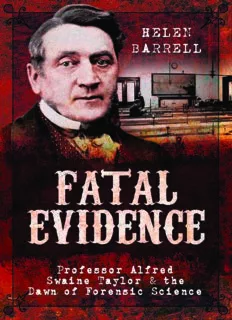

Fatal Evidence: Professor Alfred Swaine Taylor & the Dawn of Forensic Science PDF

Preview Fatal Evidence: Professor Alfred Swaine Taylor & the Dawn of Forensic Science

Fatal Evidence Fatal Evidence.indd 1 01/06/2017 19:14 One day a shepherd was crossing the bridge when he saw a little bone beneath him in the sand. It was so pure and snow-white that he wanted it to make a mouthpiece from, so he climbed down and picked it up. Afterward he made a mouthpiece from it for his horn, and when he put it to his lips to play, the little bone began to sing by itself: Oh, dear shepherd You are blowing on my bone. My brothers struck me dead, And buried me beneath the bridge. From ‘The Singing Bone’, collected by The Brothers Grimm. Translated by Professor D.L. Ashliman Fatal Evidence.indd 2 01/06/2017 19:14 Fatal Evidence Professor Alfred Swaine Taylor & the Dawn of Forensic Science Helen Barrell Fatal Evidence.indd 3 01/06/2017 19:14 First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Pen & Sword History an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd 47 Church Street Barnsley South Yorkshire S70 2AS Copyright © Helen Barrell 2017 ISBN 978 1 47388 341 3 The right of Helen Barrell to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Typeset in Ehrhardt by Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire Printed and bound in Malta by Gutenberg Press Ltd. Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe. For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED 47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk Contents Note on Text vi Introduction vii Chapter 1 Go Thy Way, Passenger 1 Chapter 2 More of Impulse than Discretion 12 Chapter 3 Fearful and Wonderful 19 Chapter 4 The Light of an English Sun 26 Chapter 5 One of the Most Eminent Men 36 Chapter 6 My Heart is as Hard as a Stone 48 Chapter 7 The Means of our Preservation 58 Chapter 8 The Only Friend I had in the World 69 Chapter 9 The Formidable Scourge 79 Chapter 10 His Very High Position 91 Chapter 11 Romantic, Mysterious, and Singular 103 Chapter 12 Enter Not into the Path of the Wicked 113 Chapter 13 Truth Will Always Go the Farthest 143 Chapter 14 Grieved Beyond all Endurance 151 Chapter 15 You are the Villain 166 Chapter 16 Blood Enough 179 Chapter 17 The Eminent Opinion of Professor Taylor 190 Timeline 204 Acknowledgements 206 Further Reading 207 Selected Bibliography 208 Notes 213 Index 225 Fatal Evidence.indd 5 01/06/2017 19:14 Note on Text Medical jurisprudence Taylor called himself a ‘medical jurist’ practising ‘medical jurisprudence’ – the intersection of medicine and the law. He sometimes described himself as a toxicologist. Had he lived today, he would have been called a pathologist, or a forensic science technician. The Old Bailey The Central Criminal Court stands on a London street called the Old Bailey; this is the name by which the court is commonly known. In newspaper and trial reports, the name can switch about from the Central Criminal Court to the Old Bailey. To avoid confusion, the Old Bailey is used throughout. Inquests In England and Wales, sudden, violent, or unnatural deaths are investigated by a coroner. In Taylor’s day, a jury would hear the evidence and come to a verdict. On finding wilful murder against a particular individual, the case would go to trial if a grand jury decided that it was strong enough. Even if the inquest jury’s verdict was wilful murder, the case could still be thrown out and the accused could go free, or be tried on a lesser charge. If the jury found that the death was the result of natural causes but the coroner strongly suspected otherwise, further investigations would be carried out by police and magistrates. The Crown Under the legal system in England and Wales, the prosecution is said to be the Crown (hence the trial of William Palmer is R v Palmer; the R standing for ‘Regina’, Latin for ‘Queen’). Prosecution witnesses are therefore ‘witnesses for the Crown’. To avoid confusion for international readers, ‘prosecution’ is used in this book instead of ‘the Crown’. Taylor often used ‘prosecution’ instead of ‘Crown’ in his writing. Fatal Evidence.indd 6 01/06/2017 19:14 Introduction A body has been found. There are severe head injuries, as if the victim has been trampled to death. It’s manslaughter, possibly murder. There’s a suspect, and their hobnail boots are covered in something red. Could it be blood? The boots, and snippets of the victim’s hair, are sent to a laboratory for analysis. It is blood on the boots, and there are fibres in the mud around the hobnails, which, under a microscope, match the victim’s hair. There are strands of red wool in the coagulated blood, and further information says that the victim wore a red scarf. The analysis has shown that the victim was probably killed by whoever wore the boots, and the suspect is arrested. This did not happen last week, neither is it a scene from a crime drama on television. It took place in 1863, and the analysis was performed by Dr Alfred Swaine Taylor, professor of medical jurisprudence, toxicology and chemistry at Guy’s Hospital in London. Codes and laws applied to medicine and the examination of violent death go back a long way in human history, as far as Ancient Babylon. It was in Renaissance Europe that legal codes around medicine and violent death were further developed, creating the basis for what we recognise as forensic science today. Britain lagged behind until the early nineteenth century, when advances in science and technology led to the merging of medicine and chemistry and the development of a new science: forensic medicine. Alfred Swaine Taylor, skilled as a chemist and a physiologist, was one of the first, and youngest, lecturers of medical jurisprudence in England. Taylor is remembered today as a toxicologist, involved in the sensational trials of medical men Palmer and Smethurst. They were notoriously difficult cases. Palmer was thought to have poisoned with strychnine, and scientific opinion differed angrily as to how it could be traced. In Smethurst’s case, a test for arsenic that was thought to be infallible was shown to be flawed. But there is far more to Taylor than that. Taylor worked on hundreds of cases from the 1830s to the 1870s, rising to prominence in England as a leading expert. It was, perhaps, his prolific writing output – his cacoethes scribendi, as one of his rivals put it – that helped him to assume his respected position. His opinion was sought by the Home Office Fatal Evidence.indd 7 01/06/2017 19:14 viii Fatal Evidence on difficult cases, and local newspapers proudly announced if a coroner had summoned Taylor’s aid. He became a household name. No diaries of Taylor’s have survived, and neither have any bundles of personal letters, although the occasional piece of correspondence turns up in archives. He was so busy writing books and articles that he had no time to write his memoirs. But the curious can piece together his professional life through newspaper reports of the inquests and trials that he appeared at, and the inside information that sometimes slips through in his books and articles. Glimpses of his personality flash through in his writing: his scathing sarcasm aimed at his professional peers who had the temerity to cross him, his fondness for wordplay, and his rage at the stubbornness of governments who prioritised commerce over public safety. Genealogical records allow us to occasionally press our noses up against the window of his home. For the most part it was a haven, even if tragedy visited his wife’s family, and the occasional policeman and surgeon knocked at his door with a grim burden for his analysis. This is both Taylor’s biography and the story of forensic science’s development in nineteenth-century England; the two are entwined. There are stomachs in jars, a skeleton in a carpet bag, doctors gone bad, bloodstains on floorboards, and an explosion that nearly destroyed two towns. This is the true tale of Alfred Swaine Taylor and his fatal evidence. Fatal Evidence.indd 8 01/06/2017 19:14 Chapter 1 Go Thy Way, Passenger 1806–31 Take notice, roguelings A lfred Swaine Taylor was born on 11 December 1806, in Northfleet, Kent, the first child of Thomas and Susannah Taylor. The small town on the chalky banks of the river Thames is about 25 miles east from the centre of London, and was known in the early nineteenth century for its watercress and flint. Taylor’s maternal grandfather, Charles Badger, had been a wealthy local flint knapper, supplying the essential component for flintlock pistols. Taylor’s father was a captain in the East India Company, and perhaps moved to Northfleet from his native Norfolk when, in 1804, the company leased twelve moorings in the town for its ships. Taylor’s middle name, Swaine, presumably harks back to an ancestor on his father’s side as he had several relatives with the same middle name. Just after Taylor’s second birthday, he was joined by a brother, Silas Badger Taylor. There were to be only two Taylor children; their mother died aged 37, in December 1815, three days before Taylor’s ninth birthday. Her headstone can still be found in the churchyard at Northfleet. It reads: ‘She was worthy of example as a Wife a Mother and a Friend. Go thy way passenger and imitate Her whom you will some day follow.’ By 1818, Taylor’s father had become a merchant, half of Oxley and Taylor, who were based at the chalk works in Northfleet. They advertised themselves as ‘exporters and dealers in all sorts of flints, rough or manufactured, chalk etc, to India, and all parts of England’. The company would later expand to include an office off Lombard Street in London, and Silas would grow up to continue their father’s business. By the 1830s, Oxley and Taylor would sell guns, and were travel agents, selling berths on ships bound for New York. Taylor was a studious boy, not considered strong enough for the rough and tumble life of a public school. Soon after his mother’s death, he was sent to Albemarle House, the school of clergyman Dr Joseph Benson. Located in Hounslow, on a major stagecoach route to the west of London, it was a journey of about 40 miles from Northfleet. Pupils from across the country could reach the school with ease, and its semi-rural location was healthier than the city or town. Albemarle House, Fatal Evidence.indd 1 01/06/2017 19:14