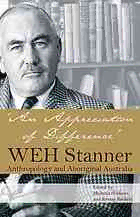

An appreciation of difference : W. E. H. Stanner and Aboriginal Australia PDF

Preview An appreciation of difference : W. E. H. Stanner and Aboriginal Australia

Edited by Melinda Hinkson and Jeremy Beckett First published in 2008 by Aboriginal Studies Press © Melinda Hinkson and Jeremy Beckett in the collection, 2008 © in individual chapters is held by the contributors, 2008 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its education purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act. Aboriginal Studies Press is the publishing arm of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. GPO Box 553, Canberra, ACT 2601 Phone: (61 2) 6246 1183 Fax: (61 2) 6261 4288 Email: [email protected] Web: www.aiatsis.gov.au/aboriginal_studies_press National Library of Australia Cataloguing-In-Publication data: Author: Hinkson, Melinda. Title: An appreciation of difference: WEH Stanner and Aboriginal Australia ISBN: 9780855756604 (pbk.) ISBN 978 0 85575 685 7 (PDF ebook). Notes: Includes index. Subjects: Stanner, W. E. H. (William Edward Hanley), 1905-1981. Anthropologists — Australia — Biography. Aboriginal Australians — Social life and customs. Aboriginal Australians — Social conditions. Dewey Number: 301.092 Printed in Australia by BPA Print Group Pty Ltd Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are respectfully advised that this publication contains names and images of deceased persons, and culturally sensitive material. AIATSIS apologises for any distress this may cause. Cover images: (front) WEH Stanner in his room at University House, Australian National University, c. 1958; (back, L–R) Major WEH Stanner, 2/1st North Australia Observer Unit, c. 1942, AWM, PO4393.001; Stanner at a campfire, Fitzmaurice River, c. 1958; Stanner during fieldwork in the Daly River region, c. 1932. Foreword Bill Stanner’s extraordinary career took him from the bureaucracy to the academy. He had a distinguished career in the British colonial service, and briefly in the Australian department of external affairs. He reached the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Australian Army and commanded the North Australian Observer Unit during World War II. He was a foundation member of the Department of Anthropology at the Australian National University. Bill Stanner was also a central figure in the establishment of what would become the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, an organisation I am proud to currently chair, and was, in fact, the Institute’s first executive member. Stanner had been a tireless critic of the treatment of Aboriginal people since the 1930s, and of the policy of assimilation that dominated the state’s relationship with Indigenous Australia from the 1940s. A result of the 1967 referendum was the establishment of the Council for Aboriginal Affairs, a key body advising on new government policies in relation to Aboriginal people. The council rejected the policy of assimilation in favour of proper recognition of a unique Aboriginal identity, cultural expression, and land rights. Together with Nugget Coombs and Barrie Dexter as co-members, Stanner played a unique role in overseeing reform in Aboriginal Affairs. However, after three decades of bipartisan support for a broad policy platform of choice that the council promoted, the last 10 years has seen processes of attrition, combativeness and outright hostility in Indigenous affairs. During its last term in office, the Howard government was emboldened to implement its true intentions in Indigenous affairs, having secured an unexpected majority in both the House of Representatives and iii Foreword the Senate. Each year from 2004 unveiled a further dismembering of key institutions of indigenous Australia. In 2004 the government disestablished the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission; 2005 saw a renewed attack on the iconic Northern Territory land rights legislation — the high- water mark in Australia in rights for Indigenous people. In that same year the then Minister for Indigenous Affairs Amanda Vanstone declared Aboriginal outstations to be ‘cultural museums’. In 2006 the Aboriginal Land Rights Act (Northern Territory) was amended, leading to a further weakening of land councils, and the introduction of Section 19(a) head-leasing of townships as a mechanism to deliver to Aboriginal people their citizenship entitlements in return for the voluntary alienation of their land. In 2007, just months before being voted out of office, the Howard government made its most controversial act in Indigenous affairs with the declaration of the Northern Territory ‘national emergency’ intervention. Under the Northern Territory Emergency Response legislation the protections afforded under the Racial Discrimination Act (the RDA) to Aboriginal people captured by the new law were suspended and the government asserted that the steps taken under the new law were to be characterised as ‘special measures’ for the purposes of the RDA. For example, the permit system that provided traditional owners with the authority to control who entered their lands was abolished and the compulsory acquisition of all prescribed communities, for five years, was introduced. These and other land-related measures had nothing to do with the child sexual abuse reported by Anderson and Wild’s Little children are sacred report, which provided the government’s stated rationale for launching the intervention, and much to do with pre-conceived ideological positions. It soon became clear that the overarching philosophical intent in the intervention was mainstreaming. When visiting Hermannsburg in August 2007 prime minister Howard told residents that whilst respecting the ‘special place of indigenous people in the history and life of this country, their future can only be as part of the mainstream of the Australian community’ (Australian, 29 August 2007). A subtext of these debates has been about the supposed unviability of remote townships and the possibility of voluntary and involuntary shifting of Aboriginal people to ‘viable’ centres of economic activity. For the first time since land rights was enshrined in Commonwealth legislation, we have faced the spectre of Aboriginal people being forced to leave their land. This is a policy reminiscent of the centralisation prescriptions of the failed assimilation era. Stanner would have found this state-driven, top-down policy-making extraordinarily regressive and destined to fail. His work was exceptionally important in conveying something about the distinctive nature of Aboriginal people’s relationship to their country to a wider Australian audience. In 1968 Stanner delivered his Boyer Lectures, After the Dreaming, which are still well iv Foreword recognised today, forty years on. In the lecture titled ‘Confrontation’ (Stanner 1969, p. 44) there is a particularly beautiful passage: No English words are good enough to give a sense of the links between an Aboriginal group and its homeland. Our word ‘home’, warm and suggestive though it may be, does not match the Aboriginal word that means ‘camp’, ‘hearth’, ‘country’, ‘everlasting home’, ‘totem place’, ‘life source’, ‘spirit centre’ and much else. Our term ‘land’ is too spare and meagre. We can scarcely use it except without economic overtones unless we happen to be poets. Stanner was spot on. When Aboriginal people talk about ‘country’ we mean something very different from the conventional European understandings. We might mean homeland or tribal or clan area. But we are not necessarily referring to a place in a merely geographical sense. Rather, the word ‘country’ is an abbreviation of all the values, places, resources, stories and cultural obligations associated with that area. Certainly, to talk of country is to talk of its resources: the uses to which these might be put, and their proper distribution. In this sense, to understand country is also to understand its crucial importance to the customary Indigenous economy and governance. However, the word best describes the entirety of a people’s ancestral inheritance. It is Place that gives meaning to creation beliefs. The stories of creation form the basis of Indigenous law and explain the origins of the natural world. To speak of country is to speak both of the economic uses to which it may be put and of a fundamentally spiritual relationship that links the past to the present, the dead to the living and the human and non-human worlds. Country is centrally about identity. Australia’s Indigenous peoples have fought hard to protect and preserve our countries and our identities since the first white settlements emerged on the NSW coast in the late 1780s. In the Northern Territory the persistent struggles of the Yolngu people of north-east Arnhem Land culminated in the Woodward inquiry whose findings and recommendations formed the basis of the first legislative regime of land rights based on freehold title in Australia. The Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act of 1976 was the first legislation in Australia to establish a land claim process by which traditional owners could claim various areas of land not through petition but as their right. Hence, the report of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody said of Northern Territory land rights that: The result has been a fundamental shift in the position of Aboriginal people. Despite many ongoing problems, Aboriginal people now have an independent economic, political, and symbolic base for action. They have moved at least in part to a position of negotiation with the state. The importance of this is demonstrated in the growth of v Foreword strong and effective Aboriginal organisations, and the extent to which Aboriginal people now have to be taken seriously as a significant group within Northern Territory society. However, the ‘reforms’ of the Howard government have steadily chipped away at these historic achievements, hard won over so many years by Aboriginal people and their supporters. Stanner predicted that a day would come when Aboriginal people might want to sell their land. The main message to be drawn from his writings on Aboriginal policy is that Aboriginal people should be allowed to make informed and realistic choices about their futures, not have decisions thrust upon them. The previous government sought to force changed land tenure arrangements upon traditional owners through the implementation of the 99-year leasing arrangements. I and others have pointed out that these changes were not required to enable the kinds of housing provision and economic development opportunities the government sought to encourage. Paradoxically, as we celebrated the fortieth anniversary of the referendum in 2007, Indigenous affairs reached a nadir. Where does one go from a nadir? There is some cause for optimism that the new Rudd government will take a more consultative approach. As I write there is much activity, much reviewing and also considerable uncertainty in the field of Aboriginal affairs. Since elected in November 2007 the Rudd government has announced it will endorse the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, it will establish a new Indigenous representative body, it has launched a review of the NT intervention, and a review of a key NT Aboriginal statutory authority the North Land Council. A case sits before the High Court challenging the Commonwealth’s compulsory acquisition of prescribed areas, possibly without just compensation. The outcomes of these various activities are far from assured: Will the review of the intervention recommend that NT emergency response laws pass the scrutiny of the RDA? Will the High Court find that the compulsory acquisition of Aboriginal land to provide public housing and services is unconstitutional? Will the government continue to support Aboriginal people who aspire to continue living on their customary estates or will it endorse the neo-liberal prescriptions of migration and mainstreaming? Clearly much has changed in the last half century, but there are obvious parallels between the assimilation policies of the mid-twentieth century and the neo-liberal prescriptions of the present. Both impose a future on Aboriginal people that seeks to speak on their behalf as to what best represents their future prospects. Both have neither mechanism nor room to hear from Aboriginal people as to what their aspirations might be, and how they might differ from those of mainstream Australia. This seems a risky vi Foreword strategy for both remote-living Indigenous people and wider Australia alike. At the very time when climate change looms as the major threat to the very foundation of the neo-liberal paradigm, Aboriginal people are being asked to walk away from activities and ways of life that can contribute considerably to the maintenance of extremely biodiverse regions as well as carbon abatement. When Stanner was concerned with choice his focus was fixed firmly on Aboriginal benefit, although he did identify the cost to the nation of continued Indigenous disadvantage. But today the stakes are far higher than Stanner could possibly have imagined. By allowing remote-living Aboriginal people who wish to remain on and manage their country the choice to do so, we can see that their environmental management regimes might have local, national, and even global benefits. These benefits remain, as yet, unrecognised and unimagined by the nation. Surely, in this time of great uncertainty, this is the sort of choice we as a rich nation should be encouraging, for Aboriginal people as well as for all Australians? Mick Dodson August 2008 vii Contents Foreword iii Illustrations xi Acknowledgments xiii Contributors xv ‘Going more than half way to meet them’: On the life and 1 legacy of WEH Stanner Jeremy Beckett and Melinda Hinkson part 1. diverse fields 1. ‘A chance to be of some use to my country’: Stanner 27 during World War II Geoffrey Gray 2. Stanner and Makerere: On the ‘insuperable’ challenges 44 of practical anthropology in post-war East Africa Melinda Hinkson 3. WEH Stanner and the foundation of the Australian Institute 58 for Aboriginal Studies, 1959–1964 John Mulvaney 4. Stanner: Reluctant bureaucrat Barrie Dexter 76 part 2. in pursuit of transcendent value 5. Frontier encounter: Stanner’s Durmugam Jeremy Beckett 89 6. Journey to the source: In pursuit of Fitzmaurice rock art 102 and the High Culture Melinda Hinkson 7. Stanner’s veil: Transcendence and the limits of scientific 115 inquiry Peter Sutton