Algeria - Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training PDF

Preview Algeria - Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training

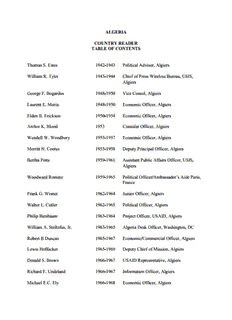

ALGERIA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Thomas S. Estes 1942-1943 Political Advisor, Algiers William R. Tyler 1943-1944 Chief of Press Wireless Bureau, USIS, Algiers George F. Bogardus 1948-1950 Vice Consul, Algiers Laurent E. Morin 1948-1950 Economic Officer, Algiers Elden B. Erickson 1950-1954 Economic Officer, Algiers Archer K. Blood 1953 Consular Officer, Algiers Wendell W. Woodbury 1955-1957 Economic Officer, Algiers Merritt N. Cootes 1955-1958 Deputy Principal Officer, Algiers Bertha Potts 1959-1961 Assistant Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Algiers Woodward Romine 1959-1965 Political Officer/Ambassador’s Aide Paris, France Frank G. Wisner 1962-1964 Junior Officer, Algiers Walter L. Cutler 1962-1965 Political Officer, Algiers Philip Birnbaum 1963-1964 Project Officer, USAID, Algiers William A. Stoltzfus, Jr. 1963-1965 Algeria Desk Officer, Washington, DC Robert B Duncan 1965-1967 Economic/Commercial Officer, Algiers Lewis Hoffacker 1965-1969 Deputy Chief of Mission, Algiers Donald S. Brown 1966-1967 USAID Representative, Algiers Richard E. Undeland 1966-1967 Information Officer, Algiers Michael E.C. Ely 1966-1968 Economic Officer, Algiers Fernando E. Rondon 1966-1967 Principal Officer, Constantine 1967-1968 Consular Officer, Algiers Edward L. Peck 1966-1969 Principal Officer, Oran Laurent E. Morin 1967-1970 Economic Officer, Algiers Arthur L. Lowrie 1968-1972 Algeria Desk Officer, Washington, DC Allen C. Davis 1970-1973 Political Officer, Algiers Howard R. Simpson 1972-1974 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Algiers Charles Higginson 1973-1975 Economic Counselor (US Interests Section) Algiers Larry Colbert 1973-1976 Consul, Officer in Charge Oran, Algeria Ronald D. Flack 1974-1976 Commercial Attaché, Algiers Richard B. Parker 1974-1977 Ambassador, Algeria Lambert Heyniger 1976-1978 Principal Officer, Oran, Algeria Ulric Hayners, Jr. 1977-1981 Ambassador, Algeria Richard Sackett Thompson 1980-1982 Political Counselor, Algiers Edmund James Hull 1980-1982 Algeria Desk Officer, Washington, DC Barbara H. Nielsen 1981-1983 Cultural Affairs Officer, USIS, Algiers Michael Newlin 1981-1985 Ambassador, Algeria Ann B. Sides 1985-1987 Consular Officer, Oran, Algeria Haywood Rankin 1992-1994 Deputy Chief of Mission, Algiers Nancy E. Johnson 1994-1996 Political Officer, Algiers Donald F. McHenry 1998 Participant, Eminent Persons Group for the Secretary General of the UN, Algeria THOMAS S. ESTES Political Advisor Algiers (1942-1943) Thomas Estes was posted to Greece, Washington, DC, and the Upper Volta as a Foreign Service officer. He was interviewed in 1988 by Ambassador Dwight Dickinson. ESTES: I was off to Algiers. It was there, incidentally, that I was commissioned an FSO, having passed the oral examination while in the Department. Allied Force Headquarters, of course, was a totally military organization with no previous experience in dealing with a civilian section (We became known as POLAD -- Political Adviser). Fortunately, Ambassador Robert Murphy was General Eisenhower's political adviser and he arranged for us to have places to live and to draw rations. If you want me to go on with this a bit... Q: Yes, tell us something about... ESTES: In Algiers we were bombed by the Germans and the Italians. In Bangkok we'd been bombed by the British -- a unique experience, being bombed by both sides. I shared an apartment with J. Holbrooke Chapman, an FSO who had been my immediate supervisor in Bangkok, and at night during an air raid we would get up and go to a shelter across the street. Aside from these raids it was fairly routine work for me as the junior officer. As you can recall, the junior officer did all the administrative work in those days. WILLIAM R. TYLER Chief of Press Wireless Bureau, USIS Algiers (1943-1944) William Tyler was born in Paris, France in 1920. He served with the United States Information Agency in France and Washington, DC. He then entered the Foreign Service and served in Washington, DC, the Netherlands, France, and Germany. He was interviewed by Charles Stuart Kennedy in 1987. TYLER: John Houseman called me up and said you are going to Allied Force Head Quarters in Algiers in charge of Radio. He said "I was going but that has been indefinitely postponed." I said, "Why did you pick me?" He said, "well I'll tell you, there were 3 or 4 people on the short list, anyone of whom might have gone, but we wanted somebody that had qualities, somebody who we thought not only well qualified but also a son-of-a-bitch." He used those words. I said thanks for the compliment. He said, "well you know what I mean." And I said, "alright, I'll do what I can." Then he said, "get your uniform and don't talk, don't tell anyone where you are going", and I said I wouldn't. I didn't even tell my wife. She was in Boston, we were living in Dedham. Houseman said that when the time comes, you will have at the most 36 hours notice before you leave. That will give you a chance to see your wife if she doesn't come down to see you before you go. I was staying at the Seymore hotel on 44th street. Q: When you went to Africa, you were stationed in Oran? TYLER: No, I arrived in Oran. I was there for a couple of days then was flown to Algiers. Q: What was your position in Algiers? TYLER: Well, in charge of the Radio Division. The Radio Division was the psychological branch of the Allied Forces Head Quarters. Q: Was there a difference in the type of work you were doing there than what you were doing in New York? Was the radio work in Algiers tactical more than strategic? TYLER: No, the same issues. It was continuing the same work. Q: Was it also aimed at the same Western European countries, say Spain, Italy and France? TYLER: It was the Western Mediterranean area, which included Spain, Italy, France, but not Greece. But the record is fuzzy in my recollection, whatever the programing was, it was aimed immediately at two targets, one the local population in the country and another, the German troops, anything that could effect their morale and diminish their fighting spirit. Q: So in this regard you were performing more of a tactical type of radio as opposed to talking to the populace at large? TYLER: I was in the theater of operations. I was being bombed in Algiers, until after the Sicilian landings when the German airbases had to withdraw. But until July-August 1943, when I arrived in Algiers, we were under wartime, blackout conditions. Q: What type of people did you have working for you there. TYLER: A lot of former colleagues from the OWI. And there were people who I thought were simply devoted heart and soul to the Allied cause in support of our positions and our policies. I myself never concealed the fact that I was very strongly in support of de Gaulle, not as a political figure but as the one rallying point in France for resistance that could have in due course a determining effect on French opinion. Bob Murphy was there, and he was a friend, my father knew him when he was consul in Paris. Bob Murphy naturally was an official of the State Department, and I was OWI. There were the OSS people, Ridgway Knight, Julius Holmes, Harry Woodraw, Selden Chapin and Robert McBride, people like them. I was not with the OSS. They were civil affairs officers. We were all for the government but they were in the government framework. I was OWI, but I was not responsible to them. Q: What about the coordination, you were in the military command, we have an overall, sort of a dual political structure with MacMillan and Murphy, Harold MacMillan being the British administrator, Murphy being the U.S. advisor. Who gave you orders? TYLER: That's a very good question. The answer is I can't remember. I tell you, by the time we got our directives from the OWI in Washington, very often those directives were no longer topical. After a delay of several days, so in a sense, I was in charge of radio, I broadcast myself a few times but my administrative responsibility was for script writing, so I gave up broadcasting in French. Actually looking back on it its staggering the latitude I had. Q: I think this is true in any wartime situation, it happens. Did you attend staff meetings? TYLER: I had my own meetings in the building, the Maison de l'Agriculture in the Bulevard Bourbon in Algiers. I had the Radio Office staff meetings, but small meetings of the people in charge of units. But, I don't remember there being any conflict in policy except that I knew Bob Murphy where he stood was somebody who was naturally carrying out very closely and rightly the President's policy after all he was our President. I never conflicted with his policy but I always insisted on emphasizing as much as possible, not de Gaulle's military roles but the importance of supporting de Gaulle as the spirit of France. Q: What about Giraud? TYLER: Well, that of course, I saw Giraud in Algiers I was present at the first meeting with him and de Gaulle with the press present. Q: The wonderful handshake picture. TYLER: I was there. Well, Giraud was made mincemeat of by de Gaulle. Giraud I think is an honorable and patriotic man who just didn't have what it took to create a position of leadership, a rallying point. In a way I was too close to it all to have a true perspective on it. But it is quite clear that Giraud would not be able to rally enough support to withstand the strong and increasing role of de Gaulle. Q: Then in Algiers, dealing with German or Italian troops... TYLER: We had interrogation teams. Q: You would get information from them? TYLER: Oh Yes. Q: It is always difficult in broadcasting, where you're sending out, you dream things up in your head and you try to use your knowledge of the country and all that but how did you measure your effectiveness? TYLER: I had no means. Q: How about prisoner interrogation did you get anything from them? TYLER: Yes, occasionally we received reports. What we were doing in North Africa was peanuts compared with what BBC was doing and Voice of America was doing from the states. But we did have the advantage of broadcasting from these two antennae, they were balloon rigged antennas, there was Hippo and I forget the other name, rigged up outside of Algiers. So, our medium wave broadcasting from Algiers only had the advantage that it was a voice coming from nearer than from across the Atlantic, but it was a very small beer compared to the mass of information coming from Britain and the United States. Q: With the BBC, was there was much cooperation, did you feel it was a role model or a rival? TYLER: Oh I never felt it was a rival. I never felt any competition. BBC was so infinitely better, covering the whole of Europe. Q: To go back a bit, was the Voice Of America under the OWI? TYLER: Yes. Q: Were you called the Voice Of America? TYLER: No. We called ourselves the Voice of the United Nations Radio Allied Force Head Quarters in Algiers. Q: But when you were in New York you called yourself Voice Of America? TYLER: Yes. Until December 1943, I was in charge of Radio Allied Force Headquarters, and I used to go regularly go to AFHQ, I forgot the name of the hotel in Algiers where General Eisenhower was. But then of course, he moved to London, AFHQ moved to London for preparations for Overlord (the invasion of Northern France). The void created by the move was immediately taken over by Seventh Army Planning HQ for "Operation Anvil", which was to take place in the south of France following (the landing of Salerno). Salerno followed after the conquest of Sicily. General McChristal was the US army officer in charge of psychological warfare branch of the HQ; he succeeded Colonel Hazeltine. And General McChristal called me up and said, "I'd like to see you", and I said, "General I'm on my way." And he said, "I'm taking you up to Bouzarea, above Algiers to the west and I'm going to introduce you to the officers and staff in planning HQ for these landings in Southern France." Later on I met General Patch the Seventh Army commander and his senior staff. My particular military anchor was then Colonel Quinn, who later became a lieutenant general, and a mighty fine Irishman. Under him was his deputy, Bob Bruskin. General McChristal said to all the people, he made me stand up there with him and said, "I want you all to know Bill Tyler, because he will be working under Colonel Quinn and Colonel Bruskin for the public affairs, psychological warfare side of the preparation of the landings and for the landings themselves." I got the fullest cooperation. There I was, a measly civilian, but they gave me full cooperation. I was in charge in drawing up the plan for the press, radio and leaflet side of the preparation of the landings. Q: Was this the landing at Salerno? TYLER: No, the main landing in Southern France. Q: Oh, this was Dragoon? TYLER: Well, it started out by being Anvil then ended up being Dragoon. From January 1944 until our operations which followed of course much later than Overlord, the final landing was August 15. Q: After the landings did you go into France? TYLER: Yes, but much after the landings. It was a great disappointment to me being the fellow in charge of the whole thing I had the enormous interest and responsibility of planning the preparations, I had been given the fine sounding title of Chief Psychological Warfare, West Mediterranean. I was in charge of leaflets as well as radio, and also the plans for the public affairs side of the landing. All the hardware, the number of men, all the people of the press side, the radio side that had to go in following the landing. I worked on them of course, then I went to Caserta [outside Naples] where the Headquarters was and I saw General de Lattre de Tassigny, we had become friends. Eve Curie, the daughter of the Curies, was on his staff. Its incredible looking back on it, I can hardly believe it all happened. I went to see General de Lattre de Tassigny, in Naples. I also had to arrange work with the French commissioner for information who was Henri Bonnet in the provisional government in Algiers. Henri Bonnet was in charge of the whole press and special relations side. Again, my odd background helped because Bonnet knew my father. I knew Rene Massigli, the commissioner of the interior, I had contacts, easy contact, between their headquarters and its successor, the planning headquarters of the French on nonmilitary matters. GEORGE F. BOGARDUS Vice Consul Algiers (1948-1950) George F. Bogardus was born in Iowa in 1917 and graduated from Harvard University in 1939. He served in the U.S. Army in 1941 and joined the Foreign Service in 1941. In addition to Algeria, Mr. Bogardus served in Canada, Kenya, Czechoslovakia, Algeria, Germany, and Vietnam. He was interviewed on April 10, 1996 by Charles Stuart Kennedy. Q: This would have still been 1948? BOGARDUS: That's right. It was still a French regime at that point. In fact, Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia were -- Algeria was technically part of France. Morocco was a kingdom and Tunisia a republic. My stay there in Algiers was very -- We spoke French with everybody, of course, whereas we had been speaking mainly German or English in Prague. My stay there was cut short, less than two years until 1950 for the following reasons. Following general instructions from the Department, USAID was a potential around the world, especially in an underdeveloped country. They had encouraged us, not only for that reason, but just in general, to make contact with the opposition. The opposition in North Africa were the Arab and the Muslim potential rebels. The French in charge were the very right wing pieds noirs. Consul General George Tait authorized me to meet twice with the most moderate of the Muslim opposition, Ferhat Abbas, who had a French wife. He was also a dentist with a French education. So, he wasn't really rabid. There were several others who were really rabid about pushing the French into the ocean. But I had a couple of talks with his aide in my home next to the St. George Hotel regarding USAID potential and how it might be used and that sort of thing, very innocuous and never a commitment. Then, however, finally, there was a small notice in Le Monde newspaper in Paris about "What's going on with this secret meeting of this American Vice Consul in Algiers?" Elim O'Shaughnessy, who was the desk officer at that point, was hyper-sensitive about it, I thought, but he told me later that it came across his desk that they were looking for people for economic training, and I had indicated an eventual interest. So, he put me in for that. The other thing that happened was that I had scored what I thought was a real intelligence coup regarding foreign cryptography of another government and bucked that in with the label "top secret." I thought top secret was the absolute top. Well, it turned out that there were more copies of top secret things going around Washington than you might think. It never possibly occurred to me at that point that going as high as that there was really no danger at all. The word came back, "Leave that to the CIA." We did have a CIA man there and I turned it over to him. I won't be any more precise than that, but when I got back, Ambassador Llewellyn Thompson, who was Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, sent for me. He chewed me out for doing that, of all things. He said, "Never ever mention this again." Well, I haven't mentioned the core of it, not really even told you. But that's what it was. I haven't said anything to anybody all these years. It wouldn't matter at all now. LAURENT E. MORIN Economic Officer Algiers (1948-1950) Laurent Morin was born in Augusta, Maine in 1920. As a Foreign Service officer, he served in France, Japan, Washington, DC, and Iraq. He was interviewed in 1992 by Charles Stuart Kennedy. Q: Your first assignment was to Algiers. Was that right? MORIN: Yes. Q: From 1948-50? MORIN: Yes. I might introduce that by saying that at the commencement exercise we had before we graduated from the basic officers course, General Marshall, who was then Secretary of State, was the speaker. He also gave out the diplomas. As I went through the line, he shook my hand, gave me my diploma, and said, "Son, where are you going?" I said, "I've been assigned to Algiers, sir." And he said, "Algiers hey, that's the St. George Hotel. Good luck to you." Well it was for me because I ended up living there. The St. George had been the headquarters for the American military in North Africa...Eisenhower's headquarters, etc. I must say it was a fancy hotel but difficult because we were quite poor in those days. We didn't have many of the allowances that you have now. We had a little girl at that time and we couldn't go downtown for supper because it was too late for her, but we couldn't afford to eat in the dining hall at the St. George, as it was just too expensive for us. But we developed a scheme. We would order room service and the waiter would come up, bring in his table (we had a suite), and lay out the linens, plates, etc. and then he would ask, "Madam, are you going to have the soup tonight?" We always ordered the menu fixe, just one meal every night for the two of us. That was all we could afford. And the waiter would dish it out, very formally, one course, to Ann and the next to me. We found Algiers was a real colony in those days. This was a complete French society on the backs of the native population. The French had everything. It was not like in many of the other colonies I have been to. The French had all the jobs all the way down. You found the garage mechanics, the waiters, the ushers, all those little jobs, were all taken over by French. The Algerians, themselves, had nothing but jobs as day laborers, maids, street car conductors, and taxi drivers. Everything else was French. I found that my first few days confirmed my expectations that I was getting into an interesting kind of life. We hadn't been there more than three or four days when we were invited to a big gala. The whole consular corps was going to this theater. I was told to go, get myself a tux and get your wife dressed up. Off we went in a consulate car. The theater was lit up like a Hollywood premier. The Spahis, mounted Algerian troops in colorful uniforms, were there. We got out of the car onto a red carpet which went up into the theater. The theater had sweeping stairways like an opera house. On the way out it was the same way. Your car was called by loudspeaker. Algiers in those days was great for photographs of officialdom and flash bulbs were flashing everywhere. The next weekend or so, the political officer, George Bogardus, who was a red head, called me in and asked if I would go down to a nationalist party meeting at a theater across town and observe what was happening. He couldn't go, he would be too conspicuous. He thought maybe I would be dark enough not to stand out. Thinking of every spy movie I had ever seen, I put on a nondescript suit, didn't shave that day, and hopped on a street car and went down to Bab el Oued, a workers quarter on the other side of the Casbah from the St. George. I was a little early and walked around observing people trying to be as inconspicuous as possible. Finally to use up time, I went to a bar. There was a pinball machine by the window, and I started playing it looking out all the time waiting for the meeting to start. While looking out whom do I see walking by, looking very nondescript, slinking along trying to be inconspicuous, but the British vice consul! My first early experiences sort of bore out the feeling that I was really into something. Q: I can't remember the exact time when the situation turned around, but were you there then? MORIN: No, that was later. I was there during the middle period, a lull. There had been a very bad situation there in Setif in 1945 on VE Day when the French bombed a demonstration that seemed to be getting out of hand and killed anywhere, depending on whom you read, from 10 to 40 thousand people. The Algerians were very quiet in the period I was there, 1948-50. There were two major opposition movements but they were not terrorists but just held meetings. In fact those two movements, later on during the rebellion were considered rather friendly compared to the FLN. But at that time the French were very suspicious of it all, and they were suspicious of us, the US government. They had the idea that we were pushing this. The story in Algiers was that Roosevelt at the summit meeting at the Hotel Anfa in Casablanca had obtained a promise that Algeria would be given to the States. This was completely nonsense, but that is what people thought. The French were most unhappy with the thought that we were sympathetic to the natives and feared we might be doing something for them. For instance, our phones were tapped by our great allies by using equipment left behind by the US Army. I attended Arab movies occasionally, and one day the consul general called a couple of us in and said, "Cut it out. We're getting complaints from the government about you guys showing up in Arab movie theaters." I remember my local secretary was approached...some young fellow made up to her at a dance, and she got to like him. After a time he said, "Look, why don't you tell us what's is going on at the consulate?" She said, "What do you mean?" He said, "Oh, nothing much. Just who does what, what do they talk about and so forth?" She said, "Oh, I wouldn't do that." He got very pushy and proved to be an agent, a deuxième bureau agent. Q: The deuxième bureau is their intelligence. MORIN: So he said, "If you don't cooperate with us, you won't get your passport. We know you have an application to go to Italy on a trip this summer, and you are not going to get it." And she didn't get it either. Q: At the time the French authorities really looked with great suspicion on our consular establishment? MORIN: Oh, yes, very much so. We were blasted in the Paris papers. I remember one period when there were headlines in the French press...the tabloids...saying "the American consulate at Algiers is promoting the nationalist movement." Our political officer got caught in the middle of this. He had asked for permission to talk to one of the opposition leaders. The French government reluctantly gave him permission to go meet with these people, but they almost PNGed [persona non grata] him at the same time.

Description: