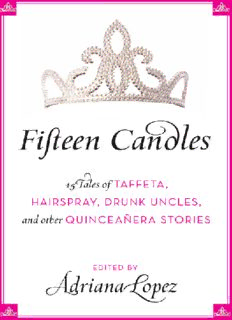

Fifteen Candles: 15 Tales of Taffeta, Hairspray, Drunk Uncles, and other Quinceanera Stories PDF

Preview Fifteen Candles: 15 Tales of Taffeta, Hairspray, Drunk Uncles, and other Quinceanera Stories

Fifteen Candles 15 Tales of Taffeta , Hairspray, Drunk Uncles , and other Quinceañera Stori es an anthology edited by L Adriana opez F or my mother and her fortitude, when it seemed everyone in my peer group was considering a jump off a bridge . . . Table of Contents vii AN INTRODUCTION The Romantics 3 29 51 Alberto Rosas Angie Cruz Constanza Jaramillo-Cathcart el quınceañero love rehearsals fıfteen and the mafıa Qu eens for a Day 71 92 106 Fabiola Santiago Leila Cobo-Hanlon Nanette Guadiano-Campos the year of ıt all started uprooted dreamıng: a tale wıth the dress of two quınceañeras The Party Crashers 131 151 175 Malín Alegría-Ramírez Adelina Anthony Eric Taylor-Aragón quınce crashers la mamasota barefoot Reluctant Damas & Chambelanes 203 222 239 Barbara Ferrer Michael Jaime Becerra Monica Palacios no quınces, the perpetual the dress was way thanks. chambelán too ıtchy The Dreamers 267 288 308 Felicia Luna Lemus Berta Platas Erasmo Guerra quınce never was a blue denım recuerdo: quınce my sıster remembered 327 CONTRIBUTORS 333 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ABOUT THE AUTHOR CREDITS COVER COPYRIGHT ABOUT THE PUBLISHER An Introduction I can’t remember my fifteenth birthday. I was probably punished as usual, locked up in my Laura Ashley–wallpapered room, sob- bing to my Culture Club poster, asking: “Why me? Why? ” Life ’s emotional arc seemed so extreme back then. Like a poorly devel- oped plot to an MTV music video or an after-school special whose storyline was equally as calamitous as my own life ’s. It ’s all a lot of information to take in for a new adult brain. Circa XV, you’re basically a fully formed person conscious of your surroundings. A bit precocious? Yes. Strange? Absolutely. But nonetheless, you still have a pretty clean slate to be proud of. You’re ripe with ideas about the world and you’re at your physical prime. Yet despite these attributes, you’re absolutely helpless, use- less, for two fundamental reasons: 1) your flaming hormones won’t let you think straight, and 2) you’re still a citizen of the re- public of the family home. You’re basically stuck giving in or de- fecting. On the edge of adulthood, turning fifteen can pose many exis- tential questions about your future role in society. Especially when the deep-seeded symbolism of the quinceañera ritual is involved. This ultimate coming-out party for Latinas in the States and in Latin America has always, and will always remain, a rite of pas- sage to cherish forever or relive in therapy first, and eventually grow from (most of this collection’s contributors belong to the latter group). This ostentatious girl-to-woman transformation tradition has vii AnI ntroduction been hard to shake for Latinos since its rougher beginnings in Aztec culture, where fifteen-year-old girls were feted for being ready for marriage and procreation, and boys for war. After Eu- rope spread its influence over the Americas, quinceañera parties for upper-crust debutantes had more of a cotillion bent to them. This formal introduction of rosy-cheeked girls to society included the not-so-Latin-American waltz and usually came with a crown, a fancy gown, and fifteen dancing couples. In the last decades, having a quinceañera party has gone in and out of fashion like any gyrating teen heartthrob of the day. But in the last few years, cities all across the United States have witnessed quite the quinces comeback. Call it a case of major Latin pride, or Bat Mitzvah and Sweet Sixteen envy, but flocks of Latinos are res- urrecting this ritual to all-new millennium heights with ceremo- nies as opulent as a Dynasty wedding. Pyrotechnics aside, we ’re still a traditional people and most of the quinceañeras’ earmarked traditions still linger, albeit with new twists for our multiculti times. Some families still opt for modest backyard parties, some do it up in big catering hall parties, some rent out Disney World, and some prefer a reflective religious ceremony. But all include the girl, her family and friends, the big expectations, the nerves, and eventually the messy mush of memories. It doesn’t matter whether you were the only Latino family in town or if your neighborhood grocery had a fully stocked Goya foods section, if you lived in the States, a quinceañera party affirmed your Latinoness. And at fifteen, many writers from this collection weren’t sure about this multigenerational-Latino- Catholic-formal-dance-party-with-free-alcohol thingamajig. It could be kind of surreal for the average young Latino. Maybe you’d been to a wedding or two in your youth, but this was about celebrating a peer’s initiation into the trappings of adulthood. No groom in sight, just God. “I mean, gosh!” the average preteen An Introduction viii might ponder, “there’s this holy reception first, then we’re at this huge party, she’s suddenly wearing makeup and jewelry, she’s waltzing, she’s followed around by girls in matching dresses and dudes in tuxes, her father dances with her and then encourages her to dance with other guys, and she’s trading in her flat slippers for sexy heels?!” Whether you’re related to the quinceañera, dating her, in love with her mother, a friend of a friend of hers, or just there for the free food, you’re still at this function asking yourself questions about where you fit into this spectacle. Under the heel-beaten floorboards of this seemingly harmless fiesta lie bigger, thornier issues for the preteen Latino to consider: the curiosities of cultural traditions, recurring acne, the church, appropriate dancing tech- niques, peculiar relatives, covert drinking, unflattering formal at- tire, the opposite sex, the stereotypes and mandates of your own sex and, most importantly, whether this means you’re now allowed to have sex. In my search for fifteen writers with a personal story to tell about a quinceañera event in their lives, I found the majority of tales fell into five types of categories: the writer who had a party, the writer who was forced to have a party, the writer who dreamed about a party, the writer who was serendipitously invited to or crashed a party, and the writers asked to be a dama (pseudo-brides- maid) or a chambelán (quasi-groomsman) in the quince- añera’s court (adolescent bridal party). I was thankful for the bounty of story submission ideas I received, and was relieved that there were plenty out there with a fun-loving sense of humor will- ing to be frank about the freaky stuff that had happened to them on the way to Quincelandia. Aiming to steer clear of monochromatic depictions of the quinceañera event, I’m proud to say that Fifteen Candles’ contrib- utors are as motley as that ’80s rocker “crue.” They vary by gender, orientation, social class, region of the Americas, and gen- ix An Introduction eration. And though they were chosen for their originality in voice, experience, and point of view, in the end, their stories are all surreptitiously linked by humor, sadness, and a lot of self- discovery. For those looking for a how-to book for planning a quince- añera bash, please put this book down; this was not intended for you. The parties depicted on these pages aren’t always that pretty. Fifteen Candles aims to poke fun at the ritual, question it, re-imag- ine it, challenge it, and see it through the eyes of a newcomer. Di- vided into five thematic sections, these are candid snapshots of fifteen writers looking back on their former, younger selves, try- ing to understand what it meant. For some, such as in the opening section, The Romantics, a hor- monal high seemed to have propelled them through their experi- ence. Writer Angie Cruz relives a shrouded first kiss with a chambelán so cute, he could have been in Menudo, while actor and lawyer Alberto Rosas cursed with looking like Antonio Banderas, accidentally seduces both quinceañera and her mother. And teacher and writer Constanza Jaramillo-Cathcart considers the reason her dashing, white-suited date to a Bogotá quince never called again might have had something to do with his family’s ties to the mob. But of course there were others who had no time for flirt- ing with all the responsibility they had to deal with. In the second section, Queens for a Day, these are the writers who had to grin and bear it as the quinceañera in headlights, ahem, spotlights. Res- urrecting uncensored pages from her lock-and-key diary, journal- ist Fabiola Santiago reflects on her humble party and compares it to how her three very different daughters chose to turn fifteen themselves. Editor Leila Cobo-Hanlon knew from the get-go her dress had to be emerald green or she would go naked. Finding that color was tough, but convincing the cool kids from school to at- tend her house party was even tougher. Teacher and poet Nanette

Description: