Secularism: The Hidden Origins of Disbelief PDF

Preview Secularism: The Hidden Origins of Disbelief

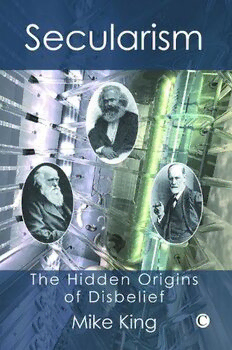

Secularism T h e H i d d e n O r i g i n s o f D i s b e l i e f Mike King C SECULARISM The Hidden Origins of Disbelief Mike King C James Clarke & Co. JCML0510 James Clarke & Co P.O. Box 60 Cambridge CB1 2NT www.jamesclarke.co.uk [email protected] First Published in 2007 ISBN: 978 0 227 17245 2 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record is available from the British Library Copyright © Mike King, 2007 All rights reserved. No part of this edition may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing from the Publisher. JCML0510 Contents Introduction 5 One: Issues in Secularism and Culture 9 1.1 Secularism, Atheism and Scientism 11 1.2 Secularism and Contemporary Culture 18 1.3 Philosophy and Secularism 25 1.4 The Role of Language 28 1.5 Psychology, the Brain and Secularism 36 1.6 The Shibboleths of Secularism 43 Two: Articulating Spiritual Diff erence 45 2.1 The History of the Spiritual Life 50 2.2 Four Spiritual Polarities 59 2.3 The Varieties of Spiritual Impulse 68 2.4 Pathologies and Correctives in the Spiritual Life 72 2.5 The Problem of ‘God’ 82 2.6 The Bhakti / Jnani Distinction 86 Three: Returning to the Roots 90 3.1 The twentieth century 90 3.2 The Enlightenment 117 3.3 The Spiritual Wounds of the West 151 Four: Bhakti and Jnani in Western Development 184 4.1 Piety and the West 184 4.2 Jnani, the East, and Hellenic Infl uence 206 4.3 A Radical History of Western Development 243 Five: The Undefended Western ‘God’ 244 5.1 The Enlightenment Reconsidered 245 5.2 Deism 276 5.3 Failure of the Western Jnani Religion 280 Conclusions 287 References 289 Bibliography 304 Index 311 JCML0510 For Douglas Harding 1909-2007 JCML0510 Introduction This book sets out a radically new exploration of the question: what are the origins of the secular mind? This question has an urgency at the start of the twenty-fi rst century that modernist thinkers of the twentieth century could not have anticipated. According to mainstream Western ways of thinking, religion was a relic of pre- Enlightenment culture, and its disappearance was inevitable, as a fog dispersed by the sun. This ‘sun’, according to the view of the secular mainstream, was science and rationalism. But 9/11, the rise of militant Islam, and the rise of the religious right in America, suddenly made the secular assumption of the death of religion untenable. It became necessary, urgent, even, to att empt a new understanding of religion: everywhere the question of religion has had new debating grounds. But what is missing – and which this book att empts to address – is a new debate about secularism. Painful as it might be, this book takes apart the assumption that science and rationalism are as the sun to the fog of religion and spirituality. The uncomfortable fact needs acknowledgement: that a huge range of scientists and thinkers, from the Enlightenment onwards, fi nd no contra diction between their outer pursuit of science and rationalism, and their inner pursuit of faith and spiritual enquiry. What makes it possible to gradually understand this so-called contradiction is a recognition that ‘religion’ is not the monolithic entity that either Western faith traditions like to assume, or that secularists have inherited as an assumption, exposed as they are mainly to defensive accounts of religion put forward by theologians. This book explores instead the idea of ‘spiritual diff erence’ – religion, or spirituality, as an expression of a wide range of spiritual impulses, some of them congenial to science and rationalism, and some of them deriving instead from the devotional, the moral, the intuitive, the poetic, and the aesthetic. When secularism applies its own well- JCML0510 6 Secularism developed language of pluralism to the phenomenon of religion and spirituality, instead of lazily assuming the monolithic nature of religion, then the fi rst step is taken of engaging with the subject. To taxonomise a domain is to have respect for it. But, crucially, this articulation of spiritual diff erence also allows for a radically new understanding of the origins of the secular mind. In exploring the history of spiritual diff erence the turning point in Western history – the Enlightenment – is reconsidered. Instead of understanding this moment in history as the beginnings of a process that would inevitably bring about the death of religion, we can see instead that the secular mind arose out of a purely negative legacy of that period. It was not the death of religion that was made inevitable by the Enlightenment, but the gradual confounding of its secular legacy. Slowly, it becomes clear that the adventure of secularism has gone wrong by betraying its Enlightenment roots. Secularism became a caricature of Enlightenment thought, an unbalanced extremity of assumption, and, in its forced and reluctant re-engagement with religion, it now has the opportunity to repair a breach in the very fabric of society. This book opens up a conversation between religion and secularism in a way not previously att empted. It sees their apparently opposing worldviews as not intrinsically antagonistic, but only so through accidents of history. Once those accidents are exposed and accounted for as partially wrong turnings, a new rapprochement can take place. But the conversation pursued here has a third partner: the New Age. Usually dismissed by both the other parties, it has elements within it that are important to the debate, particularly its open enthusiasm for the spiritual life. By the term ‘New Age’ the broad phenomenon of new religious movements, adoption of Eastern practices, and revival of pre-Christian religions is meant. Hence we have in this book a conversation, and the development of a vocabulary for the wider dissemination of a conversation, between the secularist, those who pursue faith traditions (‘old religion’), and those who pursue new religions or popularisations of Eastern religious movements. For simplicity, these three groups will be referred to as secularists, religionists, and New Agers: we can understand the new cultural landscape of the twenty-fi rst century as a three-way contest between them. Each group has unique insights and limitations of thought, and a conversation must start with the awkward acknowledgement of those limitations. As this book begins the conversation with the idea of spiritual diff erence, we need to address it through that virtuous hallmark of the secular JCML0510 Secularism 7 era – pluralism. Religionists, secularists and New Agers, each in their own way deny the idea of spiritual diff erence and spiritual pluralism: old religion through its absolutist certainties and war on ‘heresy’; the secular world through indiff erence, and the New Age through an uncritical acceptance of all and everything – its mantra that ‘all is one’. Freud criticised monotheistic religion in particular for its ‘narcissism of minor diff erence’. He meant by this the small diff erences in religious belief that separated groups, which otherwise shared vastly similar ideas, and which could lead to the most appalling violence between them. If we characterise old religion as suff ering from the ‘narcissism of minor diff erence’ then we can characterise secularism as suff ering from the ‘narcissism of self-suffi ciency’, indicating the false belief that humanity had grown up and out of the need for any kind of spirituality (a key shibboleth of secularism). The New Age in turn can be said to suff er from the ‘narcissism of diff erence denied’ – its tendency to downplay spiritual diff erence in the interests of a superfi cial harmony. Chapter One outlines the contours of the contemporary secular worldview, using some case studies in cultural production, including literature and fi lm. It explores the role that science, philosophy, language, psychology and neurology play in constructing the shibboleths of the secular mind. Chapter Two presents a two-fold Model of Spiritual Diff erence to provide the necessary detailed articulation of spirituality for the subsequent chapters. It highlights the diff erence between the devotional and non-devotional spiritual impulse (usefully articulated in Hinduism as bhakti and jnani), and looks at pathologies and correctives in the spiritual life. Chapter Three starts with a detailed consideration of the alienation of the modern, secular mind, and then works backwards through Western history to identify the major factors in the abandonment of religion as a credible cultural force. It considers both the rise of science and the legacy of religious cruelty as factors, and concludes that these were insuffi cient to account for the ‘death of God’. Chapter Four considers the rise of Christianity as a devotional religion with Hebraic roots, as juxtaposed to the Hellenic modality of the spirit: a contrast between the profoundly diff erent spiritualities identifi ed through the terms bhakti and jnani. Chapter Five reconsiders the Enlightenment, not as the triumph of rationalism, but as the re-assertion of a non-devotional world- curious spirituality: the atheist Enlightenment thinker being the JCML0510 8 Secularism exception, not the rule. It is shown that the ‘death of God’ was not intended by almost any serious Enlightenment thinker, but that they defended a conception of ‘God’ that was more Hellenic (or jnani) than Christendom could bear. JCML0510 One: Issues in Secularism and Culture In this chapter we begin our exploration of the secular mind and how it has placed itself beyond any discourse of the spirit in secularism’s overa rching cultural dominance. The word ‘spiritual’ is broadly rejected by the secular mind, and in secular Western culture, permitt ed only to poets whose aesthetic vocabulary requires the use of old-fashioned and vaguely provocative terms. However, at least a place-holder defi nition of spirituality is required here, so we start by saying that it is simply to do with a profound connectedness. Crucial to the understanding of spirituality is the idea that it is multiple, not one; that there exists spiritual diff erence, spiritual pluralism, a variety of spiritual impulse. Its detailed articulation is kept for Chapter Two, and in Chapter Three we will show how it also delineated through the manifestation of its opposite: a debilitating sense of alienation. We are particularly interested to show here how contemporary Western culture refl ects the assumptions, the shibboleths, of secular- ism. A shibboleth is a culturally received but unexamined assumption that is both a requirement of membership and outmoded: the group clings to it for identity but forgets its original meaning. Professor Mike Tucker of Brighton University puts it well: ours is the fi rst culture to proclaim with hubristic certainty that history and politics together constitute the sole ground of our being, and that any sense of the ‘vertical’ or ‘cosmic’ dimension in life is but a reactionary remnant from the irrationalities of pre-Enlightenment thought.1 Tucker is right about politics: it is secularism’s fi rst cultural reality, and we will show that political thinkers, in particular Marx, are amongst the prime architects of the secular mind. Marx eff ectively denied the spiritual or religious interiority of the mind when he said of the human essence: ‘In its reality it is the ensemble of the social JCML0510