Alban Berg and his world PDF

Preview Alban Berg and his world

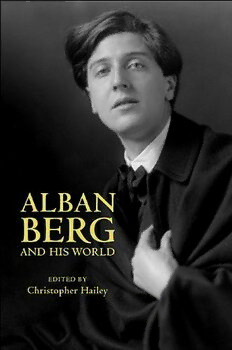

ALBAN BERG AND HIS WORLD This page intentionally left blank ALBAN BERG AND HIS WORLD Edited by Christopher Hailey PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Copyright © 2010 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved For permissions information, see page xv. Library of Congress Control Number 2010925390 ISBN: 978-0-691-14855-7 (cloth) ISBN: 978-0-691-14856-4 (paperback) British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This publication has been produced by the Bard College Publications Office: Ginger Shore, Consultant Christina Clugston, Cover design Natalie Kelly, Design Text edited by Paul De Angelis and Erin Clermont Music typeset by Don Giller This publication has been underwriten in part by a grant from Furthermore: a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund. Printed on acid-free paper. (cid:39) Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Dedicated to the memory of George Perle This page intentionally left blank Contents Preface and Acknowledgments xi Permissions and Credits xv Berg’s Worlds 3 CHRISTOPHER HAILEY Hermann Watznauer’s Biography of Alban Berg 33 TRANSLATED AND ANNOTATED BY NICK CHADWICK A Descriptive Overview of Berg’s Night/Nocturne 91 INTRODUCTION BY REGINA BUSCH TRANSLATED, EDITED, AND WITH COMMENTARY BY CHRISTOPHER HAILEY Berg and the Orchestra 133 ANTONY BEAUMONT “ . . . deinen Wuchs wie Musik”: Portraits, Identities, and 163 the Dynamics of Seeing in Berg’s Operatic Sphere SHERRY D. LEE “Remembrance of things that are to come”: Some Reflections 195 on Berg’s Palindromes DOUGLAS JARMAN 1934, Alban Berg, and the Shadow of Politics: Documents 223 of a Troubled Year INTRODUCTION, TRANSLATIONS, AND COMMENTARY BY MARGARET NOTLEY Alban Berg zum Gedenken: The Berg Memorial Issue of 269 23:A Viennese Music Journal TRANSLATED AND ANNOTATED BY MARK DEVOTO Alban Berg and the Memory of Modernism 299 LEON BOTSTEIN Index 345 Notes on the Contributors 359 • vii • This page intentionally left blank Preface and Acknowledgments Alban Berg has never fit comfortably into the narrative of the “Second Viennese School.” His expressive Romanticism with its nostalgic refer- ences to tonality, his attachment to the preoccupations of fin-de-siècle Vienna, and the sheer sensual appeal of his music have always made him suspect to doctrinaire modernists. Part of the problem, of course, lies in his devotion to Arnold Schoenberg, a figure who created a teleology of musical progress so compelling and domineering that in the searing in- tensity of its glare even Schoenberg’s own works—contradictory and multi-faceted—have been bleached of their historical contingency. As for Schoenberg’s students and followers, who among them is not first and foremost a disciple, even when a renegade? All except Alban Berg—so gracious and accommodating, loyal and devoted, and so very passive in his resistance. He maintains a special place in that narrative because even in its glare he managed to seek and find the shadows. History is texture and texture loves a glancing light. This volume of essays, a companion to the 2010 Bard Music Festival, is an attempt to nudge Berg still further from the flattening perspective of Schoenberg’s radiance by shining just such an angled light upon his music, his charac- ter, and his relationship to some of the broader issues of Viennese and European musical culture. If this carries with it more than a whiff of re- visionism, it is a revisionism whose larger purpose is not to overthrow established figures but to reconnect them to their times. To regard Viennese musical modernism as a saga of harmonic evolu- tion from late-Romantic chromaticism through atonality to serialism is to dismiss nine-tenths of all that this rich musical culture produced. For decades research has been driven by a preoccupation with the conse- quences of the atonal and serial revolutions, a narrative that excluded, by definition, all composers who pursued other paths. This preoccupation encouraged a general cultural bias that also banished them from the con- cert and recorded repertory, published music histories, classroom syllabi, and academic research. In the 1960s and ’70s, a postwar generation of composers, theorists, and historians was growing ever more conscious of the ruptures caused by totalitarian ideologies, the Holocaust, and the Cold War. It was a generation suspicious of dogma and teleology and eager to poke around in the rubble in search of overgrown paths and dis- tant sounds. For them the question of musical syntax was but one of many contested legacies. Their interest in reviving forgotten figures and obscured connections also reflected a gradual transformation of the com- positional landscape in which minimalism, neotonality, and stylistic pluralism were only the most prominent signs of the collapse of the • ix •