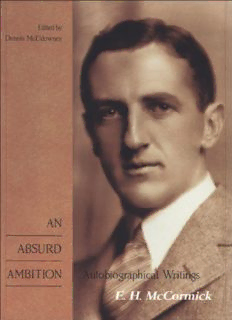

An Absurd Ambition PDF

Preview An Absurd Ambition

I never wanted to be an engine-driver or an explorer or an All Black. I had no desire to be a bootmaker like my lather or a carpenter like most of my uncles or a farmer like some of my cousins. But even in my school-days I longed to be a writer and in the barren years that followed I went on cherishing the absurd ambition. Eric McCormick was, from about 1940 till his death in 1995, one of New Zealand’s most distinguished writers and scholars. He wrote several important biographies, his Letters and Art in New Zealand was a landmark work and he pioneered the appreciation and the study of the painter Frances Hodgkins. With dry wit, and in a trademark elegant style, his shrewd observations of literary and artistic behaviour provided fascinating insights into the cultural history of New Zealand. In An Absurd Ambition Dennis McEldowney brings together a remarkable collection of autobiographical fragments to create a moving and coherent ‘autobiography’. Piecing together finished and unfinished essays, letters and diary entries, he follows McCormick’s personal and intellectual development, from his childhood in Taihape, to school and university in Wellington and Cambridge, and through his wartime experiences and role as editor of Centennial Publications. AN ABSURD AMBITION AN ABSURD AMBITION AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL WRITINGS E. H. McCormick Edited by Dennis McEldowney First published 1996 This ebook edition 2013 AUCKLAND UNIVERSITY PRESS University of Auckland Private Bag 92019 Auckland 1142 www.press.auckland.ac.nz Main text © Estate of Eric McCormick 1996 Arrangement and editorial matter © Dennis McEldowney 1996 This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act no part may be reproduced by any process without the prior permission of Auckland University Press. eISBN 978 1 86940 798 8 Publication is assisted by Acknowledgements are due to Annabel Fagan and Heather Leggat for providing photographs. CONTENTS Introduction Brief Chronology and Bibliography 1 The Emporium 2 Wellington 3 Apollo in Taihape 4 A Sentimental Education 5 Greek History, Art and Literature 6 Sole-Charge 7 The Custom of the Country 8 Cambridge 9 Dunedin 10 Centennial 11 The Jumpers 12 ‘In a State of Intoxication’ 13 Via Suez Epilogue Sources Index INTRODUCTION Dennis McEldowney In the spring of 1993, Eric McCormick telephoned to ask me, in that hesitant, constantly rephrasing manner which was one of several traits he shared with Henry James, whether I would consider writing a book about his sister Myra, who had died the previous June. She and Eric had lived together for fifty years, except for intervals when one or the other was away, and the final two years when Myra, in the last stages of Alzheimer’s Disease, was looked after in hospitals and nursing homes. In countless ways Myra had provided the environment and dealt with the practical issues which enabled Eric to be, for much of that time, a full-time writer. After they moved to Auckland from Wellington in 1947, they lived for eight years in Grafton Terrace, a short street which has long since been sacrificed to the motorway, in a house which they at first rented from the University Librarian, Alice Minchin, and later bought from her. As Myra neared retirement, in 1954, her work as a public health nurse, mainly among Maori families, took her to Harrybrook Road in Green Bay. There she saw a site, overlooking the Manukau Harbour, on which a couple had started to build a house while living in a two-room bach. They had got no further than the foundations when they ran out of money. Myra bought the property and after her retirement, while Eric was in Europe for nearly two years, she moved into the bach, and planned a house which used most though not all of the original foundations. By the time Eric returned, Myra was living in the newly erected house, and the bach, only three or four metres from the house, was available for Eric. There he slept and worked, and could make light meals when he wished to, though he often ate with Myra. They were in partnership, despite the fact that many of Myra’s interests were quite different from Eric’s. On occasion she acted as his research assistant, especially when he was overseas and needed a reference from an Auckland library. In his grief after Myra’s death, Eric accused himself of having taken her for granted: his call to me was an attempt to make amends. He had admired my book about my wife, Shaking the Bee Tree, and hoped I might do something similar for Myra. I was doubtful about the prospect, but owed so much to Eric in many ways that I could not brush it aside. Nor, in view of his frail health, could I plead pressure of work (though that could have been justified) and suggest waiting for a couple of years. I said I would visit him and look over the available material. On weekly visits for the rest of the year we looked through records, beginning with photographs and moving on to written material. Alas, it soon became clear that the makings of a book such as he desired did not exist. Apart from photographs, very little was