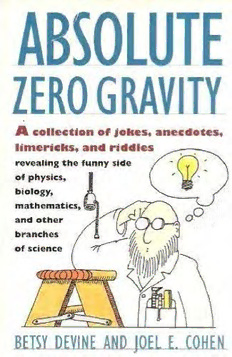

Absolute Zero Gravity: Science Jokes, Quotes, and Anecdotes PDF

Preview Absolute Zero Gravity: Science Jokes, Quotes, and Anecdotes

S J , c i e n c e o k e s Q , u o t e s a n d | A n e c d o t e s by Betsy Devine and Joel E. Cohen p A FIRESIDE BOOK Published by Simon & Schuster New York London Toronto Sydney Tokyo Singapore F ireside Simon & Schuster Building Rockefeller Center 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, New York 10020 Copyright €> 1992 by Betsy Devine and Joel E. Cohen Illustrations Copyright © 1992 by David Goodnight All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Fireside and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc. Designed by Quinn Hall Manufactured in the United Slates of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Devine, Betsy Absolute zero gravity / by joel Cohen and Betsy Devine. p. cm. “A Fireside book.” 1. Science~—Humor. I. Cohen, joel E. II. Title. Q167.C65 1992 502'.07—dc20 92-21962 CIP ISBN: 0-671-74060-1 The authors would like to make grateful acknowledgment for the use of the following published material: Light Bulb Jokes (throughout) excerpted from the Canonical Collection of Light Bulb Jokes, copyright © 1988 Kurt Guntheroth. Used with permission of Kurt Guntheroih. Lee DuBridge and Lord Kelvin quotes (p. 99), Sam Goldwyn quote (p. 144)- From .4 Stress Analysis of a Strapless Evening Gown, Robert A. Baker (editor), Anchor Books, Doubleday and Co.» 1963. Reprinted by permission of the publisher: Prentice-Hall/A Division of Simon & Schuster, Englewood Cliffs, New jersey. Darwin quotes (pp. 32, 67, 134). From Charles Darwin and the Voyage of the Beagle, Charles Robert Darwin, edited and with an introduction by Nora Barlow, Philosophical Library, 1946. T. H. Huxley anecdotes {pp. 74* 75, 100). From T. H. Huxley: Scientist, Humanist, & Educator, by Cyril Bibby, C. W. Watts & Co., Ltd. 1959. Linnaeus anecdotes (pp. 77—8)- From The Compleat Naturalist: A Life of Linnaeus, Wilfred Blunt (with the assistance of William T. Steam), Viking Press, 1971- Mathematical greeting cards* bumper stickers, tombstones, light bulb joke table (pp. 37-8, 40, 42). Reprinted with permission from SIAM News: Volume 18, Number 5; Volume 19, Number 1; Volume 2i» Number 6; Volume 22, Number 5; Volume 24, Number 3. “The Fifth Quadrant” competitions are edited by Richard Bronson and Gilbert Steiner. permissions continued at back of book. T C able of on ten ts Ack nowledgments 6 Preface by Joel E. Cohen 7 Introductory Joke 9 Academia 10 The Scientific Personality 13 22 Scientific Specializations Interdisciplinary Studies 47 Love, Sex, Marriage, and Scientists 56 Tales of the Great Scientists 64 Teaching Science 86 Scientific Reputations 99 Scientific Writing on the Walls 108 10 Medical Science 1 Publish or Perish 120 Scientific Product Warning Labels 123 Experimental Apparatus 125 The International Scientific Community 130 Women in Science 134 Food for Thought 137 Popular Science 14 1 Scientists in Heaven and Hell 14 5 Scientific Aphorisms 149 Logical Conclusions 151 Afterglow 155 Acknowledgments thanks io: Bob Langlands Michael Larsen Fred Almgren Leon Lederman Phil Anderson Joe Lehner William Anderson David Leston Cathy Andruiis Gerri Lindner Peter Astor Robert J. Lipshutz Krishna S. Athreya Saunders MacLane John Biggs Gwendolyn Markus Enrico Bombieri Lawrence Markus Gaby Borel George Masniek Richard Bronson Frank McCullough Ray Brown Sharon Johanson McCullough R. Eugene Burke E. j. McShane Hal Caswell Louise Morse Dev Chen Dan Mostow David J. Cohen Chiara Nappi Sidney Coleman Paul Nyiri Paul Cranefield Ingram Olkin David Damrosch Abraham Pais Bob Dempsey Robert Parks Murray Devine Jonathan Pi la Kevin Devine Robert Poilak James Ebert Peter Ross Paul Feit Mary Beth Ruskai Benji Fisher Amy Schoener Shelley Glashow Daniel Seiver Paul Goldberg A1 Shapere Murph Goldberger Ruby Sherr William T. Golden Gus Simmons Herman Goldstine Montgomery Slatkin Anne Gonnella Gilbert Steiner Madelyn T. Gould Edward Subitskv Claire Thomson Graaf Earl Taft Raymond Greenwell Alvin Thaler Victor Gribov Joan Treiman Kurt Guntheroth Sam Treiman Israel Halperin Marvin Tretkoff Susan Hewitt Albert W, Tucker Charles Issawi Paul Vojta Nina Issawi David Vondersmith John Van Iwaarden Edward Walters Jay Jorgenson Andre Weil Steve Just David Wendroff Mark Kac Edward White Nick Khuri Ludmila Wighiman Liz Khuri Mira Wilczek Larry Knop Amity Wilczek Joe Kohn Frank Wilczek Manny Krasner Dick Wood Peter Kronheimer C. N. Yang Sevda Kursunoglu Peter Yodzis T. Kuster Aki Yukie P reface When I was a freshman in college, I showed my calculus teacher a formula beloved by every high school scientist: jV = (In case you can’t read, this says: sex = fun. It’s a freshman’s idea of titiliation.) He frowned. Then he said: “Doesn’t the left side need a dx?” As I picked up ray equation and left, I thought: “What a jerk! He thinks it’s mathematics!” Thirty years later, I wondered whether I had been had. Maybe my section man saw that the equation said sex — fun. Maybe he was pretending to take it seriously. If so, I swallowed his act. Scientists are funny people. Not just the great ones who think they’ve discovered the secret of life or of the brain or of the common cold. Even ordinary day-to-day scientists are funny, because they all think that the world makes sense\ Most people know better. In pursuit of their delusion, scientists have developed some pretty strange habits of thought and behavior. They constantly act as if things have explanations. This article of faith is very weakly supported by day-to-day experience. To justify this credo, scientists ignore all the things that don’t have explanations (take your choice). They ex pend no end of the taxpayer’s money to isolate, build walls around, and study intensely the few crumbs of life that do have explanations. Scientists also insist that other people have to be able to under stand their explanations. Scientists are forever explaining things to each other. They publish thousands of scientific journals with hun- dreds of thousands of articles, each read by two of the authors’ friends and three of their enemies and an occasional, mad graduate student. They swarm, like bees in search of a nesting site, from one scientific meeting to another, shifting restlessly from one lecture to another, from a transparency with numbers too small to read to equations with notation too complex to comprehend—explaining and trying to grasp explanations. Scientists are just as good at explaining things convinc ingly as the director of the CIA, the chairman of the KGB, the pres P reface 8 ident of any tobacco company, certain religious leaders, and other revered figures of public and private life. The reason that scientific explanations sound so strange is that they are. Let me explain. Daily life is a jumble. (You noticed that, too?) Therefore the parts of experience that make sense and have explanations don’t have a lot to do with daily life. So scientists invent new language—new words, new conventions about words, plus new symbols and conventions about symbols—to describe the rare parts of life that make sense. (To be a properly formed mathematical expres sion, Jex needs a dx, my calculus teacher told me, as if I didn’t know.) When it comes to explaining these esoteric descriptions, strange con cepts are invented, exploited, enshrined, and discarded. Most of these concepts would never be entertained seriously by any practical person with her or his feet on the ground. (Phlogiston, the ether, and phrenology are merely the whipping boys of retrospective wisdom, it’s a safe bet that 80 percent of today’s explanatory concepts—mind you, not the ones I’ve proposed, but maybe some of yours, and certainly most of his—will seem absurd in fifty years, if anyone then can even remember them.) Like firework rockets launched at night, scientific concepts streak out of nowhere, glitter, and are gone. They are useful for all that, because they lift scientists’ attention skyward and feed their hopes. Because this is a book of humor and anecdotes about science and scientists (in addition to a considerable number of jokes we just happened to like), there are lots of stories about the work of making sense of the world, about explanations and the people who give them (sometimes known as teachers), and about the wild language and weird concepts of scientific explanations. But one thing we do not dare to tell jokes about: science is serious. No joke. If my colleagues ever see this book, do you know what they’ll say? “It’s his greatest contribution to science,” and the career of one working scientist goes in the trash, (it’s okay for Betsy to write a scientific joke book; after all, she’s a writer and a historian.) No, sir! You cannot take time out from making measurements and calculations and theorems and hypotheses to tell jokes about the seriousness of science. If you tell jokes, maybe all those people who aren’t so sure that the world makes sense might be on to something. So please, folks, buy this book, read it, and enjoy it. But don’t show it to my colleagues. Joel E. Cohen I J ntroductory oke A young scientist whose boyfriend was an aspiring comedian went with him to the jokewriters’ annual convention, expecting to hear some fantastic stories. Instead, the featured comic began to rattle off a series of numbers. “Ninety-three!” said the speaker, and the audience chuckled ap preciatively. “Two hundred twelve!” They laughed again. “One thou sand thirty-seven!” More laughter. The scientist couldn’t stand it any longer. She nudged her friend and whispered, “What’s going on?” “Simple,” he said. “You see, every joke in the world has been catalogued and given a number. When one of us says ‘Ninety-three,’ that means joke number ninety-three. So we laugh. Get it?” “You mean,” asked the scientist dubiously, “you’re going to crack up if I say to you, ‘Twenty-six’?” “No, no,” said the boyfriend, “your delivery is wrong. Listen to this guy. He’s good and you might learn something.” So the scientist tried to appreciate the comedian’s technique on forty-six, nine hundred eighty-nine, and two thousand five hundred thirty-six. Then the comedian paused dramatically, waving his hands for silence. When he had the audience’s full attention, he shouted “Ten thousand—two hundred—and three!” There was pandemonium. People clapped and cheered. The scientist’s boyfriend was laughing so hard that tears ran down his face and he could hardly stand. “What happened? What happened?” she demanded. “Why was that one so funny?” “Well,” said her friend, “we never heard that joke before!” A cad em ia TO BE FAIR, WE ADMIT THAT MOST OF THEM CAN SPELL THEIR JOB TITLES In any academic setting, the scientists get along like a great big happy family'—with lots of bickering. Engineers tell physicist jokes, physicists tell mathematician jokes, mathematicians tell engineer jokes, and it all goes around and around. But one thing all the scientists agree on is telling dean jokes. Like, did you hear about the dean who was so confused that the other deans noticed? Or how about this one: Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, an intel ligent dean, and a stupid dean were locked in an office with no key. Which one discovered a clever way for them all to get out? Believe it or not, it was the stupid dean—because Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, and an intelligent dean do not exist. THE DEAN OF ACADEMIC LIGHT BULB JOKES How many deans does it take to change a light bulb? Two. One to assure the faculty that everything possible is being done, while the other screws the bulb into a faucet. JUST A FEW MORE ITERATIONS AND SOMEBODY WILL HIRE A DEAN Andre Weil’s Law of Faculties: First-rate people hire other first- rate people. Second-rate people hire third-rate people. Third-rate people hire fifth-rate people.