An Entertainment for Angels PDF

Preview An Entertainment for Angels

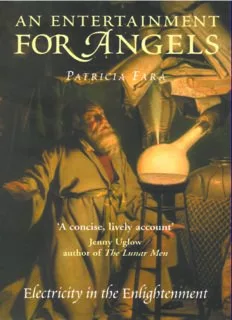

AN ENTERTAINMENT FOR ANGELS PATRICIA FARA 'A concise, lively account' Jenny Uglow author of The Lunar Men Electricity in the Enlightenment REVOLUTIONS IN SCIENCE An Entertainment for Angels Electricity in the Enlightenment Patricia Fara Series editor: Jon Turney ICON BOOKS UK TOTEM BOOKS USA Published in the UK in 2002 Published in the USA in 2002 by Icon Books Ltd., Grange Road, by Totem Books Duxford, Cambridge CB2 4QF Inquiries to: Icon Books Ltd., E-mail: [email protected] Grange Road, Duxford, www.iconbooks.co.uk Cambridge CB2 4QF, UK Sold in the UK, Europe, South Africa Distributed to the trade in the USA and Asia by Faber and Faber Ltd., by National Book Network Inc., 3 Queen Square, London WC1N 3AU 4720 Boston Way, Lanham, or their agents Maryland 20706 Distributed in the UK, Europe, Distributed in Canada by South Africa and Asia by Penguin Books Canada, Macmillan Distribution Ltd., 10 Alcorn Avenue, Suite 300, Houndmills, Basingstoke RG21 6XS Toronto, Ontario M4V 3B2 Published in Australia in 2002 ISBN 1 84046 348 1 by Allen & Unwin Pty. Ltd., PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065 Text copyright © 2002 Patricia Fara The author has asserted her moral rights. Series editor: Jon Turney Originating editor: Simon Flynn No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Typesetting by Hands Fotoset Printed and bound in the UK by Mackays of Chatham plc Contents List of Illustrations iv Introduction 1 Part I Illuminations: The Light of Reason 5 Chapter 1: Interpretations 9 Chapter 2: Electricity and Enlightenment 12 Part II Shocking Inventions: Instruments 25 Chapter 1: Robert Boyle and the Air-pump 30 Chapter 2: Francis Hauksbee and the Electrical Machine 38 Chapter 3: Stephen Gray and the Charity Boy 42 Chapter 4: Pieter van Musschenbroek and the Leyden Jar 51 Part III Lightning Cures: Applications 63 Chapter 1: Benjamin Franklin 67 Chapter 2: Knobs or Points? 76 Chapter 3: The Business of Medicine 82 Chapter 4: Therapeutic Shocks 91 Part IV Sparks of Imagination: Theories 99 Chapter 1: Problems 103 Chapter 2: Fluids and Atmospheres 111 Chapter 3: Theological Aethers 116 Chapter 4: Measurement and Mathematics 123 Part V The Flow of Life: Current Electricity 133 Chapter 1: Henry Cavendish and the Torpedo 137 Chapter 2: Luigi Galvani and his Frogs 145 Chapter 3: Alessandro Volta and his Pile 153 Chapter 4: Resuscitation 165 Further Reading 171 Notes 173 Other titles available from Icon / Totem 178 List of Illustrations 1 Benjamin Franklin 6 2 A New Electrical Machine for the Table 14 3 Robert Boyle’s first air-pump 31 4 Wright of Derby, ‘The Alchymist’ 35 5 The hanging boy 45 6 Benjamin Rackstrow’s beatification 48 7 The Leyden experiment, and the flow of electrical matter 53 8 Adam Walker’s electrical experiments 59 9 Benjamin Wilson’s experiment at the Pantheon in 1777 80 10 ‘The Quacks’: James Graham and Gustavus Katterfelto 86 11 Monitoring electric therapy with Timothy Lane’s electrometer 89 12 Charles Coulomb’s torsion balance 126 13 Henry Cavendish’s artificial torpedo 142 14 Luigi Galvani’s frogs 149 15 Alessandro Volta’s pile 157 Dedication For Helen and Katherine Acknowledgements I should like to thank Simon Flynn and Jon Turney for their very helpful editorial suggestions. I am also extremely grateful to Jim Secord and Simon Schaffer, who have made it possible for me to write this book. Picture Acknowledgements The illustrations on pages 14, 31, 45, 48, 53, 59, 80, 89, 126, 142, 149 and 157 are reproduced by permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library. Introduction What gave my Book the more sudden and general Celebrity, was the Success of one of its propos’d Experiments ... for drawing Lightning from the Clouds. This engag’d the public Attention every where. Benjamin Franklin, Autobiography, 1788 The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley was fascinated by scientific experiments. One of his friends described how he would pull out an electrical machine from the clutter on his desk, and charge himself up ‘so that the fierce, crackling sparks flew forth; and ... his long, wild locks bristled and stood on end’. His eyes gleaming with enthusiasm, Shelley prophesied that science would find a way to keep poor people warm during the coldest winters. ‘What a mighty instrument would electricity be’, enthused Shelley, as he envisaged a future when ‘by means of electrical kites we may draw down the lightning from heaven! ... an immense volume of electricity, the whole ammunition of a mighty thunderstorm; and this 1 being directed to some point would there produce the most stupendous results.’1 Drawing‘Lightning from the Clouds’: this vision- ary dream had been converted into reality by an American printer, Benjamin Franklin. Like Shelley, Franklin valued electricity for its potential benefits as well as its exciting effects. He was one of the eighteenth century’s leading diplomats, internation- ally acclaimed for his enlightened attitude and democratic ideals. Yet he was also a prominent electrical researcher, famous for his numerous inventions and groundbreaking theories that had helped to establish the new science of electricity. Although he did not embark on his electrical career until he was forty, Franklin’s scientific eminence paralleled his political reputation. Electricity was the greatest scientific invention of the Enlightenment. Shelley was showing off his skills in 1810, but only a hundred years earlier, electrical science had not existed. Virtually the only way to produce electricity was by rubbing amber or a compliant cat, and even experts knew little that had not been familiar to the Greeks. Yet by the middle of the eighteenth century, electrical experiments were being performed all over Europe with new, powerful instruments that could produce, store and discharge static electricity. 2 Far from being an arcane preoccupation reserved for privileged intellectuals, electricity rapidly became a topic of conversation throughout society. Super- latives abounded: electricity was ‘replete with wonders’, ‘as surprising as a miracle!’, ‘favourite object and pursuit of the age’. It was, one admirer exclaimed,‘an Entertainment for Angels, rather than for Men’.2 Lecturers held their audiences spellbound as feathers jumped through the air, water jets glowed, and glasses of spirits were set aflame by the touch of a sword. Many wealthy families bought their own appar- atus, and aristocratic women produced miniature lightning flashes from their fingers and their whale- bone petticoats, or titillated their admirers with a sensational – if rather painful – electric kiss. At the Hanoverian court, electric entertainment replaced dancing; in Edinburgh, myrtle trees were found to blossom earlier after a dose of electricity; while in Paris, electrified animals were found to lose weight (this was attributed to increased perspiration). One early enthusiast was John Wesley, the Methodist preacher, who had learned about electricity from reading a book by Franklin. As Wesley travelled around England with his own electrical machine, he marvelled: ‘What an amazing scene is here opened, for after-ages to improve 3

Description: