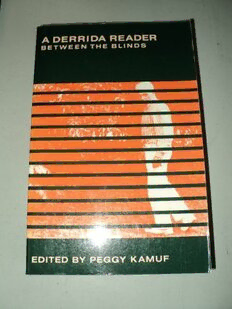

Table Of ContentA DERRIDA READER

BETWEEN THE BLINDS

Edited,

with an introduction and notes,

by Peggy Kamuf

Columbia University Press New York

Copyright acknowledgments continue

at the back of the book.

.) ;

Columbia University Press

New York Oxford

Copyright © 1991 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

ca~oein\-in-Publication

Library of Congress Data

Derrida, Tacques.

[Selections. English. 1991j

A Derrida reader : between the blinds I edited by Peggy Kamuf.

p. cm.

"With only one exception, all the excerpted translations

have been previously published" - Pref.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-231-06658-9 (cloth).-ISBN 0-231-06659-7 (paper)

r. Philosophy. 2. Deconstruction.

I. Kamuf, Peggy, 1947- . II. Title.

B2430.D481D4713 1991

194-dc20

90-41354

CIP

Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are Smyth-sewn

and printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper

Book design by Tennifer Dossin

Printed in the United States of America

C IO 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 I

Contents

Preface vii

Introduction: Reading Between the Blinds xiii

Part One: Differance at the Origin 3

r. From Speech and Phenomena 6

2. From Of Grammatology 31

3. From "Differance" 59

4. "Signature Event Context" Bo

5. From "Plato's Pharmacy" II2

Part Two: Beside Philosophy-"Literature" 143

6. "Tympan" 146

7. From "The Double Session" 172

8. From "Psyche: Inventions of the Other" 200

9. "Che cos'e la poesia?" 22!

Part Three: More Than One Language 241

ro. From "Des Tours de Babel"

r r. From "Living On: Border Lines"

12. "Letter to a Japanese Friend"

13. From "Restitutions of the Truth in Pointing"

vi Contents

Part Four: Sexual Difference in Philosophy 313

14. From Glas 31 s

15. From Spurs: Nietzsche's Styles 353

16. "Geschlecht: Sexual Difference, Ontological Difference" 378

17. From "At This Very Moment in This Work Here I Am" 403

18. From "Choreographies"

Part Five: Tele-Types (Yes, Yes) 459

19. From "Le Facteur de la verite" 463

20. From "Envois" 484

21. From "To Speculate-on 'Freud' 11 516

22. From "Ulysses Gramophone: Hear Say Yes in Joyce" 569

Bibliography of Works by Jacques Derrida 601

Selected Works on Jacques Derrida and Deconstruction 613

Index of Works by Jacques Derrida 617

Index 619

Preface

In 1962, Jacques Derrida published a long critical introduction to his

translation of Husserl's The Origin of Geometry. With that work he

began what has proved to be one of the most stunning adventures of

modem thought. It promised, from its first public acts, an explana

tion with philosophical traditions unlike any other. That promise

has since been realized in more than twenty-two books and count

less other uncollected essays, prefaces, interviews, and public inter

ventions of various sorts. Many of these have been translated, inte

grally or in part, into English. And new texts are appearing regularly,

as Derrida continues to write and to teach, in Europe and North

America and indeed throughout the world.

Today, it is with the word deconstruction that many first associ

ate Derrida's name. This word has had a remarkable career. Having

first appeared in several texts that Derrida published in the mid-

196os, it soon became the preferred designator for the distinct ap

proach and concerns that set his thinking apart. Derrida has con

fessed on several occasions that he has been somewhat surprised by

the way this word came to be singled out, since he had initially

proposed it in a chain with other words-for example, differance,

spacing, trace-none of which can command the series or function

as a master word.

No doubt the success of deconstruction as a term can be explained

in part by its resonance with structure which was then, in the 1960s,

the reigning word of structuralism. Any history of how the word

deconstruction entered a certain North American vocabulary, for

instance, would have to underscore its critical use in the first text

by Derrida to be translated in the United States, "Structure, Sign,

viii Preface

and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences." This was the

text of a lecture delivered at Johns Hopkins University in 1966. In

that lecture, he considered the structuralism of ethnologist Claude

Levi-Strauss whose thought, as Derrida remarked, was then exerting

a strong influence on the conjuncture of contemporary theoretical

activities. The word de-construction occurs in the following passage

concerned with the inevitable, even necessary ethnocentrism of any

science formed according to the concepts of the European scientific

tradition. And yet, Derrida insists, there are different ways of giving

in to this necessity:

But if no one can escape this necessity, and if no one is there

fore responsible for giving in to it, however little he may do so,

this does not mean that all the ways of giving in to it are of

equal pertinence. The quality and fecundity of a discourse are

perhaps measured by the critical rigor with which this relation

to the history of metaphysics and to inherited concepts is

thought. Here it is a question both of a critical relation to the

language of the social sciences and a critical responsibility of

the discourse itself. It is a question of explicitly and systemati

cally posing the problem of the status of a discourse which

borrows from a heritage the resources necessary for the de

construction of that heritage itself. A problem of economy and

strategy.*

As used here, "de-construction" marks a distance (the space of a

hyphen, later dropped! from the structuring or construction of dis

courses, such as Levi-Strauss', that have uncritically taken over the

legacy of Western metaphysics. If, however, it cannot be a matter of

refusing this legacy-"no one can escape from it"-then the dis

tance or difference in question is in the manner of assuming respon

sibility for what cannot be avoided. Deconstruction is one name

Derrida has given to this responsibility. It is not a refusal or a

destruction of the terms of the legacy, but occurs through a re

marking and redeployment of these very terms, that is, the concepts

of philosophy. And this raises the problem, as Derrida puts it, ltof

the status of a discourse which borrows from a heritage the resources

necessary for the de-construction of that heritage itself." It is in the

critical space of this problem, which needs to be thought through

rigorously, systematically, and responsibly, that Derrida proposes to

situate his discourse.

•Writing and Difference [1967], p. 289. All quotations of Derrida's works are from

published translations where available. For complete reference, consult the bibliography at

the end of this volume by the date given in brackets (e.g., here 1967!.

Preface ix

Since its introduction, the work of Jacques Derrida has traced

wide and diverse paths of influence both within and without the

academic disciplines, wherever the relation to the heritage of West

ern thought has become critical. Although this influence may have

been felt first among literary theorists, it quickly overran the bound

aries of literary studies or of any academic discipline. Theologians,

architects, film makers and critics, painters, legal scholars, musi

cians, dramatists, psychoanalysts, feminists, and other political and

social theorists have all found indispensable support for their reflec

tion and practice in Derrida's writing. Even philosophy in America,

which began trying to purge itself of continental influences more

than a century ago, has had to yield significant ground to Derrida's

insistent questioning of the philosophical discipline. Thus, although

one can still hear or read statements to the effect that Derridean

deconstruction is the affair of a few North American literary critics,

the odds are good that they are coming from a philosopher who is

trying to ignore the obvious of what is going on all around him or

her.

Such discursive tactics of containment or denegation have flour

ished in the vicinity of deconstruction, and not only among philoso

phers. Both academic journals and the popular press have now and

then bristled with indignation when confronted with the evidence

that deconstruction is taking hold in the North American cultural

landscape. But this is understandable; Derrida's work is disconcert

ing and deliberately so. The present collection of essays and extracts

will not conceal that fact. A reader who wants to approach this

writing is therefore urged to proceed patiently, as well as carefully.

Be advised that the most familiar may well begin to appear strangely

different. As Derrida writes in one of the extracts from Of Gramma

tology included here, his final intention is "to make enigmatic what

one thinks one understands by the words 'proximity,' 'immediacy,'

'presence'," that is, the very words with which we designate what is

closest to us.

As to the choice and arrangement of texts, I have followed several

principles and endeavored to make them compatible with each other.

The easiest and most conventional of these is a very roughly chro

nological ordering that can serve to illustrate some of the ways

Derrida has reshaped his thought over the last twenty or so years.

Between the earliest texts included here (extracts from Speech and

Phenomena and Of Grammatology) and the most recent ones, how

ever, there is also an undeniable constancy and coherence which

belie any superficial impression that Derrida has revised or moved

x Preface

away from some former or initial way of thinking. Indeed, one of the

more extraordinary things about Derrida's thought is the way it has

shaped itself along a double axis or according to a double exigency:

it seems always to be moving beyond itself and yet nothing is left

behind. The first writings remaining implied in the succeeding ones,

they are literally folded into different shapes and yet do not lose

their own particular shape in the process. Nevertheless, because the

work advances by bringing its past along, it is necessary up to a point

to respect its chronology.

No sooner, however, has one underscored the coherence of these

writings than one must acknowledge as well their remarkable diver

sity in subject, theme, form, tone, procedure, occasion, and so on.

Here a second principle is called for, one that does not present itself

so easily. The solution I have come to for grouping texts is, needless

to say, only one of the many that could have been chosen to repre

sent this diversity. As the reader will soon see, I have applied in

effect no single principle but have grouped the sets of selections

according each time to a different, loosely defined criterion. Numer

ous other criteria suggested themselves as did so many other texts

that had to be left out. What is more, almost all of the texts included

here would fit in several of the categories. This is but one of many

possible Derrida "readers."

As to why there are so many extracts and so few complete essays,

I decided, rightly or wrongly, that only this method permitted a

tolerable, though still insufficient representation of the diversity and

continuity of Derrida's work. I admit, however, that I hesitated long

before adopting this procedure. Derrida's writings are intricately

structured and perform a delicate balancing act between recalling

where they have been and forewarning where they are going. The

majority of them are deployed around extensive quotation of other

works and they elaborate complex patterns of renvois, Most often

the texts juxtapose and counter one style or tone with another,

shifting, for example, between the strictest form of philosophical

commentary and writing of a sort that such commentary has always

by definition, excluded. Needless to say, much of this intricacy,

balance, and counterplay has been sacrificed by the technique of

cutting out excerpts of the texts. On the one hand, I have consoled

myself for this loss with the thought that, with few exceptions, all

of the works excerpted here are readily available in extenso, and thus

no reader of A Derrida Reader need be content with shortened ver

sions (see the appended bibliography which also lists some sugges

tions for secondary reading). I made a mental note to remind readers

Preface xi

of this fact which is what I am doing now. On the other hand, I

garnered a certain courage to excerpt so ruthlessly from Derrida's

own repeated insistence on the partialness of any text, a partialness

that is not recuperable in some eventual whole or totality. Moreover,

the notions of cutting, grafting, piecing together-extracting-are

everywhere in evidence in Derrida's texts, both as themes and as

practices, until they are virtually coextensive with the text he is

always interrogating and performing. Indeed, the masterful work

Glas may be read as a long reflection on cutting, which is always

culpable, put into practice. This is one reason I have placed a series

of brief passages from that work in the spaces between the sections.

These may be thought of as blinds or jalousies lowered into place as

reminders: "Look at the holes, if you can"; read between the blinds.

Ultimately, however, there is no final justification of this cutting

and splicing. A desire was always obscurely in play (and desire is the

very order of the unjustifiable) to offer up for another reading texts

that I have returned to more than once out of love and respect, but

also probably out of an unfathomable puzzlement. No doubt it is the

utterly naive desire that, by presenting these texts to be read again, I

will get back some signs of my own understanding.

And that leads me to a final principle-or rather, less a principle

than a wish that accompanied the editing of these pages. It is that

this volume should engage each of its readers differently even as it

made certain texts available to a broader general comprehension. I

wanted it to be possible, in other words, for every reader to encoun

ter both the same and a different book as all other readers, and for

the same prepared trajectory to be nevertheless each time singular

and unpredictable. How to reconcile these two aims? No answer

presented itself in simple terms; instead, a reflection on that ques

tion resulted in the essay "Reading Between the Blinds" which is

given here in the guise of an introduction to the selected excerpts

and essays. It may be read as the record of a negotiation, or exposi

tion, between two versions of A Derrida Reader.

With only one exception, all the excerpted translations have been

previously published and are reproduced here most often with only

minor changes, if any. It should be said that Derrida's writing ac

tively resists translation by seeking out the most idiomatic points in

the language, by reactivating lost meanings, by accumulating as far

as possible the resources of undecidability which lie dormant in

syntax, morphology, and semantics. The result can often seem ob

scure to whoever has been taught that a standard of so-called clarity

xii Preface

of style is the first and indispensable criterion of expository prose.

But Derrida never cultivates this "obscurity" for its own sake; on

the contrary, the apparent density of his writing has its correlative

in a relentless demand for clarity of another order, which may be

called, in a seeming paradox, a clarity about the obscurity, opacity,

and fundamental difference of language. Standard notions of clarity

or "correct" style, when viewed from this perspective, must be seen

as, themselves, obscurantist since they encourage a belief in the

transparency of words to thoughts, and thus a "knowledge" con

structed on this illusion. Deconstructing this knowledge will neces

sarily be a matter of some difficulty.