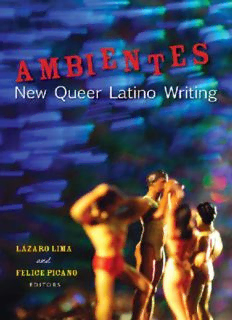

Ambientes: New Queer Latino Writing PDF

Preview Ambientes: New Queer Latino Writing

Ambientes E E S N M B I T A New Queer Latino Writing Edited by and The University of Wisconsin Press The University of Wisconsin Press 1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059 uwpress.wisc.edu 3 Henrietta Street London WCE 8LU, England eurospanbookstore.com Copyright © 2011 The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any format or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press, except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews. 1 3 5 4 2 Printed in the United States of America A version of “Magnetic Island Sueño Crónica” by Susana Chávez-Silverman first appeared as “Currawong Crónica” in Chroma: A Queer Literary and Arts Journal6 (Spring 2007), reprinted by permission of the author; “Haunting José” by Rigoberto González first appeared in Men without Bliss(Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), reprinted by permission of the publisher; a version of “Shorty” by Daisy Hernández was first published in Sinister Wisdom74: Latina Lesbians (2008), reprinted by permission of the author; “Arturo, Who Likes to Shave His Legs in the Snow” by Lucy Marrero first appeared in Alchemist Review30 (April 2007), reprinted by permission of the author; “Kimberle” by Achy Obejas first appeared in Another Chicago Magazine 50 (July 1, 2010), reprinted by permission of the author; “I Leave Tomorrow, I Come Back Yesterday” by Uriel Quesada first appeared as “Salgo mañana, llego ayer” in Lejos, tan lejos(San José: Editorial Costa Rica, 2004), translated into English by Amy McNichols and Kristen Warfield, reprinted by permission of the publisher; “La Fiesta de Los Linares” by Janet Arelis Quezada first appeared in Women Writers(Winter 2001), www.women writers.net, reprinted by permission of the author; “Porcupine Love” by tatiana de la tierra first appeared as “Amor de puercoespín” in Dos orillas: Voces en la narrativa lésbica(Barcelona: Egales Editorial, 2008), edited by Minerva Salado, and in English in Two Shores: Voices in Lesbian Narrative(Barcelona: Grup E.L.L.Es, 2008), edited by Minerva Salado, reprinted by permission of the author; “Dear Rodney” by Emanuel Xavier first appeared in If Jesus Were Gay and Other Poems(Bar Harbor, ME: Queer Mojo/Rebel Satori Press, 2010), reprinted by permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ambientes: new queer Latino writing / edited by Lazaro Lima and Felice Picano. p. cm. ISBN 978-0-299-28224-0 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-299-28223-3 (e-book) 1. Hispanic American gays—Fiction. 2. American fiction—Hispanic American authors. 3. Homosexuality in literature. 4. Gays’ writings, American. I. Lima, Lázaro. II. Picano, Felice, 1944– PS647.G39A46 2011 813´.6080868073—dc22 2010041228 Contents Editors’Note:The Name of las Cosas vii Preface ix Acknowledgments xiii Introduction: Genealogies of Queer Latino Writing 3 Kimberle 14 Pandora’s Box 27 Shorty 45 Puti and the Gay Bandits of Hunts Point 57 - Porcupine Love 75 The Unequivocal Moon 84 Dear Rodney 89 This Desire for Queer Survival 96 . La Fiesta de Los Linares 112 v Malverde 126 Aquí viene Johnny 137 Haunting José 144 Imitation of Selena 152 Magnetic Island Sueño Crónica 159 - I Leave Tomorrow, I Come Back Yesterday 165 Six Days in St. Paul 178 Arturo, Who Likes to Shave His Legs in the Snow 196 Contributors 201 vi Editors’ Note The Name of las Cosas Ambientes: New Queer Latino Writing seeks to provide a timely and representative archive of queer Latino literary and cultural memory in order to enact a more inclusive “American” literary canon that can apprehend the present and the future of queer Latino literary practice. We have assembled a diverse and representative sample of contemporary queer Latino writing in order to provide a source of pleasure for readers as well as a resource for instructors and students who have too often been deprived of this crucial though underanalyzed component of national literary culture. Consistent with our belief that Spanish is not a foreign language in the United States, we have not italicized words in Spanish. Those words that do appear in the anthology in italics, whether in Spanish or not, have been italicized by the authors and usually connote emphasis but not a different linguistic register or the notion that Spanish is a foreign language in this country. In keeping with standard Spanish grammatical usage, the singular “Latino” or plural “Latinos” in the preface and the introduction refer to both sexes and allow us to avoid the graphically more sluggish “Latina/o,” Latina/os,” or “Latin@s.” In doing so we also suggest the obvious: to believe that graphic characters can reform inequality, linguistic or otherwise, is a fatuous proposition if structural inequalities are not concomitantly addressed. Further, taking Spanish seriously in the United States requires understanding its structures, its speakers, the colonial legacies that haunt both, and why Spanish continues to be classed as “inferior.” When we consider that the United States is the third-largest Spanish-speaking country in the world (out of twenty-one countries whose official language is Spanish plus the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico), then we must confront the language issue with urgency and creativity. In both the preface and the introduction we refer to Latinos as persons of Latin American ancestry living in the United States. Certainly, Spanish is not the only language in Latin America, but r egrettably vii majority culture still incorrectly racializes and classes many Latinos as “foreign,” and, too often, as just Spanish speaking (read: “Mexican”). When we consider that, aside from Mexican and Central American migration and immigration to the United States, Brazilians constitute the third-largest migrant or immigrant group, then it becomes expedient to include Brazilians—who often have to learn Spanish and, eventually, English to enter local economies—under the admittedly less than precise but necessary rubric “Latino.” We received many fine submissions for this anthology in both English and Spanish. The best of both were included in Ambientes. Those submitted in Spanish have been translated into English in order to entice a broader readership into seeking out the Spanish originals, perhaps even encouraging them to learn the other unofficial national language. As readers demand more of queer Latino writing and cultural production, we hope that the Latino Brazilian experience also makes its way into the futures of Latino literary and cultural production. Finally, we hope you enjoy reading Ambientes: New Queer Latino Writing. Please visit the book’s website for research ideas, additional readings, links to authors’ websites, as well as teaching suggestions and class projects based on Ambientes: www.myambientes.com. ’ viii Preface The two young men at the back of the library had been there early, and they dawdled after everyone else at my reading and talk had left. They’d been silent and attentive throughout, almost extra-alert, but now that they were standing before me they relaxed and they gushed. Among the things they said in their enthusiasm was this: “We’re so proud to have someone of Latino extraction as an openly out gay writer.” I looked at them more closely. This close up, I could see that both appeared to be Latino. Clearly, they thought that I, with my vowel- filled name and my large brown eyes, was also Latino. And, in a way, I am. My father was born in the town of Itria in an area of Central Italy about forty miles east of Rome, the area known as Latium, from which the Latin tongue took its name. So, in fact, he, and I through him, was an original Latino. Only I’m not Latino the way those young men thought: they felt proud of having a Latino gay man so out, so prominent, to represent them. A few generations ago, I might have been one of those young men, attending a rare reading of an Italian American author. Those certainly were rare in the past, and people of Italian heritage were mostly unassimilated into the American mainstream until the middle of the last century, in a way similar to how many younger Latinos feel to not be part of our wider culture today. As the result of discovering an unsolved murder in my family—through being a writer—I’ve been delving into my own family history. In New England in the 1920s and early 1930s, anti-Italian sentiment reached an all-time high, especially after the farce of the Sacco-Vanzetti trial. Elderly people in Rhode Island told me in interviews that as teens they would have to go to church and school in groups no smaller than ten because they were so often physically attacked. While still a youth, I personally remember experiencing anti- Italian prejudice, including at an Ivy League school. During an interview for a Woodrow Wilson graduate scholarship at Princeton in 1964, as I ix

Description: