Alamein and the Desert War PDF

Preview Alamein and the Desert War

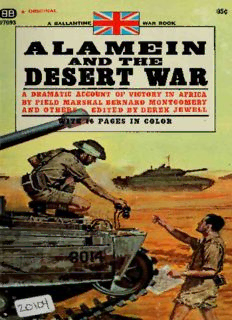

^ ORIGINAL 95( J7093 A BALLANTINE WAR BOOK ALAMEIN AND THE WAB DESERT A DRAMATIC ACCOUNT OF VICTORY IN AFRICA BY FIELD MARSHAL BEBNABD M0NT60MEBY AND OTHEBJK^ EDITED BY DEREK JEWELL ^-M"- f ^i^ *^'"«^' -„,„3I A fyWOLl ^^^ tei. * »d^,J^- __--, -^4^; • Mk 3g l^^^i^wi^^ "The battle which is now about to begin will be one of the decisive battles of history. It will be the turning point of the war." -Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery At Alamein, Montgomery defeated Rommel, the famed "Desert Fox," in one of the most brilliant and savagely fought tank battles of World War II. To commemorate the 25th anniversary of the Battle of Alamein, the London Sunday Times invited Field Marshal Montgomery to return to Africa and recreate the story of his famous victory. To his narrative have been added contributions of world-famed writers and military experts: Len Deighton compares the merits of German and Allied tanks; Barrie Pitt analyzes Rommel's tactics and the fight- ing inTunisia; George Perry interviews German Generals on the African campaign, and other writers complete the picture of desert warfare in this vivid and supremely exciting book specially prepared under the editorship of Derek Jewell. A special 16-page color section shows the uniforms and insignia of the combatants with color photos of Rommel, Montgomery and episodes of the war. ^4 jT 1 jflWJ ^^ ^^'*^*" *^-'-*»^'*'^- " "^'V"J•..f*-"! %/. t^'A i@^ Inj^H&^l^HPr^^^- vl^^l^H I»^^^^K^H^lKw^^to^Ha'f^c^j^n|EmM*, a s.i-.,.v'^VpoiQ S^lii^^.'-w.-.-.' .-^j^ jHp^P^j?^'^^^IHfeifojv^fc^'fn'>^ i^K^^L' *^^K^-*-'^' % ^^f- ' ^^'^kxMir;--^30^B^^M:^^ Alamein andihe war desert edited by Derek Jewell Historical adviser Barrie Pitt Artdirector Michael Rand DesignerDavid Barnes (0) BALLANTINEBOOKS'NEWYORK ^^1 .r life-vs. ^d^^'^ © Times Newspapers Ltd., and Derek Jewell, 1967. First American Printing: July, 1968 Printed in the United States of America BALLANTINE BOOKS, INC. 101 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10003 : : Contents 1 Three years of battles 11 The Benghazi Handicap 1940-1942 by Banie Pitt 24 The patterns ofwar 1940-1943 drawn by Roy Castle 28 The leaders who was who : 32 Rommel's desperate drive by Barrie Pitt 42 Fortress Tobruk a view from the sea by Neil Bruce : 48 Ironmongery ofthe desert by Len Deighton 61 The battle ofAlamein by Field-Marshal Montgomery 95 The chase to Tunisia by Barrie Pitt 2 What makes an army? 100 Rommel and Montgomery photographedby Horst Baumann andIan Yeomans 104 The desert style drawn by Roger Coleman 107 Badges ofbattle drawn by Ken Lewis 109 The Intelligent Bad Element makes good by Philip Norman 120 The Enemy Rommel reassessed 1 : by Hans-AdolfJacobsen andAntony Terry 126 The Enemy 2 what the generals think : by George Perry 130 The private armies by Len Deighton 138 The Gaberdine Swine - and others a glossary ofdesert slang by Peter Sanders 143 Desert newspapers a grassroots press by Susan Raven 147 Lilli Marlene: a song for all armies by Derek Jewell 3 The frmges of conflict 159 Cairo: back from the Blue by Olivia Manning 177 The canvases ofwar by Susan Raven withpaintings by Ardizzone, Gross, Bawden etc. 182 Farouk and the night of shame by Barrie McBride 192 A portrait of Brother Ahmed by Charles Avite drawing by Roger Law 197 The desert poets by Philip Oakes 203 Poems by Keith Douglas, Jocelyn Brooke, Hamish Henderson and Gerald Kersh Introduction: a different kind of war The Desert War fought in Egypt and Libya between 1940 and early 1943 may not have been the most important front in the struggle against Germany, Italy and Japan. But no war could be more fascinating. It was not unimportant, of course. It was crucial for Britain, especially before America'sstrength wasfully geared to help inthe task of beating Hitler. Defeat in the Middle East, and the cutting off of her oil source, could have crumbled Britain's position. The effect on thenation'smoralewould have been catastrophic too, and the few crumbs of victory from the Western Desert gave the British some comfort during the defeat-ridden days of 1941 and 1942. The Soviet Union, engaged on the eastern front in the most terrible and decisive battles of the second world war, would also have been in extreme peril had the Axis been able to use the Nile delta as a springboard to move against Russia's southern borders. But outside the grand strategic context, the Desert War had a A life of its own. particular flavour. It was fought in wide open spaces where there were comparatively few towns and few civilians to get hurt. Ifthere has to be war, then this was the perfect arena. The land is desert but not, on the whole, the soft and yielding sand ofpopular Beau Geste imagination. Beneath the yellow face ofthe Egyptian desert and the greyer surface of the Libyan is rock. It makes, militarily, for good going. This is inhospitable terrain, supporting only scrub, a few tough animals, snakes and lizards, and infuriating myriads of flies. Communicationsweredifficultfor the armies. Water was precious. The sense ofemptiness and loneliness could unhinge a man's mind. There were mirages, discomforts, disappointments. In this cockpit, somehow isolated from the rest of the second world war, a special esprit de guerre grew up. Ifthere can be old- style chivalry in modem war, which some may doubt, then it was here. Itwasquaintlyexpressed inJune 1940,whenthe rafdropped awreath from the air afterthe Italian commander. Marshal Balbo, had been shot down over Tobruk by his own anti-aircraft guns. The heroic, piratical flavour was maintained by Rommel, dashing around among his leading tanks, and by British units like the Long Range Desert Group. Only later, as the desert filled up with larger quantities of men and material, did the modem feeling of two goliaths facing each other intrude. Even then the war produced a hero-figure in Montgomery, as already it had tumed up its O'Con- nors and Gotts and Auchinlecks - and, of course, its Rommel, admired by his enemy like no general since, perhaps, Napoleon. This book, based upon material collected for The Sunday Times Magazine of London in the 25th anniversary year of the Alamein victory, is only the latest in a very long and honourable line of Desert War literature. It is a reporter's book, partly commemor- ative and reminiscent in purpose, partly intended as a reassessment ofcertain aspectsofthewar. It hasalsotried tobesomethingmore. Itconcentrates, aquarterofacentury later, especiallyonthe back- ground to the war, which gave it an extra dimension of interest. For Italy, this war meant the end of a dream of empire. For Britain, too, there were imperialistic overtones. This was in certain respects the latest episode in her long love-hate involvement with the Arabs. That is why sections ofthis book deal with desert slang and its Arabic accretions; with Cairo; with Farouk and the ordinary Egyptians; with the songs, poems, paintings, and news- papers ofthe desert campaigns. Despite all that has been written about this war, there are still new facts, and new perspectives, to be discovered. Against the accepted ideas of its chivalry must be set the fact that wells were sometimes poisoned by retreating troops, which is scarcely chivalrous. Nor is the mine a very chivalrous weapon. There weren't, certainly, many civilians who got hurt. But there were some. Arabs were driven from their land, and the desert-dwellers of Egypt and Libya have suffered grievously in the last quarter- century from the 20 million mines which the British, Germans and Italians left behind in the ground. Since the war, around 30,000 Egyptians have been killed or maimed through stepping on them. The former belligerents have seemed largely unconcerned. It was a war curious in its revelations ofnational behaviour. For in the end, men rather than weapons were decisive. The Italians tried to transform this alien land in their image, instead oflearning to live with it. They built marble monuments. They had the luxury offine sheets, grandiose uniforms, good food and drink, ice cream, even mobile brothels. It was preposterous; a recipe for defeat. The Germans were more realistic. They were good desert soldiers: excellent at fast movement, map-reading and navigation. They had palatable food and fine equipment - from guns and tanks topills, purifiers, powders and goggles. But they loathed thedesert, and it was unkind to them. On the eve of Alamein Rommel was away on sick leave in Germany. His three senior staff officers - Westphal, Gause and Bayerlein - were all ill. Even poor General Stumme, left in charge, had a heart attack and died once Montgomery's assault hadbegun. The British were by contrast, perky as fleas in the desert. The Allied army was one of the Attest in history; bronzed and tough. Maybe this was because the colonising British had had centuriesof experience in tropical medicine. There were British, Australians, New Zealanders, South Africans, Indians, Poles, Czechs, Greeks and French on the Allied side. The British, dressing informally, under an informal discipline, usually wore just boots and shorts (or a weird conglomeration of suede, shaggy sheepskin, corduroy and neckscarves) and lived on tea, bully beefand hard tack. The others all had their talents - the Aussiesinhard, bloody killingmatches; theKiwisinnightfighting; the Indians in guerilla passages. They took to the desert. And, in the end, they triumphed. This book is not encyclopaedic. It deals only with some aspects ofthewar. Neitherdoes itdelve verydeeply into politics. Therehas been enough controversy and no little bitterness already. If there was oncea tendency to blame manyofthe early generals overmuch for their defeats - when indifferent and scanty equipment, too few planes, political manipulations and other factors were often the cause - then the latterday game of scorning the achievements of Alexander and Montgomery has been ludicrously overplayed. Montgomery had a good, experienced army awaiting him. He had Alexander to back him up. He also had excellent equipment, and a lot ofit. But he gave purpose, leadership, self-confldence and logical direction to an army which largely welcomed it. And he won. His fame is as secure as his style, of which he likes not a comma, capital or special spelling changed. Many ofthosewho havewrittenforthisbookoweagreatdebtto literature already published about the war by generals, historians, journalists. It could not have been produced without the assistance ofhundredsofpeople, military and non-military, whoknewthewar at flrst-hand and who have talked or given guidance. They were of many nationalities, and they include the Egyptian authorities, who gave excellent facilities for Field-Marshal Montgomery to return to the Alamein battlefield in May 1967. Its editor, who was not in the Desert War, had the great good fortunetoaccompany Field-MarshalMontgomeryonthatjourney. For the many lessons the Field-Marshal taught me, for his kind- nesses, for the work ofall contributors to this book, I am grateful. Derek Jewell