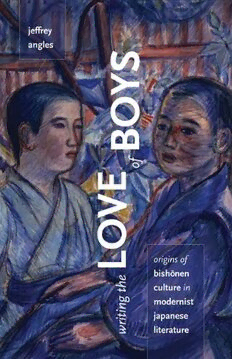

Writing the Love of Boys: Origins of Bishonen Culture in Modernist Japanese Literature PDF

Preview Writing the Love of Boys: Origins of Bishonen Culture in Modernist Japanese Literature

Writing the Love of Boys This page intentionally left blank Wr i ting the Love of Boys Origins of Bishōnen Culture in Modernist Japanese Literature Jeffrey Angles University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London The University of Minnesota Press gratefully acknowledges financial assistance provided for the publication of this book by the Japan Foundation. Copyright 2011 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290 Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Angles, Jeffrey, 1971– Writing the love of boys : origins of Bishōnen culture in modernist Japanese literature / Jeffrey Angles. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn978-0-8166-6969-1 (hc : alk. paper) isbn978-0-8166-6970-7 (pb : alk. paper) 1. Japanese literature—20th century—History and criticism. 2. Homosexuality in literature. 3. Modernism (Literature)—Japan. I. Title pl721.h59a85 2011 895.6´093526642–dc22 2010032182 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer. 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Note about Japanese Names / vii Introduction / 1 1 Blow the Bloodstained Bugle Murayama Kaita and the Language of Personal Sensation / 37 2 Treading the Edges of the Known World Homoerotic Fantasies in Murayama Kaita’s Prose / 75 3 The Appeal of the Strange Same-Sex Desire in Edogawa Ranpo’s Mystery Fiction / 107 4 (Re)Discovering Same-Sex Love Ranpo and the Creation of Queer History / 143 5 Uninscribing the Adolescent Body Aesthetic Resistance in Taruho’s Writing / 193 Conclusion Postwar Legacies / 225 Acknowledgments / 247 Notes / 251 Bibliography / 273 Index / 291 This page intentionally left blank Note about Japanese Names The Japanese names that appear in this book are in the traditional Japanese order, with the surname before the given name; however, when writing about Japanese writers and artists with pen names or distinctive given names, I fol- low the common Japanese convention of referring to them simply by their given name or pen name. For this reason, Murayama Kaita’s name may ap- pear simply as “Kaita” rather than Murayama, Edogawa Ranpo as “Ranpo” rather than Edogawa, and so on. Where the given name is not particularly unusual, as in the cases of Tanizaki Jun’ichirō or Hamao Shirō, I followed the Japanese custom and used only the surname. Sometimes the name Edogawa Ranpo appears in other English-language texts as “Rampo,” with an m,but I kept these instances with an n to better approximate the way the word is written in Japanese. Proper nouns and words that typically appear in English dictionaries are presented without italics and macrons; for example, the capital of Japan is represented “Tokyo” instead of Tōkyō. Other terms from Japanese are italicized and appear with macrons to mark the long vowels. I have given English renditions of the titles of Japanese books and articles. When the English renditions of the titles appear in title case (with all major nouns capitalized), that means there is a published English translation of the work, and I reproduced the title as it appears in the published transla- tion. Readers can consult the bibliography for citations of those English translations. When the English renditions of the titles appear in sentence case (with a capital letter only at the beginning), that means there is no translation available as of the time I wrote this book, and what I give is simply my own English gloss of the Japanese title. vii This page intentionally left blank Introduction Discourses of Desire When Western readers look at the manga (graphic novels) that have been so popular in Japan over the course of the last few decades, they are often struck by how often male–male affection and eroticism appears in their pages. In fact, male–male love has been one of the most important thematic elements in manga, especially manga for adolescent girls (shōjo manga),since the 1970s. One thinks, for instance, of the classics Tōma no shinzō (The heart of Thomas, 1974) by Hagio Moto and Kaze to ki no uta(The song of the wind and the trees, serialized 1976–84) by Takemiya Keiko, both of which present groundbreaking depictions of male–male friendship, jeal- ousy, desire, and eroticism within the all-male world of European boarding schools.1By using flowery images, language ripe with florid overstatement, poetic expressions of desire, and bursts of passion throughout their work, these two manga artists presented same-sex desire and eroticism in a lan- guage that appealed immediately to their young, female readership. At the same time, they also explored society’s tendency to shun same-sex eroti- cism through the reactions of the many schoolboys to the sexually active characters at the heart of their stories. The wild success of these manga were instrumental in forming the mold for many shōjo mangapublished in years to come. Still, where do these modes of depicting love and erotic desire between men come from? Were the passionate, romanticized expressions of school- boy desire found in Hagio’s and Takemiya’s work new in the 1970s? In some 1