Archaeology: An Introduction PDF

Preview Archaeology: An Introduction

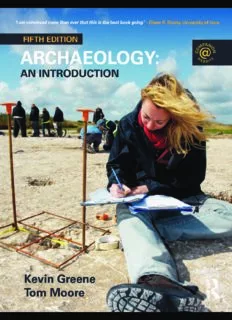

ARCHAEOLOGY AN INTRODUCTION This fully updated fifth edition of a classic classroom text is essential reading for core courses in archae- ology. It explains how the subject emerged from an amateur pursuit in the eighteenth century into a serious discipline, and explores changing trends in interpretation in recent decades. The authors convey the excitement of archaeology while helping readers to evaluate new discoveries by explaining the methods and theories that lie behind them. In addition to drawing upon examples and case studies from many regions of the world and periods of the past, the book incorporates the authors’ own fieldwork, research and teaching. Archaeology: an introduction continues to include key references and guidance to help new readers find their way through the ever-expanding range of archaeological publications. The comprehensive glossary and bibliography are complemented by a support website to assist further study and wider learning. New to the fifth edition: • inclusion of the latest survey techniques and updated material on developments in dating, DNA analysis, isotopes and population movement • coverage of new themes such as identity, personhood, and how different societies are defined from an anthropological point of view • the impact of climate change and sustainability on heritage management • increased coverage of the historical development of archaeological ideas and methods • attractively redesigned four-colour text, and colour illustrations for the first time. Kevin Greene is Reader in Archaeology at Newcastle University. Tom Moore is Lecturer in Archaeology at Durham University. What reviewers said about earlier editions: ‘A most important book. Student feedback says that that this is the ideal book – easy to read and follow at the right level, and not too complex.’ – Mick Aston, ‘A first-class book, invaluable to beginners at adult education classes and on first- year university courses.’ – British Book News ‘This book scores a bull’s eye.’ – Current Archaeology ‘An attractive introduction, useful to beginners in the field, whatever their background.’ – Antiquity ‘Kevin Greene has succeeded admirably in his task of providing an introduction to archaeology for sixth-formers, undergraduates, adult students, and the general reader with his clear exposition and skilful use of illustrations.’ – CBA Newsletter ‘A clear outline of the way archaeology has developed.’ – History Today ‘The content is sound, undogmatic and uncontroversial. As a general introduction to the subject and interpretation of the techniques of modern archaeology, it deserves to reach a wide audience.’ – Teaching History ‘A splendid book and a worthy introduction to the subject.’ – Times Educational Supplement ARCHAEOLOGY An Introduction Fifth edition Kevin Greene and Tom Moore First published 1983 Reprinted 1986, 1988 Revised edition 1990, 1991 Reprinted 1993, 1994 Revised edition 1995 Reprinted 1996, 1997 by Routledge Fourth edition 2002 This fifth edition first published 2010 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 270 Madis on Avenue, Ne w York, NY 10016 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library,2010. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. © 2002 Kevin Greene © 2010 Kevin Greene and Tom Moore Designed and typeset by Fakenham Photosetting Ltd, Fakenham, Norfolk All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book has been requested ISBN 0-203-83597-2 Mastere-bookISBN ISBN13: 978-0-415-49638-4 (hbk) ISBN13: 978-0-415-49639-1 (pbk) Contents List of illustrations ix 1.6.3 The Aegean Bronze Age: Preface xiii Schliemann and Troy 39 Acknowledgements xvi 1.6.4 Greece and the Aegean: Evans and Referencing xvii Knossos 41 1.6.5 India and Asia 41 1 THE IDEA OF THE PAST 1 1.6.6 Civilisations in the Americas 42 1.1 The intellectual history of archaeology 1 1.7 Achievements of early archaeology 43 1.1.1 Archaeology and antiquarianism, 1.7.1 Excavation: the investigative prehistory and history 5 technique of the future 44 1.1.2 The problem of origins and time 6 1.8 Guide to further reading 49 1.2 The emergence of archaeological methods 7 1.2.1 Greece and Rome 7 1.1 The past in the present: developing 1.2.2 Medieval attitudes to antiquity 8 analogies with the New World 12 1.2.3 From medieval humanism to the 1.2 William Camden (1551–1623) 14 Renaissance 10 1.3 Discovering the archaeology of 1.2.4 Archaeology and the Enlightenment 12 North America: the Mounds of 1.2.5 Antiquarian fieldwork 13 Ohio and Illinois 18 1.2.6 Antiquarianism in the Americas 17 1.4 The great societies: archaeology 1.2.7 Touring, collecting and the origin comes of age? 28 of museums 17 1.5 Plundering and collecting: Belzoni 1.2.8 Science and Romanticism 21 and Lord Elgin 38 1.3 The recognition and study of artefacts 21 1.6 Pioneer of Near Eastern 1.3.1 Scandinavia and the Three-Age archaeology: Gertrude Bell 40 System 22 1.7 V. Gordon Childe: twentieth- 1.3.2 Typology 24 century archaeology begins to 1.4 Recognising human origins 26 model the past 46 1.4.1 Evidence for human antiquity 26 1.4.2 Catastrophists, Uniformitarians, 2 DISCOVERY AND INVESTIGATION 51 and the impact of Darwin 31 2.1 Sites or landscapes? 52 1.5 From hunting to farming 32 2.2 Field archaeology 55 1.5.1 World prehistory 34 2.2.1 Field survey 56 1.6 The discovery of civilisations 34 2.2.2 Fieldwalking 57 1.6.1 Greece and Rome 35 2.2.3 Recording and topographic/ 1.6.2 Egypt and Mesopotamia 36 earthwork surveying 58 VI ARCHAEOLOGY 2.2.4 Historic landscape and monument 3.4.6 Reconstruction 135 inventories 61 3.5 Records, archives and publication 135 2.2.5 Underwater survey 62 3.5.1 Recording 135 2.3 Remote sensing 63 3.5.2 Postmodernism and excavation: 2.3.1 Airborne prospection 63 reflexive fieldwork 138 2.3.2 Geophysical and geochemical 3.5.3 Publication and archiving the results 141 surveying 72 3.6 Guide to further reading 145 2.4 Geographical information systems (GIS) 80 2.5 Landscape archaeology 82 3.1 Development of excavation 2.6 Conclusions 85 techniques: Mortimer Wheeler 90 2.7 Guide to further reading 85 3.2 Stratigraphic recording 98 3.3 Responsibilities of excavators: 2.1 Sampling in landscape survey 55 selection of items from the 2.2 Cropmark formation 64 Institute of Archaeologists’ code of 2.3 Historic Landscape conduct (October 2008) 102 Characterisation (HLC) 64 3.4 Changing research priorities: the 2.4 Airborne topographic survey: LiDAR 70 example of Roman Britain 104 2.5 Geophysical survey techniques 73 3.5 Planning and excavation: the 2.6 Geophysical survey responses 74 example of PPG16 108 2.7 GIS and predictive modelling: the 3.6 Positive features: section of Roman location of Roman villas near Veii, Ermin Street 124 Italy 81 3.7 Negative features: Iron Age storage pits 125 3.8 Surfaces: floor levels 126 3 EXCAVATION 89 3.1 The development of excavation techniques 89 4 DATING THE PAST 148 3.1.1 The concept of stratification 90 4.1 Background 148 3.1.2 General Pitt Rivers 92 4.2 Typology and cross-dating 149 3.1.3 Developments in the twentieth 4.2.1 Sequence dating and seriation 153 century 93 4.3 Historical dating 155 3.1.4 Mortimer Wheeler 93 4.3.1 Applying historical dates to sites 157 3.1.5 From keyhole trenches to open 4.4 Scientific dating techniques 160 area excavation 95 4.4.1 Geological time-scales 160 3.1.6 The future of excavation 97 4.4.2 Climatostratigraphy 161 3.2 The interpretation of stratification 100 4.4.3 Varves 162 3.2.1 Dating stratification 100 4.4.4 Palynostratigraphy 163 3.3 Planning an excavation 101 4.4.5 Dendrochronology 164 3.3.1 Excavation, ethics and theory 101 4.5 Absolute techniques 167 3.3.2 Selection of a site 102 4.5.1 Radioactive decay 167 3.3.3 Developer-funded archaeology 107 4.5.2 Radiocarbon dating 167 3.3.4 Background research 109 4.5.3 Presenting and interpreting a 3.4 Excavation strategy 111 radiocarbon date 171 3.4.1 Forms of sites 112 4.5.4 The Bayesian radiocarbon 3.4.2 Excavation in special conditions 118 revolution 175 3.4.3 Contexts and features 122 4.5.5 Potassium–argon (40K/40Ar) and 3.4.4 Structures and materials 127 argon–argon dating (40Ar/39Ar) 176 3.4.5 Standing buildings 133 4.5.6 Uranium series dating 177 CONTENTS VII 4.5.7 Fission-track dating 177 5.6.5 Genetics and DNA 223 4.5.8 Tephrochronology 178 5.7 Artefacts and raw materials 227 4.5.9 Luminescence dating 178 5.7.1 Methods of examination and 4.5.10 Electron spin resonance (ESR) 182 analysis 228 4.6 Derivative techniques 183 5.7.2 Stone 231 4.6.1 Protein and amino acid diagenesis 5.7.3 Ceramics 233 dating 183 5.7.4 Metals 235 4.6.2 Obsidian hydration dating 184 5.8 Conservation 237 4.6.3 Archaeomagnetic dating 184 5.8.1 Ancient objects 237 4.7 The authenticity of artefacts 186 5.8.2 Historic buildings and 4.8 Conclusions 187 archaeological sites 238 4.9 Guide to further reading 189 5.9 Statistics 239 5.10 Experimental archaeology 240 5.10.1 Artefacts 242 4.1 Using seriation: Native American 5.10.2 Sites and structures 242 sites in New York State 156 5.11 Conclusion 244 4.2 Which dating technique? 159 5.12 Guide to further reading 244 4.3 Alchester: dendrochronology in action 165 4.4 The first radiocarbon revolution: 5.1 Climate and the human past 194 Willard Libby 169 5.2 Small but vital: plant and animal 4.5 Vikings, fire and ice: the remains recovered by means of application of tephrochronology 179 flotation 199 4.6 Optical stimulated luminescence: 5.3 Domestication of maize in the Deaf Adder Gorge, Australia and Americas 203 Wat’s Dyke, Wales 182 5.4 Charting animal domestication 209 4.7 Dating an archaeological excavation 188 5.5 Ceramics and food remains: gas chromatography 212 5.6 Human remains and evidence of 5 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SCIENCE 190 warfare: Towton Moor 218 5.1 The nature of science 191 5.7 DNA and disease: the archaeology 5.2 The environment 192 of tuberculosis 218 5.3 Climate 193 5.8 Movement and migration: Bronze 5.4 The geosphere 196 Age Beaker burials 220 5.4.1 Geology 196 5.9 Isola Sacra: diet and migration in 5.4.2 Soils 196 Ancient Rome 222 5.5 The biosphere 198 5.10 Roman coins 238 5.5.1 Plants 198 5.11 Experimental archaeology: glass in 5.5.2 Animals 205 Egypt 241 5.5.3 Fish 210 5.5.4 Shells: archaeomalacology 212 6 MAKING SENSE OF THE PAST 249 5.5.5 Insects and other invertebrates 214 6.1 Where is archaeology at the beginning 5.6 Humans 214 of the twenty-first century? 249 5.6.1 Burials 216 6.1.1 Too much knowledge? 250 5.6.2 Palaeopathology and evidence 6.2 Archaeological theory 252 from human remains 217 6.2.1 Social evolution 256 5.6.3 Diet 219 6.2.2 Culture history 258 5.6.4 Movement and migration 221 6.3 Towards processual archaeology 263 VIII CONTENTS 6.3.1 The New Archaeology 264 6.3.2 Ethnoarchaeology and Middle 6.1 Archaeological theory and Range Theory 269 changing perspectives 251 6.4 Towards postprocessual archaeology 273 6.2 Are all visions of the past equal? 6.4.1 Postprocessualism 273 Pseudo-archaeology 253 6.4.2 Reflexive thinking 274 6.3 Nationalism and archaeology 261 6.4.3 Modernity, modernism and 6.4 Reconstructing past societies: postmodernism 274 hierarchies, heterarchies and social 6.5 Interpretive archaeology 282 complexity 267 6.5.1 Agency, structuration and habitus 283 6.5 Phenomenology: 6.5.2 Archaeologies of identity 285 postprocessualism and landscape 6.5.3 Gender 288 archaeology 277 6.5.4 Artefacts: biographies, materiality, 6.6 Heritage management: state fragmentation and personhood 290 protection 297 6.5.5 Conflict, compromise or pluralism? 292 6.7 Tourism and heritage: Kenilworth 6.6 Archaeology and the public 294 Castle 298 6.6.1 Heritage management: controlling 6.8 Managing our heritage in the the present by means of the past? 294 21st century: climate change and 6.6.2 Archaeology and the State 295 archaeology 300 6.6.3 Museums: from Art Gallery to 6.9 Lost treasures of Iraq: war and ‘Experience’ 299 cultural heritage 307 6.6.4 Heritage management and heritage 6.10 Archaeology and ethics: the case of practice: the case of Stonehenge 302 human remains 308 6.6.5 The antiquities trade 304 6.6.6 Archaeology in the media 306 6.7 Conclusion 307 6.8 Guide to further reading 310 Glossary 313 Bibliography 322 Index 380 List of illustrations Frontispiece Time line and major developments BOX 1.1 Drawing of North American Indian by in the human past John White BOX 1.2 Engraving of William Camden BOX 1.3 A Cahokia mound, Illinois Chapter 1 BOX 1.4 Cartoon of Society of Antiquaries by 1.1 Poster for One Million Years bc George Cruikshank, 1812 1.2 Behind the arch of Hadrian, Athens BOX 1.5 The new Parthenon museum, Athens 1.3 Emperor Hadrian BOX 1.6 Gertrude Bell at Duris, Lebanon 1.4 Stonehenge drawing in 15th-century BOX 1.7 V. Gordon Childe manuscript 1.5 William Stukeley at Avebury Chapter 2 1.6 Ole Worm’s collection 1.7 Lord Fortrose’s apartment in Naples, 1770 2.1 Fieldwalking on the Milfield project 1.8 Stone implements from Britain and the 2.2 Shovel testing at Shapwick New World 2.3 GPS survey, Spain, and Total Station survey, 1.9 C.J. Thomsen in the Oldnordisk Museum, Gloucestershire Copenhagen 2.4 Hachured plan of Chew Green earthworks 1.10 The typology of Bronze Age axes 2.5 Aberdeenshire SMR/HER entry page 1.11 Reginald Southey with human and ape 2.6 Aerial photograph of Roman forts at Chew skeleton and skulls Green 1.12 Memorial to John Frere 2.7 Aerial photograph of cropmarks at 1.13 Jacques Boucher de Perthes Standlake, Oxfordshire 1.14 Section drawing by Boucher de Perthes 2.8 Aerial photograph of snow site at Yarnbury 1.15 Prestwich axe Castle, Wiltshire 1.16 Map of domestication and civilisations 2.9 Plot of geophysics prospecting results 1.17 Engraving of the Parthenon, Athens 2.10 GPR in action in Sweden 1.18 Schliemann’s excavations at Troy 2.11 Cumbrian landscape at Wasdale Head 1.19 View of Monjas, Chichén Itzá, Mexico 1.20 Plan of Chichén Itzá, Mexico BOX 2.1 Sampling in landscape survey 1.21 Carving from Copán, Honduras BOX 2.2 Cropmark formation 1.22 Excavations at Babylon BOX 2.3 Historic Landscape Characterisation 1.23 Section drawing, Babylon (HLC) 1.24 Blaenavon ironworks BOX 2.4 Airborne topographic survey: LiDAR BOX 2.5 Geophysical survey techniques

Description: