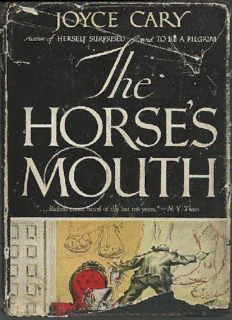

The Horse’s Mouth PDF

Preview The Horse’s Mouth

JOYCE CARY The Horse’s Mouth With a Prefatory Essay by the Author TO HENEAGE OGILVIE Table of Contents Title Page Dedication Prefatory Essay 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 About the Author Copyright Prefatory Essay T HIS book, third and last of a set of three, is the story of an artist, and his adventures both in art and life, told by himself. It has been described as a comedy, and some readers have complained that it is facetious. This is a fair judgment. But Jimson has a reason for being facetious. Anyone who has served in a war knows the man who is suddenly full of jokes on the night before an attack, even just before going over the top. Jimson, as an original artist, is always going over the top into No Man’s Land, and knows that he will probably get nothing for his pains and enterprise but a bee-swarm of bullets, death in frustration, and an unmarked grave. He makes a joke of life because he dare not take it seriously. He is afraid that if he does not laugh he will lose either his nerves or his temper, that he will want to run away from his duty, or demand with rage ‘what is the sense of anything in a world at war,’ and either shoot the nearest officer or himself. He is himself a creator, and has lived in creation all his life, and so he understands and continually reminds himself that in a world of everlasting creation there is no justice. The original artist who counts on understanding and reward is a fool. He may have the luck to be found out by some wind of chance which blows a sympathetic critical talent in his direction; he may be admired and rewarded for what he does not do, but for the very reason that he is original, he will, in the ordinary course of things, wait a long time to be understood. For he has to create not only his work but his public. And the difficulty here is that the public consists also of creative artists. Every living soul creates his own world, and must do so. The human child brings with it very little instinctive equipment for life. It does not even know by instinct that fire burns, or that if it steps out of the window it will fall. It does not know how to communicate, to feed itself, or even what is good to eat. It is a solitary mind from the beginning. It feels love, it feels sympathy, but it does its thinking by itself. It has to create a three-dimensional universe for itself in its own imagination; it has to learn that cups are hollow, balls are round, that the garden wall has another side, and that its two sides are never seen together. And all external objects, even before the child can speak, are full of significance for its feelings. Mother and father, brothers and sisters are each a unique experience, to be seized upon by the imagination and built into a general conception of life. Everything that a boy encounters as he grows up, he ranges for himself in the order of his ideas, his taste, his ambitions, his will. As a grown man he will love like a poet creating a beauty for the soul. When he creates a home, the furniture he buys will seem like no other furniture. He will fiercely resent any attempt to take his home from him or destroy his property, because they are property in the deepest sense, unique to him. He has made them as a whole, and committed himself to them. They are a great, often the chief part, of the world which he has long and painfully constructed for his own pleasure. Now suppose this world includes some art. Suppose he has formed for himself a taste in pictures, poetry and music. Suppose he has given appreciation to (say) Watts, Tennyson and Mendelssohn (or Cézanne, Mallarmé, and Debussy), then these artists are part of his created world. He owns them, he is fond of them, he feels with them, he reveres them as great artists and in that reverence he knows that he too has a share of greatness; his imagination, in front of Watt’s Hope, is suddenly enlarged; he reads Maud and is moved out of a narrow workaday existence into a romantic and exciting world. For this he will probably be despised by most of the next generation who, eager to make a new world for themselves will get their thrills from Cézanne and Mallarmé. The academy painter who abuses modern art is apt to be a joke. He is looked upon as hopelessly narrow-minded. This may be true, but he is not stupid. He realizes that any new art is a danger to his own; if it become the fashion, he may not be able to sell a picture. The history of art shows that tragedy over and over again, and what makes it more pitiful is that very good artists have often been ruined in their lifetime by a change of fashion; and then long after their death, appreciated again. For though fashions in art are unstable like all fashions, there is an underlying reality which will always inform the final judgment. We see that in women’s clothes the final judgment, which separates good periods of dress from bad, is based on the nature of womanhood, her special beauty, and dignity, and power. So great art is always an expression of a fundamental character in things, the simple and powerful emotions which have always dominated and perplexed life. And they are as easily recognized in the arts of ancient India or China as in Cimabue, Renoir or Picasso. But this does not mean that they will be recognized in an artist’s lifetime; or that an artist will be saved from that revolution of boredom or hatred which has destroyed every school of art as a living force, within a generation. Gulley’s old father in this book is taken from life and I, as a boy playing with paint in school holidays, remember very well the feelings of pity and surprise with which I looked at a gilt-framed canvas which he had brought out to show me, and propped against an apple tree among the weeds and cabbage stalks of a Normandy farm garden. I have an idea that it had just come back to him, rejected by the Academy which ten years before had been glad to hang his works. I remember my discomfort, as I realized that this man of fifty or so was appealing for sympathy from me, a boy of sixteen; that there were tears in his eyes as he begged me to look at his beautiful work (‘the best thing I ever did’) and asked me what had happened to the world which had ceased to admire such real ‘true’ art, and allowed itself to be cheated by ‘daubers’ who could neither draw nor glaze; who dared not attempt ‘finish.’ I was myself in 1905 a devoted Impressionist, one of the ‘daubers.’ I thought that Impressionism was the only great and true art. I thought that the poor ruined broken-hearted man weeping before me in the sunlight of that squalid vegetable patch, was a pitiable failure, whose tragedy was very easily understood—he had no eye for colour, no respect for pigment, no talent, no right whatever to the name of artist. I don’t know even now what that man’s work was worth. I suspect from recollection that in these days it would be once more highly appreciated. For several schools have intervened, and having worked through Impressionism and Post Impressionism, the Fauves and the Cubists, we can look upon the late Victorians with a fresh eye and judge them, outside the passing fashion, for what they really were. But that man died long ago in misery, and God knows what happened to his wife and children. J. C. 1 I was walking by the Thames. Half-past morning on an autumn day. Sun in a mist. Like an orange in a fried fish shop. All bright below. Low tide, dusty water and a crooked bar of straw, chicken-boxes, dirt and oil from mud to mud. Like a viper swimming in skim milk. The old serpent, symbol of nature and love. Five windows light the caverned man; through one he breathes the air Through one hears music of the spheres; through one can look And see small portions of the eternal world. Such as Thames mud turned into a bank of nine carat gold rough from the fire. They say a chap just out of prison runs into the nearest cover; into some dark little room, like a rabbit put up by a stoat. The sky feels too big for him. But I liked it. I swam in it. I couldn’t take my eyes off the clouds, the water, the mud. And I must have been hopping up and down Greenbank Hard for half an hour grinning like a gargoyle, until the wind began to get up my trousers and down my back, and to bring me to myself, as they say. Meaning my liver and lights. And I perceived that I hadn’t time to waste on pleasure. A man of my age has to get on with the job. I had two and six left from my prison money. I reckoned that five pounds would set me up with bed, board and working capital. That left four pounds seventeen and six to be won. From friends. But when I went over my friends, I seemed to owe them more than that; more than they could afford. The sun had crackled into flames at the top; the mist was getting thin in places, you could see crooked lines of grey, like old cracks under spring ice. Tide on the turn. Snake broken up. Emeralds and sapphires. Water like varnish with bits of gold leaf floating thick and heavy. Gold is the metal of intellect. And all at once the sun burned through in a new place, at the side, and shot out a ray that hit the Eagle and Child, next the motor boat factory, right on the new signboard. A sign, I thought. I’ll try my old friend Coker. Must start somewhere. Coker, so I heard, was in trouble. But I was in trouble and people in trouble, they say, are more likely to give help to each other, than those who aren’t. After all, it’s not surprising for people who help other people in trouble are likely soon to be

Description: