Kirk form (49 are well within the range of Kirk ages elsewhere. percent), and a radiocarbon age of 8360 ± 80 RCyBP (ISGS 5025) was obtained from a pit feature. This age is consistent with that derived from the upper Kirk zone at James Farnsley. Early Archaic Summary These dates are generally outside the range of Kirk-cluster occupations in the Southeast by 700 years, so it appears likely that this stylistic form of Kirk persisted later in the lower The paucity of data associated with the late Wisconsin–early Ohio River valley. Holocene transition in the Midwest or Midsouth makes Limited excavations (Mocas and Smith 1995; Smith 1986, generalization difficult. The Early Side Notched zone at the 1995) of buried deposits at Swan’s Landing (12Hr304) on the James Farnsley site hints that lower Ohio River valley point west side of Harrison County (Figure 10.1) near the conflu- forms are stylistically different from the Big Sandy I type in ence of the Ohio River and Indian Creek have documented the Southeast and may be precursors to the Thebes tradition early Kirk Corner Notched occupations. Although the sample of the Midwest. 10 C. Russell Stafford and Mark Cantin 0 3 cm Figure 10.7. Kirk Corner Notched Large points from the James 0 3 cm Farnsley site. Figure 10.9. Stilwell Corner Notched points from the Townsend site. At the James Farnsley site, the Thebes-cluster zone is strati- graphically overlain by a series of Kirk-cluster occupations. This is a stratigraphic sequence that has not been documented elsewhere in the Midwest. The earliest Kirk-cluster age at the site is not substantially later than the single Thebes-cluster date, and we, therefore, expect that Thebes and Kirk at least partially overlapped in time. This overlap is also indicated by the Thebes-cluster dates from the Twin Ditch site in the lower Illinois River valley, which range between 9500 ± 100 and 8740 ± 70 (Morrow 1996:347). The prevalence of a technologically distinctive Pine Tree Corner Notched type at the Farnsley and Swan’s Landing sites and its relative rarity elsewhere in the Southeast suggests that a style zone may exist in this part of the lower Ohio River valley. On a narrower regional scale, Early Archaic points were the second most common Archaic diagnostic artifacts recovered (33.9 percent) in the Data Center Survey in southwestern Indiana. Kirk Corner Notched (20.6 percent) were second only to Matanzas points, while Thebes-cluster points (i.e., Thebes, St. Charles, and Lost Lake) made up 9.1 percent 0 3 cm (ranked fourth) of the Archaic points recovered. Bifurcate Figure 10.8. Kirk Corner Notched Small points from the James types ranked seventh (4.2 percent). Excavated Bifurcate sites Farnsley site. are rare in southern Indiana but include three mortuary

Description: