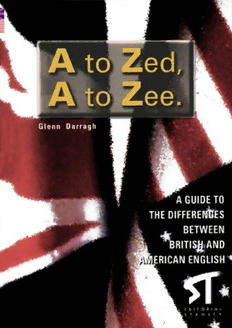

Table Of ContentA TO ZED, A TO ZEE

A GUIDE TO THE DIFFERENCES

BETWEEN

BRITISH AND AMERICAN ENGLISH

A TO ZED, A TO ZEE

A GUIDE TO THE DIFFERENCES

BETWEEN BRITISH AND AMERICAN ENGLISH

WRITTEN BY

GLENN DARRAGH

PUBLISHED BY

EDITORIAL STANLEY

LAYOUT

ANGELA GOMEZ MARTIN

FRONT PAGE DESIGN

DISENO IRUNES

© EDITORIAL STANLEY

APDO. 207 - 20302 IRUN - SPAIN

TELF. (943) 64 04 12 - FAX. (943) 64 38 63

ISBN: 84-7873-346-9

DEP. LEG. BI-930-00

FIRST EDITION 2000

PRINTERS

IMPRENTA BEREKINTZA

Contents

Preface

Introduction: Why are they so different? v

Part one: Spelling 2

Part two: Pronunciation 11

Part three: Grammar and Usage 19

Part four: A to Zed: a GB / US lexis 27

Part five: A to Zee: a US / GB lexis 75

Further Reading 121

Preface

This book is intended for Americans and This state of affairs is reflected in the

Britons who want to understand each structure and content of the present

other better, and for foreign students of book, which makes no pretence (or

either American or British English who pretense) of being exhaustive, but which

want to familiarise (or familiarize) does try to be comprehensive. Short

themselves with the other main variety initial chapters outline the historical

of the language. According to George background and the differences in

Bernard Shaw, the United States and pronunciation, spelling and grammar.

England are two great nations separated The main part of the book, however,

by a common tongue. In fact, most of consists of a dictionary of British

the time the two peoples understand vocabulary and cultural references which

each other fairly well, or think they do. someone from the United States might

The accent is different, of course, but it have trouble understanding, and of a

presents no more of a barrier than any dictionary of American vocabulary and

regional accent would. Differences in cultural references that might present

grammar, syntax and spelling are problems to someone from the British

relatively minor. The main differences, Isles. As the book is not aimed at

and they are huge, are lexical and academics, but at laymen (or

cultural. laypersons) who are curious about

language, phonetic differences are

shown, when necessary, by a figured

pronunciation. The A to Zed section is

written to be read by Americans, the/4

to Zee section by Britons. Finally, a

number of older terms have been

retained in both sections of the

dictionary for the benefit of the small

number of Americans and Britons who

happen to be complete novices in the

study of English as a foreign language.

Introduction: Why are they so different?

When a Briton and an American meet, of the south-eastern part of England,

even though they are far from mutually which is where, in the early 17th century,

unintelligible, each is soon aware of the first British colonists originated.

differences in the speech of the other. Their peculiar treatment of the final r

First, the accent is different: survives in New England and the South,

pronunciation, tempo, intonation are but it is exceptional in the US as a

distinctive. Next, differences in whole. The distinctive American r, a kind

vocabulary, idiom and syntax occur, as of muffled growl produced near the back

they would in a foreign language: of the mouth, is fully sounded. It is very

individual words are misunderstood or similar to the r still pronounced in parts

not understood at all, metaphorical of the west and north of England, and in

expressions sound bizarre, subtle Scotland and Ireland, and was almost

irregularities become apparent in the certainly brought to America by

way words are arranged, or in the subsequent colonists from those parts.

position of words in a sentence, or in Since most of the British settlement in

the addition or omission of words. It is North America in the 19th century came

estimated that some 4,000 words and from the north and west of England and

expressions in common use in Britain from Ireland, especially from the

today either do not exist or are used northern counties of Ulster, rhotic

differently in the US. These differences speech, as it is called, eventually spread

are reflected in the way British and across the continent. In many other little

American English are written, so that ways, standard American English is

variations in spelling and punctuation reminiscent of an older period of the

also emerge. Finally, there are immense language. For example, Americans

cultural divergences, ranging from pronounce either and neither-with the

different trademarks for everyday vowel of teeth or beneath, while in

products to different institutions and England these words have changed their

forms of government. Little wonder, pronunciation since the American

then, that even in this age of global colonies were founded and are now

communications, we are still able to pronounced with an initial diphthong,

misunderstand each other. Before like the words eye and nigh. (For a

examining each of these major fuller discussion of these and other

dissimilarities in detail, it may be useful pronunciation differences, see Part 2.)

to consider how they have arisen.

It is said that all emigrant languages are

In fact, many of the distinctive phonetic linguistically nostalgic, preserving

features of modern American English archaic pronunciations and meanings.

can be traced back to the British Isles. The word vest provides an interesting

To take a single example, the r at the example of one of the ways in which the

end of words is pronounced in markedly vocabularies of Britain and America

different ways in the 'standard' varieties were to grow apart. The first recorded

of American and British English. In the use of the word occurs in 1666 (in the

'received pronunciation' of GB, it is diary of Samuel Pepys), referring to 'a

barely sounded at all, so that words like sleeveless jacket worn under an outer

there and water are pronounced theah coat'. The direct descendant of this

and watuh. This pattern is characteristic usage is the modern American vest,

A TO ZED, A TO ZEE STANLEY v

meaning waistcoat. In the intervening spelling bee. low-down, to have an ax

centuries, however, the meaning of the to grind, to sit on the fence, to saw

word has shifted in Britain, so that it wood, and so on. At the same time,

now applies to 'a piece of clothing worn other words were being assimilated

on the top half of the body underneath a ready-made into the language from the

shirt'. Americans have retained a different cultures the settlers came into

number of old uses like this or old words contact with. Borrowings from the

which have died out in England. Their Indians include pecan, squash,

use of gotten in place of got as the past chipmunk, raccoon, skunk, and

participle of get was the usual form in moccasin', from the French, gopher,

England two centuries ago; in modern pumpkin, prairie, rapids, shanty, dime,

British English it survives only in the apache, brave and depot; from the

expression ill-gotten gains. American Spanish, alfalfa, marijuana, cockroach,

still use mad as Shakespeare did, in the coyote, lasso, taco, patio, cafeteria and

sense of angry ('Don't get mad, get desperado; from the Dutch, cookie,

even.'), and have retained old words like waffle, boss, yankee, dumb (meaning

turnpike, meaning a toll road, and fall as stupid), and spook. Massive immigration

the natural word for the season. The in the 19th century brought new words

American I guess is as old as Chaucer from German (delicatessen, pretzel,

and was still current in English speech in hamburger, lager, check, bummer,

the 17th century. The importance of such docent, nix], from Italian [pizza,

divergences was compounded by two spaghetti, espresso, parmesan,

parallel processes. Some words which zucchini] and from other languages.

the pilgrims and subsequent settlers Jews from Central Europe introduced

brought to the New World did not many Yiddish expressions with a wide

transplant, but in England they survived: currency in modern America: chutzpah,

e.g. fortnight, porridge, heath, moor, kibitz, klutz, schlep, schmaltz, schlock,

ironmonger. Far more important, schnoz, and tush. Likewise, many

however, was the process by which, Africanisms were introduced by the

under the pressure of a radically enforced immigration of black slaves:

different environment, the colonists gumbo, jazz, okra, chigger. Even

introduced innovations, coining new supposedly modern expressions like

words and borrowing from other cultures. with-it, do your thing, and bad-mouth

are word-for-word translations of

Many living things, for example, were phrases used in West African languages.

peculiar to their new environment, and Eventually many of these enrichments

terms were required to describe them: would cross the Atlantic back to

mud hen, garter snake, bullfrog, potato England, but by no means all of them.

bug, groundhog. Other words illustrate Those that did not cross back form the

things associated with the new mode of basis of the differentiation that has

life: back country, backwoodsman, taken place between the American and

squatter, clapboard, corncrib, bobsled. the British vocabulary (Parts 4 and 5, for

This kind of inventiveness, dictated by an examination of current lexical

necessity, has of course continued to differences and explanations of many of

the present day, but many of the most the terms cited above).

distinctive Americanisms were in fact

formed early: sidewalk, lightning rod, A further important change was to take

vi STANLEY A TO ZED, A TO ZEE

place, in the domain of spelling. In the surprisingly few major differences. On

years immediately following the the whole, however, Americans, as

American Revolution, many Americans though impelled by an urgent need to

sought to declare their linguistic as they express themselves, appear less

had their political independence. In constrained by the rules of grammatical

1780, John Adams, a future president of form. For instance, they tend to bulldoze

the United States, proposed the their way across distinctions between

founding of an 'American Academy for the various parts of speech. New nouns

refining, improving, and ascertaining the are compounded from verbs and

English Language'. The plan came to prepositions: fallout, blowout, workout,

nothing but it is significant as an cookout, the runaround, a stop-over, a

indication of the importance Americans try-out. Nouns are used as verbs - to

were beginning to attach to their author, to fund, to host, to alibi (an

language. The more ardent patriots were early example of the practice was to

demanding the creation of a distinctly scalp] - and verbs are used just as

American civilization, free of the casually as nouns: an assist, a morph.

influence of the mother country. Defence Any number of new verbs can be

of this attitude was the life-work of created by adding the suffix -ize to a

Noah Webster (1758 - 1843), author of noun or to the root of an adjective:

The American Spelling Book, first standardize, fetishize, sanitize,

published in 1783 and destined to sell prioritize, diabolize. If the exuberance

an estimated 80,000,000 copies over of American English is reminiscent of

the next hundred years. This work, from anything, it is of the linguistic energy of

which countless immigrants learnt their the Elizabethans. In the early part of the

English, introduced such typical 20th century, H.L. Mencken was already

spellings as honor, color, traveler, making the point. American English, he

defense, offense, center, theater, ax, said, 'still shows all the characteristics

plow, and jail. The influence of that marked the common tongue in the

Webster's American Spelling Book and days of Elizabeth I, and it continues to

of his later American Dictionary of the resist stoutly the policing that ironed out

English Language (1828) was Standard English in the seventeenth and

enormous. It is true to say that the eighteenth centuries'.

majority of distinctively American

spellings are due to his advocacy of the The present geopolitical, technological,

principles underlying them. (The main financial and commercial supremacy of

differences are outlined in Part 1.) the United States unquestionably

Moreover, some of the characteristics of underlies the expansiveness and spread

American pronunciation must also be of its language, nowhere more so than

attributed to Webster, especially its on the level of colloquial or popular

relative homogeneity across so vast a speech. Occasionally words in British

continent and its tendency to give fuller English become fashionable enough to

value to the unaccented syllables of cross the Atlantic, but the vast majority

words (see Part 2). of words - like the vast majority of

films, television programmes, best

As regards the basic grammar and sellers, news magazines, and pop music

structure of the language, there are lyrics which convey them - no longer

A TO ZED, A TO ZEE STANLEY vii

travel westwards, but eastwards. This

situation is not without irony. In the

1780s, some patriots were proposing

that English be scrapped altogether as

the national language and replaced by

another: French, Hebrew and Greek

were candidates. The last of these was

rejected on the grounds that 'it would

be more convenient for us to keep the

language as it was, and make the

English speak Greek'. Two hundred and

some years later, it seems fairly obvious

that the Americans will keep and

develop their variety of English just as

they please, and the British will have to

adapt as best they can. It is a process

that is already well under way, with

thousands of words and expressions

that were exclusively American a few

years ago now part of the written and

spoken language in both its varieties.

But there is no reason to deplore this

fact. It is simply a sign that the language

is doing what it has always done: it is

changing and revitalizing itself.

Viii • STANLEY A TO ZED, A TO ZEE

P A RT O NE

Spelling 2

1. The color/colour group 3

2. The center / centre group 3

3. The realize / realise group 4

4. The edema / oedema group 5

5. The fulfill / fulfil group 6

6. One letter differences 7

7. Miscellaneous 8

P A RT T WO

Pronunciation 9

1. Pronunciation of 'r' 9

2. Pronunciation of 'a' 10

3. Pronunciation of 'o' 10

4. Pronunciation of 'u' 11

5. Pronunciation of 't' 11

6. Pronunciation of particular words 12

7. Stress and articulation 14

P A RT TTHHRREEEE

Grammar and Usage 15

1. Irregular verbs 16

2. Use of Past Simple

and Present Perfect tenses 17

3. Auxiliary and modal verbs 18

4. Expressions with 'have' and 'take' 19

5. Position of adverbs 19

6. Use of 'real' as an intensifier 19

7. Collective nouns 20

8. Prepositions 20

9. Use of 'one' 21

10. Other usages 22