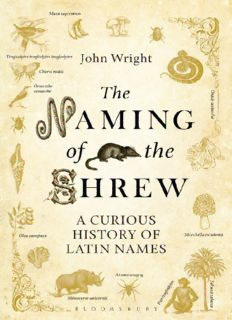

The Naming of the Shrew: A Curious History of Latin Names PDF

Preview The Naming of the Shrew: A Curious History of Latin Names

For Bryan, who knows all the names CONTENTS Prologue I Why do we use Latin Names? II The Names There Are III The Language of Naming IV The Act of Naming V The Rules of Naming VI The History of Naming VII The Father of Taxonomy VIII Taxonomy after Linnaeus IX What is a Species? X The Tree of Life Epilogue Glossary Notes to the Text Bibliography Acknowledgements A Note on the Author Drosera rotundifolia Prologue The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their right names. (Chinese proverb) My best friend at school, Peter, had what seemed to me to be the coolest father in the world. He owned a model aeroplane shop. Every Sunday we would drive in an ancient Volkswagen camper van to the New Forest in Hampshire, where we would fly his wonderful, expensive, radio-controlled models. Occasionally one would make an unwelcome bid for freedom and fly out of radio range. We would have to chase after it, sometimes for miles. As well as model aeroplanes and a healthy obsession with rockets and blowing things up, I had a faint interest in natural history (due entirely, it must be said, to a pathetically doomed attempt to impress a young lady). It was on one of those model aeroplane recovery missions that I came across a tiny and very unusual-looking plant. In fact, there were thousands of them, nestling and glistening in the sandy ground. Leaving the fate of the lost aeroplane in the hands of Peter and an increasingly anxious Peter’s dad, I stopped to dig one out. I took the plant home with me and later looked it up in the library. It was, I discovered, a carnivorous plant, a sundew. A pretty enough name, but the one that caught my attention was italicised next to it: Drosera rotundifolia. It rolled around the tongue – Drosera rotundifolia, Drosera rotundifolia . . . Obviously just a posh name for the sundew, I thought, but what did it mean? Rotundifolia was a simple puzzle: coming from ‘rotund’ and ‘foliage’, it means ‘round leaves’. And, yes, it did have round leaves. Drosera required more study. I learned that it comes from the Greek droseros, meaning ‘dew’, and refers to the tiny, sticky, fly-trapping dewdrops on the ends of the hairs that cover those round leaves. So the name made sense: ‘thing with round leaves covered in dew’. Very neat, and more useful, I thought, than the common name. In addition, the book told me, there were others: Drosera longifolia, the great sundew, and Drosera intermedia, which presumably has leaves whose shape is halfway between the other two (it turned out to be called the oblong-leaved sundew). I was impressed by my discoveries and have never forgotten those three names to this day. I noticed one more thing. After the words ‘Drosera rotundifolia’ there was a single capital ‘L’. Slightly red-faced, I asked the librarian (she was way out of my league) where I might find out what it meant. She needed no book: she told me it was an abbreviation for the name of the man who had first described it. He was called Linnaeus. This eighteenth-century naturalist, she explained, had not only devised the name Drosera rotundifolia, he had created the entire naming system for species. But, entranced by Linnaeus’s inventions as I was, I could not see the point of them – apart, perhaps, from affording me an opportunity of impressing friends, parents and teachers with my erudition (a noble cause). Why, I wondered, would anyone go to the trouble of inventing puzzling names in a foreign, dead language for plants and animals that already had perfectly good common names, especially considering that the Latin ones were difficult to remember and, all too often, difficult to pronounce? It was not only the sundew that I found during my New Forest adventures; even more exciting were the fungi. The one that changed everything was an unprepossessing round, charcoal-like lump attached to an ash tree. It was so dead-looking that I could scarcely believe it was a living thing. Appalled that I had no idea what it was, other than perhaps some sort of fungus, I bought the Observer’s Book of Common Fungi for five shillings, whereupon I discovered that it was Daldinia concentrica, a member of the Pyrenomycetes, that shoots its spores from tiny holes in its surface and was very much alive indeed. My early interest in natural history (thank you Julia, wherever you are) blossomed into a lifelong passion for fungi, and the purpose of Latin names became clear. They are a universal currency across cultures and languages, providing consistent names for both familiar organisms and those organisms that neither have a common name nor ever will. Without Latin names, chaos would rule the science of biology. I still go to the New Forest a dozen or more times every year, but not to fly model aeroplanes. Now my New Forest visits are to take people on fungus forays. My hope is that my companions will come to love the fungi as much as I do, and maybe, just maybe, reconcile themselves to those much feared Latin names. The latter, however, is not always an easy sell. People find Latin names unpronounceable, unmemorable and unhelpful, closing their ears and eyes to them. I think this is a great pity, because they are, in truth, beautiful, fascinating, often amusing and always useful. Latin names of a sort existed long before Carl Linnaeus’s work in the mid- eighteenth century, but it was he who came to use them consistently as simple pairs (known as binomials). These two-part names put each species in its place: the first word indicates the group, or genus, that the species belongs to (sister species share the same generic name, indicating that they belong to the same genus and are therefore close relatives on the ‘tree of life’); the second word – the specific epithet – differentiates the species. Binomials are part of the hierarchy of names developed by Linnaeus: each species nested within a genus, each genus within a ‘family’, each family within an ‘order’, and so on. I impress on people that learning Latin names will enable an ordering of the species in their own minds, because the names themselves reflect that order. Species within a single genus will, on the whole, look similar to one another. And their names often, if not always, tell us something distinctive about them. The slender mushroom Mycena haematopus, for example, produces a red fluid from its stem when broken: pus means ‘foot’ and haemato ‘blood’. Polyporus squamosus is a large, scaly bracket fungus, the underneath of which has thousands of little holes in which the spores are created. Poly is ‘many’, porus means ‘pores’ and squamosus is ‘scaly’. Since people love stories, I also relate to them the sort contained in this book. A favourite (with me anyway) is the one about the genus Cortinarius, which has a dense radiating web of fine fibres covering the young gills. It is called a cortina, from the Latin for ‘curtain’. Some have a white cortina, some a blue cortina, and they all go rusty in the end.* Some Latin names are funny without so painful an exposition: few foragers are able to bring Leucocoprinus brebissonii readily to mind, but none will forget the name of the stinkhorn, Phallus impudicus. In writing this book my aim is to inspire a delight in Latin names. I tell the stories behind the names, how they were devised and what they mean. Above all, these stories are those of the men and women who created them. Where the complexity of the natural world meets the fallibility of the human mind, tales of triumph and disaster, creation and confusion, honour and jealousy ensue. For the scientists and naturalists who create names, there is much to know, much to learn and so very much that can go wrong. The arcane rules that govern the coining and fate of Latin names – many of which were laid down by Linnaeus himself – reflect this perfectly. They are of baroque and strangely endearing complexity. There are, for example, no fewer than fifty rules and recommendations dealing with the seemingly straightforward matter of how authors of plant names are recorded next to the species name (as in the L. for Linnaeus after Drosera rotundifolia). At the very least, in exploring these rules and explaining the reasons for them, I hope to answer the heartfelt complaint of anyone even slightly familiar with Latin names: why, if they are intended to be consistent, do they change all the time? Since Latin names wear their hierarchical nature on their sleeves, the story of how they came into being is best understood against the backdrop of the ancient quest for the ‘natural order’ of the living world (why species seem to come in discreet but related groups rather than an endless continuum). With Darwin, the natural order became clear: it takes the form of a family tree, the mechanism of which is common descent.* However, the work of placing species within that order is a continuing and contentious challenge. Taxonomy, the classification of the living world, of which naming is but a part, is a vibrant and essential discipline within biology, and the image of aged and desiccated specimens being minutely examined by aged and desiccated naturalists belongs to the past. The living world is orders of magnitude more varied and complex than Linnaeus ever suspected, and even fundamental concepts, such as what may or may not constitute a species, can pose questions that remain unanswered. Throughout this book I use the term ‘Latin names’. Many, perhaps most, scientists prefer the description ‘scientific names’. Neither is entirely satisfactory: Latin names are more often of Greek or other non-Latin derivation (they are merely ‘Latinised’), while ‘mass spectrometer’ is as much a scientific name as Quercus robur (European oak). ‘Latinised scientific names of biological species’ is accurate, but hardly convenient. Since Latin names have a bad habit of changing all the time, there are many, many leftover, out-of-date names. For my purposes, they are more priceless treasure than useless clutter, and I use them alongside current, correct names indiscriminately and generally without explanation. The names themselves are the heroes of this book, and I have taken examples from botany, zoology, phycology (algae), bacteriology and more. However, I make no apology for a blatant preference for the names of fungi. I like fungi. Footnotes for Prologue * The rust-brown spores fall from the gills, eventually turning the cortina the same, final, colour as my MkII and both of my MkIIIs. * A natural order is the way in which species are truly ordered, rather than an arrangement of convenience, such as alphabetical order or order by usage (medicinal, perhaps) or by physical characteristics, i.e. the shape of flowers. For most of history the natural order was simply the way God had laid out the world, and common descent, the true natural order, was unimagined.

Description: