Disraeli: The Novel Politician PDF

Preview Disraeli: The Novel Politician

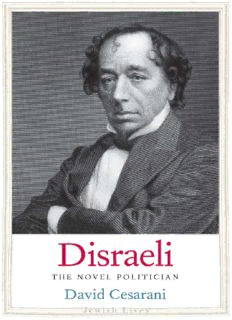

disraeli Disraeli The Novel Politician DAVID CESARANI New Haven and London Frontispiece: Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield, by or after Daniel Maclise, circa 1833. © National Portrait Gallery, London Copyright © 2016 by David Cesarani. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] (U.S. office) or [email protected] (U.K. office). Set in Janson Oldstyle type by Integrated Publishing Solutions. Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2015953578 ISBN: 978-0-300-13751-4 (cloth : alk. paper) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 contents Acknowledgments, vii Introduction, 1 Part One. Becoming Disraeli, 1804–1837, 7 Part Two. Being Dizzy, 1837–1859, 83 Part Three. The Old Jew, 1859–1881, 159 Conclusion: The Last Court Jew, 225 Notes, 237 Index, 283 This page intentionally left blank acknowledgments I would like to thank Anita Shapira and Steve Zipper- stein, the editors of this series, who commissioned the book and whose comments made it better than it would otherwise have been. I owe a double debt to Todd Endelman. His schol- arship paves the way for anyone interested in Disraeli’s Jew- ishness and his Anglo-Jewish milieu, but he also read the man- uscript and made numerous valuable observations. I want to express my heartfelt appreciation to the staff of the London Library and to all those who keep that remarkable institution in rude health. At a time when university libraries have become “information centres,” when even the British Library (where Isaac D’Israeli spent much of his time) resembles a glorified internet café, the London Library stands out as a haven for scholarship and contemplation. At that institution, which was founded during Disraeli’s lifetime and is associated with many who knew him, I found it possible to locate on its shelves al- acknowledgments most everything necessary for my research, while the building, like Hughendon Manor, exudes an aura that helps one connect with the world he knew. I would also like to thank Ileene Smith and Erica Hanson at Yale University Press and Lawrence Ken- ney for his excellent editorial work on the manuscript. viii Introduction Does Benjamin Disraeli deserve a place in a series of books called Jewish Lives? It would certainly be possible to construct one narrative of his life that piled up evidence of his attachment to the people from whom he sprang. Although his story was so extraordinary—so like the plot of one of his own novels as to be sui generis—many Jewish writers did just this after his death and celebrated him as a representative Jew. Many anti-Semites did the same, though of course for different reasons. This version stresses the fact that he was born a Jew and raised as one until he was thirteen years old, when he was bap- tised on the instructions of his father. Although he thereafter identified himself religiously as a member of the Church of En gland, he never denied his origins and never changed his name, which advertised his ties to both his family and his peo- ple. Moreover, he made a perilous trip to Jerusalem in his youth 1

Description: