Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War PDF

Preview Zinky Boys: Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War

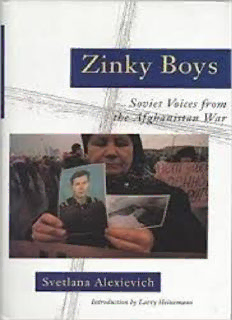

Zinky Boys : Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War Svetlana Alexievich Introduction by Larry Heinemann Praise for the British edition of Zinky “This book, a brilliant series of interviews with teenage conscripts, gives a wonderful, understanding account of the mixture of idealism, heroism, and horror that made up this most disastrous of all Russian wars.” — The Guardian “The question of how to honour the dead and respect the memories of boy veterans plunged into an unjust war has seldom been more honestly and objectively recorded?’ —Daily Mail “Zinky Boys does raise, in stark fashion, the problem which has plagued Americans for twenty years: how to honour the dead and respect the rights of the veterans of a war which has become widely accepted as a national historical disgrace?’ —Literary Review “Through these brief statements there emerges a stunningly powerful picture of despair, revulsion and brutalisation____The very starkness and simplicity of her approach—no commentary beyond a stern brief introduction—is what makes the book so effective. As a portrait of horror, it is extraordinarily vivid?’ —New Statesman ‘After reading this book of interviews with the soldiers who fought there, I defy anyone to say that Afghanistan was not the Soviet Union’s Vietnam?’ — Independent (Sunday) Zinky Boys Zinky Boys Soviet Voices from the Afghanistan War SVETLANA ALEXIEVICH Translated by Julia and Robin Whitby With Introduction by Larry Heinemann Copyright © 1990 by Svetlana Alexievich Translation copyright © 1992 by Julia and Robin Whitby Introduction copyright © by Larry Heinemann First American Edition 1992 Zinky Boys was first published in the Soviet Union in 1990. SVETLANA ALEXIEVICH 2015 Winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature Contents Introduction Translators’ Preface Short Glossary Notes from my Diary The First Day The Second Day The Third Day Postscript: Notes from my Diary Introduction by Larry Heinemann The stories of soldiers in war are painfully difficult to read, intriguing and bothersome. Oral testimony, simply expressed, is always the first wave of ‘story’ that emerges from any war. Until recently, the publication of a book of stories about the Soviet war in Afghanistan would have been virtually impossible. I have no doubt that novels, poetry, theatre, and films will follow in the years to come when the soldiers find the language and the ‘way’ to tell the story. But for now we have the testimony of ordinary soldiers and platoon officers, women volunteers and gulled civilians who spent time in Afghanistan. And if you don’t mind my saying so, these stories in Svetlana Alexievich’s Zinky Boys read remarkably like the stories that first emerged from American troops retu^ting from Vietnam - this is what I saw, this is what I did, this is what I became. If the war in Vietnam was a benchmark of American history, then the war in Afghanistan can rightly be called an equally dramatic watershed for the Russian empire. (I think we can call it that with a straight face, don’t you?) The contrasts and comparisons between the two wrenching political and historical events will have lasting reverberations for both countries. Though, I suppose we could say that the results of the Soviet Union’s war in Afghanistan were more dramatic, to put it mildly. In late 1989, while the fighting continued, I was fortunate enough to travel to the old USSR with a group of Vietnam veterans and psychologists expert in post- war trauma. We were going to meet and talk with young veterans of the Soviet war in Afghanistan -Afgantsi, they call themselves. We flew into Moscow airport through 10,000 feet of solid overcast. Now, I don’t know about anybody else on the plane, but I felt mighty strange. Flying into Moscow I was literally coming down from a lifetime’s propaganda about the USSR as a place and the Soviets as a people; stories of a bloody, hateful revolution; cycles of crushing famines and virtually endless economic depressions; Communist suppression at least as viciously brutal as life under the tsars; stories of sour-faced and lazy, fat, and selfish commissars ready to grab any good thing out of the hands of ordinary working stiffs, and if they dare criticize anything or speak their minds, throw them into the grinder of the labor camp gulags and work them to death or condemn them to an insane asylum to keep them docile and stupid with plenty of State-approved psychotropic drugs. This was the Soviet Union of my childhood; the paranoid and hideous Stalin purges; the doomed Hungarian revolution of 1956, when the people of Budapest attacked Soviet tanks with their bare hands, Molotov cocktails and small arms captured from the despised secret police; the everpresent threat of tens of thousands of mad-dog troops atop tens of thousands of invincible tanks waiting on the other side of the Iron Curtain just itching to sweep across Europe to enslave a continent, leaving in its wake a devastation of rape, pillage, and murder. Tens of thousands of tactical and strategic nuclear weapons atop launch- ready ICBMs; supersonic bombers poised at the end of runways, their sweptback wings drooping to the tarmac with ‘payload’, ready to leap into the air at a moment’s notice with enough megatons to render the planet dead at the start of a long nuclear winter. I was on the trip because I’d been a soldier once, in Vietnam. I had written about that war, and have since become intimate with the personal reverberations of what being a soldier means. And, too, I’d heard that the Afgantsi had to endure the same military grind as American soldiers in Vietnam, and would no doubt have to endure the same personal reverberations when they got home. I wanted to see for myself what effect the war had on them, and perhaps save them some of the grief I have had to endure. They met us at the airport with astonishing warmth and hospitality, and told us more than once that finally, finally, they had someone to talk to who would understand. I couldn’t help but wonder, hadn’t they been talking to their fathers? But then I remembered the struggling conversations with my own father when I came home from overseas - trying to make sense to him about what had just happened to me. I was surprised and gratified to hear the Afgantsi say, after we’d hung out together for the better part of two weeks, that the only difference between Afghanistan and Vietnam was that Afghanistan was brown and Vietnam was green. We shared the large similarities and the peculiar differences. For instance, the Soviet army did not issue dog tags, so many of the Afgantsi tattooed their blood type on their wrists or shoulders, or carried an empty AK- 471 cartridge on a string around their necks with a piece of paper inside with the name, address, and phone number of their next of kin. Such homemade solutions were commonplace. We met and talked many times in those weeks, the conversations lasting weU into the night, lubricated by liter bottles of vodka (so ice-cold it poured like liqueur). More than a few talked as radically as any angry, bitter, pissed- offVietnarn GI from the late I 960s and early i 970s. They took us to a ‘private’ museum, where among the military artefacts were booby-trapped rag dolls with plastic hands and faces. Who would pick them up? Children, of course. Who would make such a thing? KGB or CIA? Who, indeed? What amazed me and touched me most deeply about the visit, the meetings, and the private talks was that I was talking to men who were young enough to be my own sons. What came through most forcefully was that no matter the nationality - Americans fighting in Vietnam, Soviets in Afghanistan, South African conscripts in Angola, British troops in Northern Ireland, Israelis and Palestinians in the Middle East - the reality of being a soldier is dismally and remarkably the same; gruelling and brutal and ugly. Regardless of the military or political reason (always decisions made by politicians and ‘statesmen’ far removed from the realities of the field), for ordinary everyday grunts the results are always the same; it is soul-deadening and heart-killing work. The eighth-century Chinese poet Li Po probably said it the best of all: . . . sorrow, sorrow like rain. Sorrow to go, and sorrow, sorrow returning. The similarities of the United States’ war in Vietnam and the Soviet war in Afghanistan are striking and ironic, and prove to me that we as people have a lot more in common than we might think. Both wars were fought without the full support or involvement of their country’s citizens. Indeed, before 1985 the Soviets were told their troops were in Afghanistan fulfilling their ‘international duty’ building hospitals and schools,

Description: