Can Dietary Modification Alleviate the Burden of CKD? PDF

Preview Can Dietary Modification Alleviate the Burden of CKD?

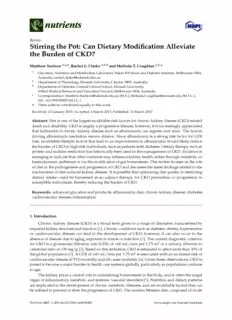

nutrients Review Stirring the Pot: Can Dietary Modification Alleviate the Burden of CKD? MatthewSnelson1,*,†,RachelE.Clarke1,2,† andMelindaT.Coughlan1,3,* 1 Glycation,NutritionandMetabolismLaboratory,BakerIDIHeartandDiabetesInstitute,Melbourne3004, Australia;[email protected] 2 DepartmentofPhysiology,MonashUniversity,Clayton3800,Australia 3 DepartmentofDiabetes,CentralClinicalSchool,MonashUniversity, AlfredMedicalResearchandEducationPrecinct,Melbourne3004,Australia * Correspondence:[email protected](M.S.);[email protected](M.T.C.); Tel.:+61-399030005(M.T.C.) † Theseauthorscontributedequallytothiswork. Received:23January2017;Accepted:6March2017;Published:11March2017 Abstract: Dietisoneofthelargestmodifiableriskfactorsforchronickidneydisease(CKD)-related deathanddisability. CKDislargelyaprogressivedisease;however,itisincreasinglyappreciated that hallmarks of chronic kidney disease such as albuminuria can regress over time. The factors drivingalbuminuriaresolutionremainelusive. SincealbuminuriaisastrongriskfactorforGFR loss,modifiablelifestylefactorsthatleadtoanimprovementinalbuminuriawouldlikelyreduce theburdenofCKDinhigh-riskindividuals,suchaspatientswithdiabetes. Dietarytherapysuchas proteinandsodiumrestrictionhashistoricallybeenusedinthemanagementofCKD.Evidenceis emergingtoindicatethatothernutrientsmayinfluencekidneyhealth,eitherthroughmetabolicor haemodynamicpathwaysorviathemodificationofguthomeostasis. Thisreviewfocusesontherole ofdietinthepathogenesisandprogressionofCKDanddiscussesthelatestfindingsrelatedtothe mechanismsofdiet-inducedkidneydisease. Itispossiblethatoptimizingdietqualityorrestricting dietary intake could be harnessed as an adjunct therapy for CKD prevention or progression in susceptibleindividuals,therebyreducingtheburdenofCKD. Keywords: advancedglycationendproducts;albuminuria;diet;chronickidneydisease;diabetes; cardiovasculardisease;inflammation 1. Introduction Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a broad term given to a range of disorders characterised by impairedkidneystructureandfunction[1]. Chronicconditionssuchasdiabetes,obesity,hypertension or cardiovascular disease can lead to the development of CKD; however, it can also occur in the absenceofdiseaseduetoaging,exposuretotoxinsorinfection[1]. Thecurrentdiagnosticcriterion for CKD is a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 or a urinary albumin to creatinineratioof>30mg/g[2]. Basedonthisdefinition,CKDisestimatedtoaffectmorethan10%of theglobalpopulation[3]. AGFRof<60mL/minper1.73m2isassociatedwithanincreasedriskof cardiovasculardisease(CVD)mortalityandall-causemortality[4]. Giventheseobservations,CKDis poisedtobecomeamajorburdentohealthcaresystemsglobally,particularlyaspopulationscontinue toage. Thekidneyplaysacentralroleinmaintaininghomeostasisinthebody,andisoftenthetarget organofinflammatory,metabolicandsystemicvasculardisorders[5]. Nutritionanddietarypatterns areimplicatedinthedevelopmentofchronicmetabolicdiseases,andaremodifiablefactorsthatcan beutilisedtopreventorslowtheprogressionofCKD.ThemodernWesterndiet,composedoffoods Nutrients2017,9,265;doi:10.3390/nu9030265 www.mdpi.com/journal/nutrients Nutrients2017,9,265 2of29 that are high in fat, protein, sugar and sodium and low in fibre, is considered to be a key driver behindthecurrentepidemicofchronicdiseases[6,7]. Incomparison, balanceddietsconsistingof moderatefatandhighinwholegraincarbohydratesareassociatedwithreducedriskofdiseaseand improvedmortality[7]. DietarytherapyhashistoricallybeenusedinthemanagementofCKDand guidelinesexistsurroundingtheintakeofproteinandsodiumforpatientswithCKD[8]. Adherence tocurrentdietaryguidelinescanreducetheincidence,orslowtheprogressionofCKDandimprove mortality[9]. Evidenceisemergingtosuggestthattherearemanyothernutrientsthatcanpotentially influencekidneyhealtheitherthroughmetabolicorhaemodynamiceffects,orviathemodificationof guthomeostasisincludingchangestogutmicrobiota. Thepurposeofthisreviewistosummarisethe keyrecommendationstodate,andtoprovideanoverviewofrecentliteraturepertainingtopotential novelmodifiabledietarycomponentsthatmaybeusefulinthetreatmentofCKD. 2. Protein DietaryproteinrestrictionhasbeenrecommendedforindividualswithCKDfordecades. Early experimentalevidenceinanumberofrodentmodelsofkidneydisease,includingmodelsofdiabetic nephropathyandspontaneouslyhypertensiverats,consistentlydemonstratedthatlowproteindiets amelioratetheprogressionofglomerulardysfunction[10,11]. Evidencethatproteinrestrictionwas beneficialinimprovingalbuminuriainpatientswithkidneydiseasewasfirstdescribedin1986[11,12]. CurrentrecommendationsforproteinintakeinindividualswithCKDstages1–4is0.8g/kgbody weight, and avoidance of high protein intake (>1.3 g/kg/day) [13]. The key benefits of protein restriction are primarily thought to arise from the amelioration of proteinuria and it has been proposed that an even lower protein intake of 0.6–0.8 g/kg bodyweight in patients with CKD stages3–5maybedesirable[11,14]. Furtherdietaryproteinreduction,usingaverylowproteindiet supplementedwithketoanaloguesofessentialaminoacids(0.35g/kg/day)hasbeenshowntoreduce bloodpressureinCKDpatients[15,16]. Otherfactorsthatoccurduetoexcessproteinmetabolism, such as increased GFR [17], metabolic acidosis [11] and oxidative stress [18], are also thought to contributetokidneydamageassociatedwithhighproteinintake[11].Despitesubstantialexperimental evidence to indicate that dietary protein restriction prevents the development of proteinuria and renal fibrosis [19–21], many clinical studies in humans have failed to find the same level of renal protection [11,22–24]. The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRM) study found that a low proteindiet(0.58gprotein/kg/day)didnotsignificantlyimproveglomerularfiltrationrateinCKD patientswhencomparedtoastandardproteindiet(1.3g/kg/day)atatwo-yearfollow-up[24]. This islikelybecauseoftheextremedifferencesinproteincontentusedinexperimentaldiets,butmayalso beduetotheeffectofotherfactorsassociatedwithproteinfoods,suchasenergy,water,sodiumand phosphorous,thatmayaffectkidneyfunction[11]. Proteinenergywastingisamajorcomplicationof kidneydisease[25],particularlyinlaterstages. Along-termfollow-upofpatientsfromtheMDRM studyfoundthatassignmenttoaverylowproteindietsupplementedwithamixtureofessentialketo acidsandaminoacids(0.28gprotein+0.28ketoandaminoacids/kg/day)wasassociatedwitha significantlygreaterriskofdeathcomparedtoalowproteindiet(0.58g/kg/day)[26]. Thoughit wasnotclearwhetherthisfindingmaybeduetothereducedmeanenergyintakethatoccurredwith theverylow-proteindiet,orthepossibletoxicityoftheketoacidsandaminoacidssupplement[26]. Consequently,effectivestrategiestoimproveGFRorreduceproteinuriawithoutjeopardisingprotein balanceareahighpriorityinadvancingCKDtreatment. 2.1. ProteinSourceandMetabolicAcidosis Growingevidencesuggeststhatthesourceofprotein(plantoranimal)maybemoreimportant thanthequantityofproteinconsumed(Figure1). Onereasonforthisisthetendencyforexcessmeat intaketodisrupttheacid-basebalance. MetabolicacidosisisacommonoccurrenceinCKDpatients andresultsinlowcirculatingbicarbonate—ariskfactorfortheprogressionofnephropathy[27,28] and is associated with increased mortality [29]. Protein from animal sources is composed of Nutrients2017,9,265 3of29 sulphur-containingaminoacidswhich,whenoxidized,generatesulphate,anon-metabolizableanion that contributes to total body acid load [30]. Protein from plant sources contains higher levels of glutamate,ananionicaminoacidthatuponmetabolismconsumeshydrogenionstoremainneutral, thereby reducing acidity levels [30]. Plant foods are also generally higher in anionic potassium salts, which also result in the consumption of hydrogen ions upon metabolism and reduction in acidload[30]. Inresponsetoanincreaseinacidloadthekidneyadaptsbyincreasingammonium Nutrients 2017, 9, 265 3 of 28 ionexcretioninordertoexpelexcesshydrogenions,thereforeincreasingthedemandforammonia anion that contributes to total body acid load [30]. Protein from plant sources contains higher levels production[30]. Thisstimulatesthebreakdownofglutamineandotheraminoacidspromotingprotein of glutamate, an anionic amino acid that upon metabolism consumes hydrogen ions to remain catabolismandmusclewasting[31]whilealsoleadingtorenalhypertrophy[32]. Metabolicacidosis neutral, thereby reducing acidity levels [30]. Plant foods are also generally higher in anionic alsoprompoottaesssipurmo tseailnts,m wuhsicchle awlsoa srteisnuglt viina tthhee caocntsiuvmaptitoionn ooff thhyedAroTgPen- dioenpse nudpoenn tmuebtaibqouliistmin -apnrdo teasome system[3r3e]d.uIcntiorne sipn oancisde lotaoda [3h0i]g. hIn arcesidpolnosae dto, tahne inkcirdeanseey ina alsciod ulonadd etrhge okeidsnfeuyn acdtaioptnsa blyc ihnacrnegaseisngin cluding promotionamomfgonloiumme riounl aerxchryetpioenr fiinl torardtieor ntoa enxdperle enxaclesvsa hsyoddriolgaetino ino,nfse, athtuerreefosrtey ipniccraealsoinfge athrley ddemiaabnedt ickidney for ammonia production [30]. This stimulates the breakdown of glutamine and other amino acids disease[30]. ResultsoftheChronicRenalInsufficiencyCohortStudysuggestthatconsumptionofa promoting protein catabolism and muscle wasting [31] while also leading to renal hypertrophy [32]. greaterproportionofproteinfromplantsourcesisassociatedwithhigherbicarbonatelevelsaswellas Metabolic acidosis also promotes protein muscle wasting via the activation of the ATP‐dependent animprovuebdiqupihtino‐spprohtoearosoumseb asylastnemce [i3n3]p. aItni ernestspownsiteh toC Ka Dhig[3h4 a].ciTdr ilaoalsd,i nthheu kmidanneys ianlsvoe sutnigdaertginoges theeffect ofplantsfouuncrtcioenpalr octheainngevse irnsculusdainngi mpraolmsootuiornc eopf rgolotemienrualraer lhiympietrefidlt,rabtiuont saondfa rresnualg gveassotdtihlaatitonin, creasing features typical of early diabetic kidney disease [30]. Results of the Chronic Renal Insufficiency theproportionofdietaryproteinfromplantfoodsimproveskidneyhealth. Alongitudinalcontrolled Cohort Study suggest that consumption of a greater proportion of protein from plant sources is trial in patients with diabetic nephropathy reported that replacing proteins from animal sources associated with higher bicarbonate levels as well as an improved phosphorous balance in patients withsoywpirtoht CeKinDi [m34p].r Torviaelsd inp hruomteainnsu inrivaesatingdatiungri tnhae reyffeccrte oaf tpilnainnt esoausrcwe perloltaeisn mvearsrukse arnsimofalc saorudrcieo vascular disease[3p5ro].teAin naoret hliemritsetdu, dbuyt isno fhaer asultghgyesat dthualt tisncfroeuasnindg tthhea tpirnoptaorkteiono fofv deigeteatrayb pleropterino tferoinm, pinladnte pendent oftotalpfroootdesi niminprtoavkees kreiddnueyc ehdeagltlho. mA elornugliaturdfiinltarl actoinotnrolrlaedte t,rirael nina plaptileanstms waitflho dwiabaentidc niemphprroopvatehdy albumin reported that replacing proteins from animal sources with soy protein improved proteinuria and clearancecomparedtoanimalprotein[36]. Arecentstudycomparedtheeffectofaverylowprotein urinary creatinine as well as markers of cardiovascular disease [35]. Another study in healthy adults vegetariandiet(0.3g/kg/day)supplementedwithketoanolougestoastandardmixed-sourcelow found that intake of vegetable protein, independent of total protein intake reduced glomerular proteindfiielttra(0ti.o6n gra/tek,g r/endaal ypl)aosmnaC flKowD apndro igmrpersosvieodn a[lb3u7m].inA ctleaanra1n8ce- mcoomnptahrefdo ltolo awni-muapl psriogtneiinfi [c3a6n].t lyfewer patientsfrAo mretchenet vsetruydylo wcomprpoatreeidn vtheeg eetfafercita nofd iae tvgerroyu plowre qpuroirteeidn revnegaeltraeripanla cdeimet e(n0t.3t hge/rkagp/dya,yo)r reached supplemented with ketoanolouges to a standard mixed‐source low protein diet (0.6 g/kg/day) on the primary end-point of >50% reduction in GFR [37]. A study in CKD patients with dual RAAS CKD progression [37]. At an 18‐month follow‐up significantly fewer patients from the very low blockade,notedthathighserumphosphatelevelsattenuatedtheantiproteinuriceffectofaverylow protein vegetarian diet group required renal replacement therapy, or reached the primary end‐point proteindioeft >w50i%th rekdeutcotaionna ilno uGgFRes [3[17]6. ]A, asntuddya nini mCKaDlp praotiteenints swoiuthr cdeusalc RoAnAtaSi nblmocokardeeb, inooatevda itlhaabt lheigphh osphate, which nosterounmly pihnocsrpehaastee sletvoetlsa labttoenduyataedc idthele avnetlisprboutetiniusriacl seoffeuctn dofe ras tvoeoryd ltoowb peroateuinr edmieitc wtoitxhi n that is associatedkewtoiatnhalaolul-gceas u[s1e6],m aonrdt aalniitmya(ld pisrcoutesins esdoubrecelos wco)n[t3ai2n] .mAorve ebriyoalvoawilapblreo tpehionspvheagtee,t awrhiaicnh dnioett hasalso only increases total body acid levels but is also understood to be a uremic toxin that is associated beennotedtoreducemetabolicacidosisinacohortofCKDpatients[38]. Fruitandvegetablesare with all‐cause mortality (discussed below) [32]. A very low protein vegetarian diet has also been sourcesofdietaryalkaliandinterventionstoincreasefruitandvegetablesinCKDpopulationshave noted to reduce metabolic acidosis in a cohort of CKD patients [38]. Fruit and vegetables are sources beenshowof nditeotariny carlkeaalsi eanpdl ainstmeraveCntOio2nsl etov einlcsre[3as9e, 4fr0u]i,t iannddi cvaegtievtaebloefs ainm CeKliDo rpaotpioulnatoiofnms heatvaeb boeleinc acidosis. Takentogsehtohwenr ,toth inecerevaisde epnlacsemsau CgOg2e lsetvseltsh [a3t9,i4n0c],r ienadsicinatgivteh oef apmroelpioorrattiioonn oof fmpeltaabnotl-ibc aacsieddospisr. oTtaekienn intakein together, the evidence suggests that increasing the proportion of plant‐based protein intake in patientswithCKDmayimproverenaloutcomes,providedthereisanadequatequantityofproteinto patients with CKD may improve renal outcomes, provided there is an adequate quantity of protein preventproteinenergywasting. to prevent protein energy wasting. Figure 1. Mechanisms of dietary factors impact on chronic kidney disease. n‐3 PUFAs = Omega 3 Figure1. Mechanismsofdietaryfactorsimpactonchronickidneydisease. n-3PUFAs=Omega3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. CRP = C‐Reactive Protein. MCP‐1 = Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein‐1. PolyunsaturatedFattyAcids.CRP=C-ReactiveProtein.MCP-1=MonocyteChemoattractantProtein-1. Nutrients2017,9,265 4of29 2.2. ProteinFermentationbytheColonicMicrobiota Themicrobialmetabolismofproteinalsoproducesanumberofmetabolitesthatmaynegatively affect the kidneys. The fermentation of protein in the colon results in the production of indoxyl sulphate and p-cresylsulphate (the conjugated form of p-cresol), which are known nephrotoxic compounds [41]. Circulating indoxyl sulphate can increase oxidative stress in the renal tubular cellsandtheglomeruli[42].Also,invitroindoxylsulphatehasbeenobservedtoactivateinflammatory pathwaysresultinginanincreaseintheexpressionofmonocytechemoattractantprotein-1(MCP-1)and intracellularadhesionmolecule-1(ICAM-1)[43]. P-cresylsulphatehassimilarlybeenlinkedtoCKD andCVDmortality,althoughthemechanismisnotaswelldefined[44,45]. Interestingly,ithasbeen notedthatvegetarianshavelowerlevelsofthesenephrotoxiccompoundscomparedwithomnivores, in bothhealthy [46] andCKDpopulations [47]. Vegetarians tendto havehigher fibre intakes[46], whichcouldbemetabolizedbythecolonicmicrobiotainsteadofaminoacids,leadingtoareductionin indoxylsulphateandp-cresylsulphate. Thisprovidesanothermechanismtoexplainwhyvegetarian protein sources appear less detrimental than animal protein sources. Furthermore, carnitine and lecithinpresentinredmeataremetabolizedbythemicrobiotatoformtrimethylamine-N-oxide[48], whichhasbeenlinkedtocardiovascularevents. Theinteractionbetweenanimalsourcesofproteinand gutbacteriainCKDwarrantsfurtherinvestigation. Determininganoptimumproteintofibreratio couldallowforappropriateproteinintaketopreventproteinenergywasting,withoutadverseeffects onrenaloutcomes. 3. DietaryFibre/NonDigestibleCarbohydrates Dietaryfibrewasconsideredasatreatmentforchronicrenalfailuremorethan30yearsago,where itwasfoundtoreduceplasmaurea[49]. Sincethen,interesthasextendedtoavarietyofnon-digestible carbohydratesfortheirabilitiestoimpactmarkersofCKD.Non-digestiblecarbohydratesareresistant tohydrolysisbyhumandigestiveenzymes,areabletopassthroughthegastrointestinaltractintothe largeintestineandincludedietaryfibres,non-starchpolysaccharides,β-linkedoligosaccharidesand resistantstarch[13]. HumanStudies—Intervention Chronickidneydiseaseresultsinastateofchroniclow-gradeinflammation,withincreasesseenin pro-inflammatorymarkerssuchasinterleukin6(IL-6)andC-reactiveprotein(CRP),whichcontributes toworsenedmortalityoutcomesinthispopulation[50]. Epidemiologicalsurveydataindicatedan inverse association between dietary fibre intake and the inflammatory marker CRP and mortality inpatientswithCKD[51]. Suchepidemiologicaldatashouldbeinterpretedwithcaution,however, asthereissomeuncertaintyaboutwhetherdietaryfibreperseisbeneficialorwhetherothernutrients, includingantioxidantcompoundsthatarepresentinfibre-richfoods,actinabeneficialmanner[52]. Interventionsthathavefocusedonincreasingtotaldietaryfibreintakeinpatientswithpre-dialysis CKDhavereportedreductionsinserumcreatininelevels[53]andplasmap-cresol[54]. Afour-week studyinwhichpatientswithchronicrenalfailureconsumed50gramsperdayofacaciagum,ahighly fermentablefibre,ledtoameanreductioninplasmaureaof12%[55]. Supplementationwithacacia gum for three months led to decreases in serum urea, creatinine and phosphate by 31%, 10% and 22%,respectively[56]. Arecentmeta-analysisofhumantrialsfoundthatdietarysupplementation with fermentable fibres was associated with a reduction in serum urea and creatinine in patients with stage 3–5 CKD (pre-dialysis only); however, it should be noted that most of the trials (86%) thatwerereviewedwereconsideredtobeofalowquality[57]. Recently,severalshorttermstudies havebeenundertakenusingnondigestiblecarbohydratesinpatientsreceivingdialysis. Afour-week Belgian study in haemodialysis patients showed that plasma p-cresylsulphate decreased by 20% whensupplementedwitholigofructose-enrichedinulin[58]. Thisresulthasbeenechoedinasimilar studythatcombinedgalacto-oligosaccharideswithprobiotics[59]. Whilstneitherofthesestudies Nutrients2017,9,265 5of29 showedareductioninindoxylsulphate,arecentsix-weekdietaryinterventionwithresistantstarchin haemodialysispatientsledtoameanreductionofplasmaindoxylsulphateandp-cresylsulfateby29% and28%,respectively[60]. Whilstthesestudiesshowanimprovementinthelevelsofuremictoxins, thishasyettobetranslatedintohardclinicaloutcomessuchasCVDeventsandmortality. Current Australian guidelines recommend that patients with early CKD consume a diet rich indietaryfibre; however,thisrecommendationwasgiventhelowestevidencegradingscore(2D), indicating that this is a weak recommendation based upon very low-quality evidence [61]. Other guidelinesforthemanagementofCKDmakenomentiontotheroleofnon-digestiblecarbohydrates[8], whichsomecommentatorsfeelshouldberectifiedonthebasisofemergingevidence[52]. Dietary fibreintakeisabout20%–30%lowerinhaemodialysispatientscomparedtocontrolsubjects[62,63], withdialysispatientsconsumingapproximately11(±6)g/daydietaryfibre,significantlylessthanthe recommendationof25g/day[64]. Thesedatasuggestthatnon-digestiblecarbohydratesareeffective atimprovingbiochemistrymarkersinhaemodialysispatients,andthatdietaryinterventionsinvolving thesecompoundsmaybeparticularlyrelevantgiventhelowintakesseeninthispopulation. Theuseofnon-digestiblecarbohydratesforthetreatmentofCKDisanemergingfieldandithas beennotedthatthereisapaucityofstudiesrelatedtoclinicaloutcomes[65]. Theuseofdietaryfibre supplementationisasimple,non-invasiveoptionthatdoesnotnegativelyimpactpatients’qualityof life[66],althoughsomeprebioticcompoundshavebeennotedtohaveminornegativegastrointestinal effectswhenconsumedathighdoses[67]. 4. Sodium High dietary sodium intake is a risk factor for hypertension, which is understood to be both a cause and a consequence of CKD [68]. Hypertension promotes glomerular hyper-filtration and proteinuriaandthereforeincreasestherateofprogressionofCKD[8,69]. Highbloodpressurecan leadtovascularremodellinginthekidney,whichisthoughttobethecauseofsubsequenttubular atrophy, glomerulosclerosis and reduced filtration surface area [69]. These structural changes in the kidney, whether they initially occur due to hypertension or by other factors such as diabetes, impair the excretion of sodium [70]. Therefore, high dietary sodium intake in CKD can worsen existing hypertension, or result in the development of salt-sensitive hypertension [68]. Current guidelinesforsodiumintakeforindividualswithCKDstages1–4arelessthan2000mgperday[13]. Theserecommendationsarebasedontheresultsofalargesystematicreviewofexperimentaland non-experimental studies, which, despite varying quality and heterogeneity of included studies, consistently show that high sodium intake is associated with kidney tissue injury and worsening albuminuria [71]. Salt restriction in patients with moderate to severe CKD has been shown to significantlyreducebloodpressure,albuminuriaandproteinuria[72]. Thedegreeofimprovement inthesemarkerswassignificantlygreaterinpatientswithCKDthanwithout,supportingtheidea thatpatientswithCKDareparticularlysalt-sensitive[72]. Interestingly,restrictingdietarysodium intakeinpatientswithCKDonangiotensinconvertingenzyme(ACE)inhibitorswasmoreeffective thandualblockadeoftherenin-angiotensin-aldosteronesystem(ACEinhibitorplusanaldosterone receptor blockade) in reducing blood pressure and proteinuria [73]. This trial, although possibly underpoweredforabloodpressurestudy,highlightstheimportanceofCKDpatientsaccomplishing sodiumrestrictionwhilebeingtreatedwithACEinhibitorstobestimproverenalmarkers. 5. Potassium In addition to the direct benefits of reducing dietary sodium intake on blood pressure and proteinuria,reducingconsumptionofhighsodiumfoodsgenerallyincreasestheamountofpotassium inthediet[74].Potassiumisunderstoodtobeantihypertensiveandmayabolishsodiumsensitivity[74]. An improved sodium to potassium ratio may be one reason why the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension(DASH)diet,whichcontainstwicethepotassiumofastandardwesterndiet,iseffective inreducingbloodpressure[74]. TheDASHdiethasnotbeenwidelyassessedinpatientswithCKD Nutrients2017,9,265 6of29 duetothehighprotein,potassium,calciumandphosphorouscontent[75]. Inpatientswithsevere CKD, such as those on dialysis, impaired potassium excretion leads to hyperkalaemia, which is associated with higher all-cause mortality [76]. For this reason intake of potassium is restricted in these patients. However, during earlier stages of CKD a diet high in potassium, such as a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, may slow progression to later stages through lowering blood pressure[74]. AsmallretrospectivestudyfoundthattheDASHdietwasstilleffectiveinindividuals withreducedkidneyfunctionatbaseline[75]. LargerstudiesarerequiredbeforetheDASHdietcanbe recommendedtoCKDpatients. However,itislikelythatthebenefitsofplant-baseddietsnaturally highinpotassiumandfibreandlowinacidogenicproteinsandmineralswouldoutweighthepotential riskofdevelopinghyperkalaemiainearlyCKD.Inagroupofstage4CKDpatients,selectedtobeat lowriskforhyperkalaemia,treatingmetabolicacidosiswithbase-producingvegetableswaseffective in improving metabolic acidosis and reducing kidney injury [40]. Larger long-term trials in CKD patientsinvestigatingplant-baseddietsonrenalbiomarkersandclinicaloutcomesarewarrantedon thebasisofthepositivefindingstodate. 6. VitaminD The kidneys play an important role in the metabolism of vitamin D into its active form, from vitamin D precursors which are obtained either through the diet or from conversion of 7-dehydrocholesterolintheskinbyUVlight. Theseprecursorsareconvertedinthelivertocalcidiol (25 hydroxy vitamin D), which is further converted into the active form of vitamin D, calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitaminD3)inthemitochondriaoftheproximalconvolutedtubulesofthekidney, byanenzymecalledrenal1-αhydroxylase. Askidneyfunctiondeclinesthereisadirectdecrease in the synthesis of calcitriol [77]. Calcitriol suppresses the release of parathyroid hormone (PTH); however, in CKD this mechanism is blunted due to decreased production of calcitriol, leading to over-release of parathyroid hormone in a condition called secondary hyperparathyroidism. This secondary hyperparathyroidism can lead to alterations in bone turnover and metabolism and the developmentofrenalosteodystrophy[78]. VitaminDdeficiencyandsecondaryhyperparathyroidism arerecognisedtobecomplicationsassociatedwithchronickidneydisease[61]. 6.1. LowVitaminD,CKDandAssociationwithMortality Cardiovascular disease is a significant contributor to mortality in patients with renal disease, withsuddencardiacdeathaccountingfor20%–30%ofdeathsindialysispatients[79]. Haemodialysis patientswithaseverevitaminDdeficiency(≤25nmol/Lof25(OH)D)haveathreefoldhigherrisk of sudden cardiac death compared with those with vitamin D levels greater than 75 nmol/L [80]. A meta-analysis of data from observational studies showed that, for each 25 nmol/L increase in serumlevelsof25(OH)Dtherewasasignificantdecreaseintherelativerisk(RR=0.86,CI:0.81–0.92) of mortality [81]. Altered vitamin D levels and subsequent hyperparathyroidism can contribute to the formation of extracellular insoluble calcium phosphate and subsequent calcification of the vasculature[78].CoronaryarterycalcificationhasbeenreportedinpatientswithCKD[82],andcalcium phosphatelevelshavebeenshowntocorrelatewithincreasedmortalityriskinHDpatients[83]. Low plasma25(OH)Disalsoassociatedwithahigherriskofdevelopingincreasedalbuminuria,particularly inindividualswithhighsodiumintake[84]. ThusitisthoughtthatcorrectingvitaminDlevelsmay reducePTHlevels,correctalterationsinboneturnoverandcalciummetabolism,andsubsequently reducemortalityintheCKDpopulation. 