documented about Myra’s childhood and early life, or about her nursing career. Even Eric’s reminiscences could not fill the gaps. They had not been close when young, for which Eric assumed the two-year difference in their ages was sufficient explanation. He could say little more than that she was there. What did become clear, however, was the amount of autobiographical writing Eric himself had done, little of which had been published. Eric could no longer remember everything he had written, let alone where it all was, though he was clear enough about the contents when they were found. At first he was wary of letting me loose among his papers, but as his confidence grew he began to allow it and, with Eric constantly at my side, I went systematically through the papers stowed in filing cabinets, chests of drawers, desk drawers, desk top, and bookshelves, all in his two-roomed bach (though he was now living in the house). What I found were finished essays, uncompleted essays, letters written in response to specific queries, particularly about his time in Cambridge, and fragments of all kinds. They covered most of his life from birth until the age of fifty: his childhood, secondary schooling in Wellington, teachers’ training college and university, teaching at sole-charge schools in rural Nelson, the scholarship to Cambridge; his underemployed years in Dunedin, Centennial Publications, war experiences, and the excitement with which he began his biographical work on Frances Hodgkins. Some of this material existed in up to seven handwritten drafts, differing slightly but occasionally significantly. He also showed me four volumes of a journal kept intermittently from 23 December 1923, when he was seventeen, until 14 June 1989, three days before his eighty- third birthday. Notable among his published essays were The Inland Eye: A Sketch in Visual Autobiography (1959), a booklet based on a talk he had given to the Auckland Gallery Associates; ‘Apollo in Taihape’, published in the New Zealand Listener in 1966 and later in Bridget Williams’s miscellany, The Summer Book 2; and ‘Beginnings’ in Islands 22 (1978). During my time at the Auckland University Press I urged him several times to let us publish a collection of his essays, autobiographical, literary, and general. His answer was always that they would require a great deal of revision, that only he could do it, and that he had more urgent work to complete. Now that he was no longer capable of sustained literary work, I proposed that with his active help I should edit his autobiographical writings. To this he acquiesced, if only as a second-best to a book on Myra. A real start to the work was delayed when, just after Christmas 1993, Eric became ill, mainly from exhaustion and malnutrition (he had been receiving meals-on-wheels, but finding them unappetising had fed them to a neighbour’s dog), and was moved to an ‘apartment’ in Powley House, a large establishment for the elderly in Blockhouse Bay. After about a month he was able to return home with an all-day helper from a service attached to Powley House. (He was still alone at night.) For the greater part of 1994 I spent every Friday afternoon with him and shared his evening meal, by courtesy of the home helpers. I searched for further material, put it in chronological order, clarified obscure points with him, taped reminiscences, especially where there were gaps to be filled or unfinished stories to be completed, and discussed the progress of my work. Since he seldom remembered from Friday to Friday exactly what we had been doing, much of this had to be repetitious. Eventually, on red-letter days, I would have the draft of a chapter or part of a chapter to read to him, through the medium of his cumbersome ‘hearing enhancer’; then I would leave the copy with him for further consideration. In this way, by the end of the year, he had read or heard and approved of all but the last three chapters of this book. He could seldom resist disparaging remarks about his own writing (‘Too wordy’ was his most frequent complaint), and often corrected my facts or assumptions. Other regular visitors were there on other days of the week, notably Maurice Shadbolt and Elspeth Sandys, Linda Gill, Jacqui Fahey, Michael Smither, and Roy Hughes (whose parents had laid the foundations for Myra’s house); they all reported his enthusiasm for our book. Near the end of 1994, however, after several night-time falls and a bout of pneumonia for which he was admitted to Auckland Hospital, he returned to Powley House, where his deterioration was so rapid before his death on 23 March 1995 that he was no longer able to take an interest in what I was doing. During his last weeks Eric believed he was sharing an ocean voyage with Myra. Why else would so many people be sitting in rows doing nothing and waited on by people in uniform? He identified as Myra a succession of old ladies among his fellow residents of Powley House. A detailed note on sources is printed at the end of the book, so only a few general remarks are needed here about the variety of methods used in composing the chapters. Two, ‘Apollo in Taihape’ and ‘“In a State of Intoxication”’ (the

Description: