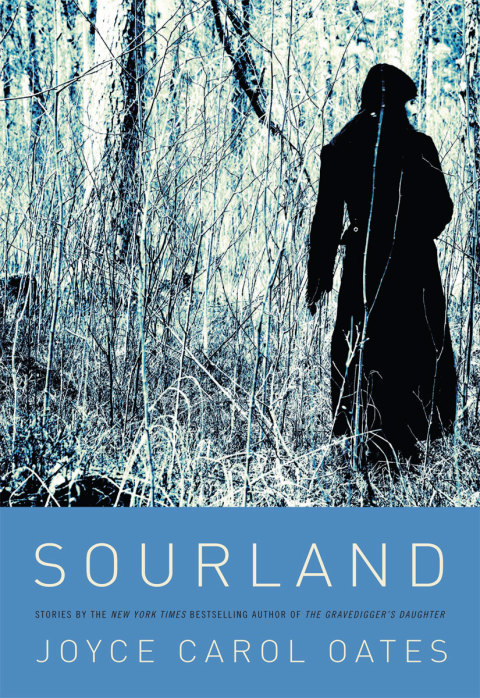

Sourland: Stories PDF

Preview Sourland: Stories

Oates's latest collection explores certain favorite Oatesian themes, primary among them violence, loss, and privilege. Three of the stories feature white, upper-class, educated widows whose sheltered married lives have left them unprepared for life alone. In "Pumpkin-Head" and "Sourland," the widows--Hadley in the first story, Sophie in the second--encounter a class of Oatesian male: predatory, needy lurkers just out of prosperity's reach. In the first story, our lurker is Anton Kruppe, a Central European immigrant and vague acquaintance of Hadley whose frustrations boil over in a disastrous way. In the second story, Sophie is contacted by Jeremiah, an old friend of her late husband, and eventually visits him in middle-of-nowhere northern Minnesota, where she discovers, too late, his true intentions. The third widow story, "Probate," concerns Adrienne Myer's surreal visit to the courthouse to register her late husband's will, but Oates has other plans for Adrienne, who is soon lost in a warped bureaucratic funhouse worthy of Kafka. Oates's fiction has the curious, morbid draw of a flaming car wreck. It's a testament to Oates's talent that she can nearly always force the reader to look.

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Starred Review Oates is a master of the dark tale—stories of the hunted and the hunter, of violence, trauma, and deep psychic wounds. Brilliant in her disclosure of the workings of minds under threat, Oates also possesses a heightened sense of the body's expressiveness, from a man's gait to the smell of his breath to the strength of his grip to the intensity of his stare. Oates grows more insightful, virtuosic, and audacious in her confrontations with fear, pain, and death. Her latest stories of sexual mayhem, family crisis, and shattered identity are barely contained beasts of narration, snorting, pawing, and pulling against the confines of the page. Consider all the adult males preying on innocent girls; or the vicious former model with her “sword-like legs” and poisonous narcissism in “Bonobo Momma”; or the glamorous, young, disabled, and dangerous librarian in “Amputee.” Oates has added a new player to her troupe: the in-shock widow, women who feel exposed and fragile after their male protectors abruptly die, as in “Probate,” a lacerating story of sorrow, absurdity, and breakdown, and “Pumpkin-Head” and “Sourland,” explicit tales of bloodlust and the ecstasy and agony of terror and submission. This is a trenchant book of “cruel fairy tales” in which people are severely tested, profoundly punished, and tragically transformed. --Donna Seaman