aqa econ3 answers 25 mark questions june 2012 PDF

Preview aqa econ3 answers 25 mark questions june 2012

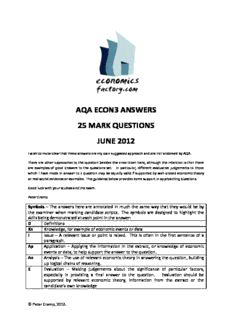

AQA ECON3 ANSWERS 25 MARK QUESTIONS JUNE 2012 I wish to make clear that these answers are my own suggested approach and are not endorsed by AQA. There are other approaches to the question besides the ones taken here, although the intention is that these are examples of good answers to the questions set. In particular, different evaluative judgements to those which I have made in answer to a question may be equally valid if supported by well-placed economic theory or real world evidence or examples. The guidance below provides some support in approaching questions. Good luck with your studies and the exam. Peter Cramp Symbols – The answers here are annotated in much the same way that they would be by the examiner when marking candidate scripts. The symbols are designed to highlight the skills being demonstrated at each point in the answer: D Definitions Kn Knowledge, for example of economic events or data I Issue – A relevant issue or point is raised. This is often in the first sentence of a paragraph. Ap Application – Applying the information in the extract, or knowledge of economic events or data, to help support the answer to the question. An Analysis – The use of relevant economic theory in answering the question, building up logical chains of reasoning. E Evaluation – Making judgements about the significance of particular factors, especially in providing a final answer to the question. Evaluation should be supported by relevant economic theory, information from the extract or the candidate’s own knowledge © Peter Cramp, 2012. GUIDANCE 1. It is common exam practice to define key terms in the question in the introduction to your essay. 2. The first sentence of each main paragraph of your work should clearly specify the point or issue which will be analysed in the paragraph. 3. The issue to be analysed in each paragraph should be clearly related to the question. Suppose the question is “Evaluate ways in which governments can make markets more competitive.” It is appropriate to use paragraphs beginning “One way in which governments can make markets more competitive is………” 4. The analysis in each paragraph should be a logical chain of reasoning. The more detailed this analysis is, the better, so include as many “links” in your chain as possible. 5. Appropriate use of economic diagrams is another way of demonstrating the skill of analysis 6. You must have tight focus on the question set. Good economic analysis, but based on material which is irrelevant or of borderline relevance may result in a lower mark than if the material had not been included. 7. The skill of evaluation is vital to scoring high marks for 25 marks answers. This involves making reasoned judgements in response to the question. 8. The main place that evaluation is expected in your work is in your conclusion. You must reach a final judgement that answers the question set and your judgement must be backed substantially by appropriate economic theory and/or “real world evidence” 9. You are also likely to include some evaluation in the main body of your essay. This can usefully be undertaken at the end of a paragraph following substantial analysis, or in a separate evaluative paragraph following on immediately. 10. The more specific your judgement can be the better. Suppose for instance that the question is “Evaluate the view that the government should not regulate prices in utility industries such as gas, electricity and water”. A candidate might argue that the government does not need to regulate prices if there is sufficient competition in the market to ensure that prices are kept low. This is indeed an example of evaluation. It would be stronger evaluation if the point were supported by an assessment of how competitive utility markets are in reality. Suppose a second candidate were to take the same starting point, but went on to argue that the water industry is not competitive, and this is associated with the fact that it is a natural monopoly. Further, in gas and electricity markets, there are several firms for customers to choose from, but there has been some evidence that demand for the services of any one firm is inelastic, due to consumer inertia or lack of knowledge. This has allowed firms to raise prices to customers more than any increases in their © Peter Cramp, 2012. costs of production. If the second candidate cited this evidence and concluded that it provides a basis for the government to regulate prices, he or she would have undertaken much stronger evaluation than the first candidate. This is because a specific and supported judgement has been made about how appropriate regulation of prices would be in the utility industries stated in the question. It is a good idea to study previous questions and to have a stock of examples and real world data that would help to answer them. You can pick up such examples from these suggested answers. © Peter Cramp, 2012. AQA ECON3 JUNE 2012 CONTEXT 1 D Economically, pollution and climate change are regarded as negative externalities. They are third party effects of economic activity, and are received outside of the market in the sense that those who suffer are not paid compensation. An In the absence of government intervention, firms and consumers are able to pollute the environment free of charge, with market price failing to reflect the full social cost of production and goods associated with pollution being over-provided. This constitutes a market failure, and is illustrated in the diagram. An Diagram Market prices fail to reflect the full social cost of production. I/E This analysis immediately suggests that the main impact of policies to reduce pollution and climate change for UK firms is negative. An This is because correcting the market failure will involve accounting for the external cost of production, and thus adding to the production costs of firms. Unless they are able to pass on all of the increase in costs to consumers, firms will suffer from reduced profit margins on each unit of the good they supply. Even if they do raise the price in order to maintain profit margins, there is likely to © Peter Cramp, 2012. be a contraction in demand and a reduced quantity sold. For this reason, policies to protect the environment are often seen to be against the interests of businesses. I One policy to prevent pollution and climate change is regulation of emissions in the form of quotas, which place a legal limit on the amount of pollution firms are allowed to undertake. An/E The effect of such regulations may differ widely from firm to firm. Some firms might find the quota allocated to them exceeds the amount of pollution they are currently producing and would therefore not be affected at all or may gain from the damage done to their competitors. Other firms may find it very expensive to comply with regulations, for example because they are currently using relatively old capital in their production process. Such firms may be placed at a severe cost disadvantage by the regulations and would face closure if they were unable to compete as a result. I/Ap It is unsurprising that “some UK businesses prefer permit trading to alternative policies”. An These allow firms who are unable to control pollution easily to purchase spare permits from other firms. Assuming rational behaviour, trades of permits will only take place if they are beneficial to both firms. The purchasing firm is spared the expense of costly measures to control emissions, while the selling firm gains revenue from the permits they do not need. While firms who resort to purchasing permits would surely prefer to be allowed to carry on polluting the environment free of charge, this solution is less damaging to them than one of regulation. I/E In many ways, this policy appears the most sensible because it rewards firms for further reducing their pollution. An Greener firms who would be unaffected by a quota could achieve financial gain by further reducing their pollution to generate more spare permits to sell within a permit trading system. I/E A policy of taxing fuel would raise production costs of firms, but this would affect those firms who use a great deal of fuel disproportionately. An/E This would apply particularly to manufacturers, as fuel is needed in both the production process and for the transportation of goods. On the other hand, service industries might have little to fear from a tax on fuel, especially those whose services are provided electronically. This argument could also be applied to other policies such as carbon trading. Such policies could be a “further blow to UK manufacturing” with “service industries……..treated more leniently”. I There is a potential for policies aimed at reducing pollution to benefit any UK firms specialising in green technologies. An Firms needing to comply with environmental policies are more likely to invest in capital incorporating such technologies. Not only would this generate revenue for firms selling such capital, it would also create the potential for them to exploit economies of scale through access to a larger market, thus reducing costs of production. E This said, much of any new capital purchased by UK firms may actually be sourced from elsewhere in the world rather than from UK businesses. © Peter Cramp, 2012. Evaluation/final judgement (s) An While there are winners amongst UK firms from policies to tackle pollution and climate change it is the case, then, that UK firms are likely to suffer in general as a result of the effect that compliance with such policies will raise their costs of production. Permit trading has the potential to minimise this damage by allowing firms to purchase spare permits from other firms when this allows a cost saving compared to limiting their pollution. I A further important issue when assessing how much damage might be done to UK firms by policies to reduce pollution is the extent to which firms in other countries are subject to similar policies. Ap As noted in the extract “China, like the USA, did not sign up to the Kyoto protocol”. An If environmental policies are put in place by the UK government in isolation, this would put our firms at a cost disadvantage. Not only would this limit the effectiveness of the environmental policy in meeting its aims (Ap “it can be argued that factories located in China are actually producing UK emissions”), this would also be severely damaging to UK businesses. At the very least, UK firms would need environmental policies to be applied across the EU, where they do so much of their trade, if they were not to suffer greatly. I It could possibly be argued that environmental regulations benefit UK firms in the long term by increasing the sustainability of production, but even this argument carries less weight if firms elsewhere in the world are allowed to continue to pollute and is unlikely to impress firms who have to deal with increased production costs as a result of environmental protection. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that environmental policies, even if they are successful in their aims, are damaging to the short and medium term interests in UK firms. © Peter Cramp, 2012. AQA ECON3 JUNE 2012 CONTEXT 2 D/Kn Income is a flow derived from a stock of assets. The majority of income is earned by labour in the form of wages and can be seen as a return to human capital. The distribution of income tends to be very unequal when determined by market forces. An This can be seen as efficient. For example, a high wage can act as an incentive to attract highly skilled workers into those sectors of the economy where they are most productive. I Very unequal distributions of income are widely thought to be unfair, however, and treated as a market failure regarding government intervention. Ap This viewpoint has gained support in recent years as the gaps between high and low paid earners have widened, to the extent that by 2005 the top 1% of earners received close to 18% of all income in the UK economy (Extract D). Ap The extract also notes that “fairness is difficult to define”. An This recognises the fact that the concept is normative in nature, although there is growing acceptance that it would be desirable for the distribution of income to be more equal. I One element of redistributing income after it has been earned is progressive taxation. An In a progressive system the average rate of tax increases with income. Kn The current top rate of tax in the UK is 45p in each pound earned, compared to a basic rate of 20p. An The higher marginal rate for top earners pulls up their average rate, reducing post-tax income. Thus the distribution of income can be made more equal by making the tax system more progressive. This would involve increasing tax rates for high income earners compared to their current levels, or reducing tax rates for low income earners. Kn A recent example has been the substantial increase in the tax free allowance, lifting some low-paid workers out of paying taxes altogether. An/E This has the added supply-side benefit of improving incentives to work amongst low-paid workers, by increasing their take-home pay relative to the alternative of benefit payments. I Redistribution after income has been earned also requires the payment of benefits. An These can be either universal (available to everyone, regardless of income) or means-tested (only available to those whose incomes are sufficiently low to qualify). Even universal benefits reduce inequality, as they account for a higher proportion of the disposable income © Peter Cramp, 2012. of the low paid than the higher paid. Means-tested benefits are better targeted on those who need support and do more to reduce inequality. I Both progressive taxation and means-tested benefits can be seen as disincentives to work and this effect can be especially serious when the two interact, combining to make a poverty trap. An As additional income is earned, means-tested benefits may be withdrawn, while progressive taxation will lead to a higher proportion of income being paid in tax. Taken together, this can leave a low paid or unemployed worker little better off by accepting opportunities to earn additional income. In extreme cases, the effective marginal rate of taxation might be close to or in excess of 100% removing the financial incentive to earn additional income altogether. Hypothetically, if earning an additional £100 of income resulted in the loss of £90 of benefits and the payment of £20 in income tax, for example, the effective marginal tax rate would be 110%. An/E The poverty trap is generally regarded as being the most serious criticism of attempts to redistribute income. This is because it hinders the low paid in attempts to escape poverty and, creates a reliance on the taxpayer, which is damaging to government finances. Still further, by limiting the supply of labour it acts as a constraint on the capacity of the UK economy. I The existence of national minimum wages is also an attempt to make the distribution of income more equal. An This acts as a pay floor, making it illegal to employ workers at below the set wage. An/E While this has the potential to narrow pay gaps, it also has the potential to backfire by raising the wage above the revenue productivity of some workers. Profit maximising firms would respond to this situation by making some workers redundant, leading to unemployment. This is not helpful in terms of the objective of the policy. If labour demand is particularly elastic as it may be for some groups of workers such as the young, this policy has the potential to be damaging. As suggested by the extract, the lack of a European wide minimum wage may exacerbate such effects as firms choose to locate where they can enjoy lower wage costs and therefore competitive advantages. Evaluation/final judgement (s) Against this background, it is difficult to argue with the claim that it is desirable to tackle inequality of income from the supply-side, through the workings of a competitive labour market. An If systems of education and training can be improved, this raises the human capital and hence the productivity of those supplying their labour. There is a higher demand for workers with higher levels of productivity, enabling them to command a higher wage, as shown in the following diagram. © Peter Cramp, 2012. An Diagram The effect of improved education and training on wages An The advantages of such a solution are many. Not only are the workers less likely to be reliant on state support, the availability of skilled labour increases the competitiveness of UK firms and the competitiveness of the UK economy, which would become a more attractive location for multi-national corporations, leading to greater foreign direct investment into the UK. The capacity of the UK economy and its macroeconomic performance would be expected to improve. Kn While this is desirable, however, it is not necessarily easy to achieve. Successive governments have made improving the UK’s education system a top priority, and have both increased its funding and changed its workings in order to achieve improvements. In spite of this, the UK has struggled to close its productivity gap against key comparator nations such as Germany and the USA, and the gap between high and low income earners has increased remorselessly. An Even if inequality could be significantly reduced from the supply-side, there always needs to be a safety net to support the working poor and unemployed, given that the alternative of leaving some in absolute poverty is unacceptable. Unfortunately, it is very difficult to design a tax and benefits system that removes “poverty trap” effects altogether. Again, successive governments have tried to “make work pay” with only limited success and in the process have arguably made the tax and benefits system more complex than it once was. An In terms of economic theory, then, the damaging effects of incentives to work and the danger of poverty traps means that it is less desirable to redistribute income after it has been earned than it is to achieve fairness by removing supply-side obstacles. In practice, however, the immediate need to provide support for the less well off in society means that redistribution of income will continue to be important, in the face of the difficulties associated with it. © Peter Cramp, 2012. AQA ECON3 JUNE 2012 ESSAY 1 D/Kn The size of a firm is most commonly measured in terms of the number of its employees. For example, the European Commission defines a firm micro firm as having fewer than 10 employees, with the thresholds being 50 and 250 employees for small and medium sized companies respectively. However, the size of a firm can also be measured in other ways such as the turnover of the company, the value of the capital that it employs, or its market share. Economic efficiency covers the relationship between scarce factors of production and the outputs produced. I One reason for supposing that large firms might be more efficient than small firms is the existence of economies of scale. An Firms are considered to be productively efficient if they achieve the lowest possible unit cost (average cost of production) and this implies reaping any cost savings that are available to firms through being large. They may arise, for instance, through employing specialist managers, through cheaper loans due to the extra security provided by large size or through the bulk buying of inputs to the production process. D The minimum efficient scale of production describes the level of output that a firm must achieve in order to benefit from all available economies of scale. I It is not necessarily true that firms have to be large in order to reach this scale, however. An/E In some industries, often services, the minimum efficient scale may be only a small percentage of the output of the industry as a whole. On the other hand, in more capital intensive areas of the economy, there is greater potential for spreading fixed costs over a greater amount of output. Here, achieving large size becomes more important to efficient production. Indeed, some industries with large scale infrastructure but relatively small variable costs are considered to be natural monopolies where any duplication by breaking the industry into smaller companies would raise average costs and be economically wasteful. Kn The water industry is a likely example, and could be represented by a continually falling average cost curve. I It is also possible that large firms may experience diseconomies of scale. An Production costs may rise, for example, as firms become too large to manage efficiently and the costs of maintaining flows of information within the company increase. E It is difficult to judge the © Peter Cramp, 2012.

Description: