Gothic: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting PDF

Preview Gothic: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting

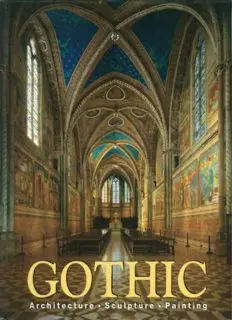

Gothic art originated around 1140 in the Ile-de. France. Initially confined to the cathedrals and the most important abbeys of this region, it was soon to be regarded as a model for the rest of France and finally for Europe as a whole. The new style was not solely confined to the sacral domain, but rather increasingly invaded the secular and private spheres. Gothic is the first art-historical epoch from which art works of all genres have survi.ved. Prominent among these remarkable works are the numerous richly-varied cathedrals, the abbeys and town churches with their sequences of sculptures, colorful windows, wall paintings, gold work and book illuminations. Alongside these, the diverse town sites, the castles and palaces with their elabo rate and artistic furnishings, continue to amaze the modern viewer. The present volume describes the development of Gothic in all its diversity. Beginning with the initial flourishing of Gothic architecture in France, the book traces its early reception in neighboring coun tries. Individual essays are devoted to the specific formal development of Gothic architecture in England, the "German-speaking countries," Italy, Spain, Portugal, northern and eastern Europe as well as texts on late Gothic architecture in France and the Netherlands. The history of Gothic sculp ture and painting with its changing pictorial themes and representational forms is also presented with reference to specific countries. Separate contribu tions on stained glass and gold work and individual studies devoted to special themes - to the Cathar heresy, to the Papal Palace in Avignon, to urban development, to technical knowledge - complete the period's overview. This book's many illustrations match the wide subject range of the Gothic period; approximately two-thirds of the 780 illustrations were especially photographed for this volume. The various art· historical contributions were written exclusively by experts. FRONT COVER: Assisi, Upper Church of San Francesco, 1228-53 Interior view Photo: © 1990, Photo Scala, Florenz BACK COVER: Lausanne, Notre-Dame Cathedral begun last quarter of the 12th century Painted columns and arch Photo: Achim Bednorz COVER DESIGN: Carol Stoffel The Art of GOTHIC 130: 15 ='fl r +3 The Art of Architecture• Sculpture• Painting Edited by Rolf Toman Photography by Achim Bednorz KONEMANN scan: The Stainless Steel Cat FRONTISPIECE: Wells Cathedral Steps to chapter house © 2004 KONEMANN*, an imprint of Tandem Verlag GmbH, Ki:inigswinter Project coordinator and producer: Rolf Toman, Esperaza; Birgit Beyer, Cologne; Barbara Bomgasser, Paris Photography: Achim Bednorz, Cologne Diagrams: Pablo de la Riestra, Marburg Picture research: Barbara Linz, Sylvia Mayer Cover design: Carol Stoffel Original title: Die Kunst der Gotik ISBN 3-8331-1038-4 © 2004 for the English edition KONEMANN*, an imprint of Tandem Verlag GmbH, Ki:inigswinter Translation from German: Christian von Arnim, Paul Aston, Helen Atkins, Peter Barton, Sandra Harper English-language editor: Chris Murray Managing editor: Bettina Kaufmann Project coordinator: Jackie Dobbyne Proofreader: Shayne Mitchell Typesetting: Goodfellow & Egan Publishing Management, Cambridge *KONEMANN is a registered trademark of Tandem Verlag GmbH Printed in EU ISBN 3-~331-1168-2 10987654321 X IX VIII VII VI V IV III II I Contents Rolf Toman Introduction 6 Pablo de la Riestra Elements of Religious and Secular Gothic Architecture 18 Bruno Klein The Beginnings of Gothic Architecture in France and its Neighbors 28 Barbara Borngasser The Cathar Heresy in Southern France 116 Ute Engel Gothic Architecture in England 118 Christian Freigang Medieval Building Practice 154 Peter Kurmann Late Gothic Architecture in France and the Netherlands 156 Christian Freigang The Papal Palace in Avignon 188 Pablo de la Riestra Gothic Architecture of the "German Lands" 190 Pablo de la Riestra Gothic Architecture in Scandinavia and East-Central Europe 236 Ehrenfried Kluckert Medieval Castles, Knights, and Courtly Love 240 Barbara Borngasser Gothic Architecture in Italy 242 Barbara Borngasser Florence and Siena: Communal Rivalry 252 Alick McLean Medieval Cities 262 Barbara Borngasser Late Gothic Architecture in Spain and Portugal 266 Uwe Geese Gothic Sculpture in France, Italy, Germany, and England 300 Regine Abegg Gothic Sculpture in Spain and Portugal 372 Ehrenfried Kluckert Gothic Painting 386 Ehrenfried Kluckert Subjectivity, Beauty and Nature: Medieval Theories of Art 394 Ehrenfried Kluckert Architectural Motifs in Painting Around 1400 402 Ehrenfried Kluckert Narrative Motifs in the Work of Hans Memling 420 Ehrenfried Kluckert Visions of Heaven and Hell in the Work of Hieronymus Bosch 424 Ehrenfried Kluckert Gold, Light and Color: Konrad Mitz 438 Ehrenfried Kluckert The Depictions of Visions and Visual Perception 439 Ehrenfried Kluckert The Path to Individualism 454 Brigitte Kurmann-Schwarz Gothic Stained Glass 468 Ehrenfried Kluckert Medieval Learning and the Arts 484 Harald Wolter-van dem Gothic Goldwork 486 Knesebeck Appendix 501 OPPOSITE: Chartres, Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Bourges, Cathedral of St.-Etienne, begun after the fire of 1194 begun late 12th century View from the south Ambulatory Rolf Toman Introduction "Anyone making their way to Chartres can see from a distance of some thirty kilometers, and with many hours of walking still ahead, just how this city crowns the area solely through the great mass of its cathedral with its two towers-it is a city-cathedral. It was a busy city throughout the Middle Ages because of its cathedral, and today the town is an image of what a cathedral town once was. And that was? • - -,, It was a world which lived through and with its cathedral, where houses huddled below the cathedral and where streets converged at the cathedral, where people turned from their fields, their meadows, or their villages to gaze at the cathedral. .. The peasant might inhabit a lowly hut and the knight a castle, but both shared in the life of the cathedral to the same extent and with the same feelings during its long-drawn-out construction over the centuries, during its slow rise ... Everyone without exception shared the common life of the cathedral. No man was imprisoned in his own poverty at night without being aware that outside, whether near or far, he too possessed riches." In this observation from his Open Diary 1929-1959, the Italian element: his book on cathedrals is closely linked, in date and in writer Elio Vittorini expresses a common longing for an ideal world, philosophy, with his ultra-conservative work on cultural criticism, an intact world in which meaning is implicit. The 19th-century Art in Crisis: The Lost Center (1957, original German 1948), whose Romantics (Victor Hugo, Fran~ois Rene Chateaubriand, Friedrich dubious racial and ideological underpinnings are unmistakable. Schlegel, Karl Friedrich Schinkel, John Ruskin, and many others) The affinity between conservative cultural criticism and an were also deeply moved by the sight of Gothic cathedrals, and the inflated reverence for Gothic has a long tradition in Germany. That Romantics' intense vision of the spirituality and transcendent Gothic lends itself to ideology in this way is closely connected with character of the vast and soaring spaces of Gothic cathedrals has the long-standing belief that Gothic, in contrast to Romanesque, is lasted to the present day. It is apparent, for instance, in the noted the true German style. Based on an error, this appropriation of 20th-century scholar of Gothic Hans Jantzen (from whose The Gothic was, in the final analysis, "founded in the art theory of the Gothic of the West this introductory quotation from Vittorini has Italian Renaissance, which had considered medieval art in general to been taken), who is still part of the Romantic tradition. This is be an essentially 'German' or-which comes to the same thing evident in such characteristic assertions that in Gothic architecture Gothic style, from which the new Renaissance art of Italy had now "something solid is being removed from its natural surroundings by finally liberated itself. As late as around 1800, equating Gothic with something incorporeal, divested of weight and made to soar German was a topos of European culture, one that was scarcely ques upwards," as well as by his famous analysis of the "diaphanous tioned. From this there arose in Germany a national enthusiasm for structure" of the Gothic wall and his talk of "space as a symbol of the everything Gothic, in which people thought they saw the greatest spaceless." The theme is always the transcendent. achievement of their forebears ... But then art history, which was just This aspect of the Gothic cathedral was also important to the emerging as a discipline, quickly established that Gothic, especially scholar Hans Sedlmayr, who shortly after World War II published his the Gothic cathedral, was one of the original achievements of celebrated study, The Emergence of the Cathedral (1950). Sedlmayr Germany's arch-enemy of the time, France. This bitter recognition led was attempting to offset the darkness of his own time with the shining to a change of attitude in the evaluation of the German Middle Ages" light of the cathedral, which he saw as a complex and multifaceted (Schutz and Muller). work that marked a high point of European art. Just as Jantzen had The reason for this disillusionment lay in thinking in terms of "discovered" the diaphanous wall structure, so Sedlmayr, turning his national superiority, an error from which even some art historians gaze upwards to the vaults, identified what he called the "baldachin were not immune. It is astonishing-and important to remember system" of Gothic cathedrals (the vaults looking like a canopy just how stubbornly this brooding over the ethnic origins of Gothic supported by slender columns). But alongside all the structural anal persisted. Such views can be detected even in Sedlmayr's book on ysis and the metaphysical interpretation, Sedlmayr added another cathedrals, though they are more subtle than the ones in circulation 7 St.-Denis, former Benedictine abbey church, detail of stained-glass window with Abbot Suger at the feet of the Virgin in Nazi Germany, and seemingly expressed in more civilized terms. In Sedlmayr's summary of his deliberations on the origin of the Gothic cathedral we are told: "For the complete structure of the cathedral, the north Germanic ('Nordic') element provided the structural component, the skeleton, as it were. The so-called Celtic ('Western') element provided the 'Poetic.' And the Mediterranean ('Southern') element provided the fully rounded, human component... Histori cally these elements did not appear simultaneously during the construction of the cathedral, but in this sequence... The third element, however, was already in play from the beginning but initially superimposed on the others and largely ineffective. Only after 1180 does it flourish, determining the 'classic phase' of the cathedral, but from as early as 1250 onwards it was firmly suppressed again. The 'classic' cathedral is thus one of the most magnificently successful fusions of the characters of three peoples. In art it creates 'Frenchness,' and in this very fusion is European in the highest sense." Today this biological, ethnic, and racial delving or as Wilhelm Worringer named and practiced it-this delving into "the psyche of mankind" in order to explain the "essence of the cathe dral" is considered obsolete. A major obstacle in our attempt to understand the art and life of the Middle Ages is the difficulty of putting ourselves into the intellec tual and emotional world of the men and women of the period. The decisive barrier to our understanding is presented by medieval Chris tianity, which, embracing every aspect of life, completely determined the thinking and feeling of the period. Today we are even farther away from this aspect of medieval life than the Romantics were. This diffi that of his neighbors to the southwest and east, the counts of Cham culty was noted by Sedlmayr in his afterword published in 1976 in a pagne. What distinguished him from the other feudal lords, however, reprint of his book on cathedrals. For Sedlmayr there was no point in and gave him greater authority, was the sacred character conferred saying "We must look at the cathedral through the eyes of medieval on him when, at his coronation, he was anointed with holy oil. people" because these people would inevitably be an abstraction. This potential was something which Suger of St.-Denis (ca. Instead, he suggested "looking at the cathedral through the eyes of its 1081-1151), one of the leading figures of France in the 12th century, builders, with the eyes of Suger and his architects." This was a clear knew how to exploit. Although of humble origin, he was a childhood cut task and methods could be developed to achieve it. Even if friend of Louis VI from the time of their common monastic Sedlmayr's optimism is not something we can fully share, it is this upbringing in the abbey of St.-Denis, and he was a confidant, advisor approach we have taken here; and we can begin by turning our atten and diplomat in the service of both Louis VI ( 1108-3 7) and Louis VII tion to the origins of Gothic and the central role played by Abbot (1137-80). When Louis VII and his queen took part in the Second Suger of St.-Denis. On this, at least, art historians are in agreement. Crusade from 1147 to 1149 he appointed Suger his regent, a role Suger performed extremely well. As the monk Willelmus, Suger's Abbot Suger of St.-Denis: The Beginnings of Gothic biographer, reports, from that time on Suger was known as "the Gothic is of French origin. It emerged around 1140 in the small father of the fatherland." He made the strengthening of the French kingdom, which already bore the name Francia, that occupied the monarchy his life's work. Aware that the temporal power of the area between Compiegne and Bourges, and that had Paris, the royal French king was greatly restricted, he knew that it was vital to city, as its center. The territory on which the most impressive cathe increase the monarchy's spiritual prestige. Suger's efforts were aimed drals in the new Gothic style were to be built in quick succession was at exactly this. insignificant compared with present-day France, and the power of When he became abbot of St.-Denis in 1122, Suger, along with the French king-though not the prestige-was still slight. His polit all his other tasks, doggedly pursued his dream of restoring the ical and economic power took second place to that of the dukes of abbey's former prestige by renovating the long-neglected fabric of the Normandy, who were at the same time kings of England, and also to church. The church had already been a royal burial place under the 8