Ancient Egyptian magic PDF

Preview Ancient Egyptian magic

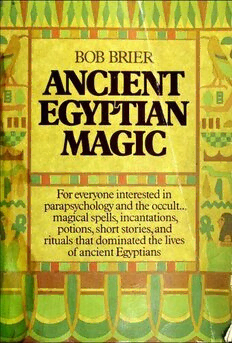

BOB BRIER For everyone interested in parapsychology and the occult .... magical spells, incantations, potions, short stories, and rituals that dominated the lives of ancient Egyptians 7;:s '/ A11cie11t &g11ptia11 Magic co MEDITERRANEAN SEA Sidon .Damascus .J Jerusalem ·a ARABIA ltP E 65 B.C.) AFRICA Syene Is t Carorac 1nd Cata,oct Co1aracr THE EGYPTIAN EMPIRE HobHrier L New York 1981 Copyright © 1980 by Bob Brier Grateful acknowledgment is made for perm1ss10n to reprint Chapter 17 from Ancient Egyptian Literature by William K. Simpson, Yale University Press, New Haven, copyright © 1972 by Yale University, with permission of Yale University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Inquiries should be addressed to William Morrow and Company, Inc., 105 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Brier, Bob. Ancient Egyptian magic. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Magic, Egyptian. I. Title. [BF1591. B75 1981] 133.4'3'0932 81-11224 ISBN 0-688-03654-6 AACR2 ISBN 0-688-00796-1 (pbk.) Printed in the United States of America 7 8 9 10 BOOK DESIGN BY BERNARD SCI-ILEIFER eo11te11ts Acknowledgments 8 Introduction 10 1. Egypt 13 2. Hieroglyphs 22 3. Magicians 34 4. Medicine 55 5. Mummification 67 6. The Pyramids 96 7. The C'offin Texts 119 8. The Book of the Dead 130 9. Amulets 141 10. Magical Servant Statues 169 11. Magical Objects in Tutankhamen's Tomb 181 12. Letters to the Dead 200 13. Oracles 205 14. Dreams 214 15. An Egyptian Horoscope Calendar 225 16. Greco-Roman and Coptic Magic 253 17. Tales of Magic 266 18. Spells for All Occasions 282 Notes 297 Selected Bibliography 304 General Index 313 Name Index 318 Egyptian Word Index 322 Acknowledgments people on three continents who have helped me THERE ARE MANY to prepare this book. In Africa there are n1y Egyptian friends and colleagues who helped me gain access to the 1naterials and informa tion I needed. I should like to thank ~1s. Chah Mafouz for being so ,villing to take 111e to her numerous friends ,vho had the keys to the locked tombs. At the Cairo Museum there is Dr. Dia Abu el Ghazi who so often worked her magic to get things done quickly. I should also like to thank Dr. Ga1nal Mokhtar, the former president of the E ryptian Antiquities Service, for his kind invitation to con1e to 6 Egypt to do 1ny research. In Luxor there are Naguib and Mustafa with whon1 I spent n1any pleasant hours drinking tea in front of Hassani's shop, talking about Egyptology and always benefitting fro1n their knowledge. In Europe there is Dr. T.G.H. Jan1es of the British Museu1n, who was so helpful in obtaining photos of the 1nuseu1n 's collection. On this continent there are almost too many to name. The C. W. Post College Research Committee assisted in the preparation of the n1anuscript with a generous grant. Dr. Virginia Lee Davis read several chapters and 1nade important suggestions. Russell Rudz wick was always willing to photograph magical objects at any time of the night. At the Brooklyn Museum Drs. Bernard Bothn1er and Robert Bianchi were extremely helpful in obtaining photos as was Dr. Christine Liliquist at the Metropolitan Museu1n of Art. Judith Turner did the line drawings for the Amulets chapter. A special thanks must go to 1ny colleague Hoyt Hobbs who put aside the writing of his own book on Egypt to help 1ne ready this book for 8 9 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS publication. I cannot praise highly enough the advice of my editor, Eunice Riedel. She was always willing to deal with problems rang ing from the organization of the manuscript to the intricacies of transliterating hieroglyphs into English. She has contributed a great deal to whatever intelligibility this book has. Thanks are also due to Carol Conklin, who helped with the translation of the Brooklyn Magical Papyrus; Diane Guzn1an, the librarian of the Brooklyn Museu1n's Wilbour collections; and Mary Chipman for her help in restoration of the menyet-necklace shown on page 161. Finally, I should like to thank my second editor, n1y wife Bar bara. She put aside her own writing projects to edit the very rough copy which I produced, often typed late at night, and was ready the next morning to discuss the 1nanuscript. More in1portant than her help on the manuscript, she was able to tolerate its author. J11troductio11 "magic" in our vocabularies, it is a c:Ufficult \VHILE WE ALL USE \vord to define. In the 1920s Lvnn Thorndike, the Colu,nbia Uni- , versity scholar, began publishing his 1nonun1ental eight volumes on the History of 1"1 agic and Experimental Science. Despite the wealth of inforn1ation, nowhere in the eight volu1nes is there a clear defini tion of " ,nagic." There are two reasons the word is so difficult to define. First, ",nagic" has had nu,nerous ,neanings over the last four thousand years. Second, religion, n1agic's sister discipline, is in 1nany ways indistinguishable fro111 it. In our con1n1on speech, "n1agic" i1nplies falsity, or trickery. A 1nagician is one who uses deceit. This association of 1nagic with falsity is a relatively new develop1nent. The word derives fro1n niagi, the Greek word for the wise 1nen of Persia and Babylonia. TI1ese men were considered powerful, but their powers were for eign to the Greeks. The concept of 1nagic as foreign, then, was at first essential to the definition of the word, and to this day there is a holdover of this belief. Whenever occult or supernatural powers are discussed, people are 1nore willing to believe in the1n if they are attributed to a swan1i iu India or a holy ,nan in Tibet than if the clai1n is for a neighbor in the Bronx. Eventually, this notion of 1nagic: as son1ething efficacious but foreign changed to so1nething still efficacious but essentially evil. Finally, there evolved the n1od ern view of 1nagic as in1potent foolishness. Ntagic is often difficult to delineate fro1n religion because both involve belief in the supernatural and deal with the realn1 of the unseen. Undeniably, the ancient Egyptians had both religious and 1nagical practices, and so1netiines it is altnost iinpossible to decide 10