6.2. VitaminDSupplementationandParathyroidHormone NewervitaminDanalogues,suchasparicalcitol,playanimportantroleinCKDastheyappearto havebettersuppressionofparathyroidhormoneandpossiblylessofacalcaemiceffectcomparedto othervitaminDsterolforms[85]. Severalstudieshaveshownthatparicalcitolsupplementationin CKDpatientswasassociatedwithadecreaseinPTHlevels[86–88]. ThestudybyAlborzietal. did Nutrients2017,9,265 7of29 notfindanychangeinPTHlevels,whichmaybeduetoitsshorterdurationofonemonth[89]. Data frombothobservationalstudiesandRCTsshowedthatvitaminDsupplementationimproveslevels ofparathyroidhormoneinbothpre-dialysisanddialysis-requiringpatients[90]. Whilstitmaybe effectiveinloweringparathyroidhormonelevels,someconcernhasbeenraisedoverthepotentialrisk thatparicalcitolmayexacerbatevascularcalcification[91]. 6.3. VitaminDSupplementationandProteinuria Reduction of residual proteinuria is associated with reductions in serum creatinine levels, progression to end-stage renal disease and mortality [92]. Several studies have shown that oral supplementationwiththevitaminDanalogparicalcitoliseffectiveatreducingproteinuriainstage 2–4 CKD patients [87–89,93]. Furthermore, oral paricalcitol therapy achieves these reductions in proteinuria without an increase in adverse events [77]. A meta-analysis of trials in CKD patients showedthatsupplementationwithvitaminDwasassociatedwithameanreductioninproteinuriaof 16%,whichwasareductionseeninadditiontotheeffectseenbyRASblockade[94]. WhilstvitaminD supplementationdoesreduceproteinuria,thisisnotassociatedwithchangesinothermarkersofrenal functions,suchasGFR,anddoesnotappeartoaltertheriskofpre-dialysisCKDpatientsprogressing todialysis[85,91]. Thislackofaneffectonclinicaloutcomesisperplexing,astrialsthathaveused RASblockerstoreduceproteinuriatoasimilarextentwereassociatedwithimprovementsinGFRand reducedprogressiontoESRD[92,95,96]. Apossibleexplanationmaybeinsufficientstudyduration; inthemeta-analysisbyXuetal. 12studiesassessedvitaminDsupplementationandGFR,ofwhich sevenhadaninterventionthatlastedforsixmonthsorless;threestudiesranfor12months,whilstthe remainingstudieshaddurationsof18and24months,respectively. 6.4. VitaminDSupplementationandClinicalOutcomes—Mortality WhilstvitaminDsupplementationhasbeenshowntoalterbiochemicalparametersofpatients with CKD, the effect on morbidity and mortality outcomes in this patient group is less clear. A meta-analysis of observational studies showed that patients with CKD receiving vitamin D supplementation had a reduction in risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality [97]. However,arecentmeta-analysisthatlookedspecificallyatRCTsthatassessedtheeffectofvitaminD supplementationonall-causeandcardiovascularmortalityinCKDpatientsfoundnoevidencethat supplementationaffectedmortalityoutcomes[98]. Ofthepatientsinthismeta-analysis,abouttwo thirdswerefollowedupforlessthanayear,andithasbeensuggestedthatthismaybeinsufficient follow-up time to capture CVD events, which are a major contributor to mortality in the CKD population[99]. ManystudiesassessingtheefficacyofvitaminDinCKDpatientsutilisebiochemicaloutcomes, suchasparathyroidlevelsorproteinuria,ratherthanclinicalendpointssuchasprogressiontoESRD ormortality[77]. Arecentumbrellareviewfoundthattherewasalackofconvincingevidencefor vitaminDsupplementationacrossarangeofhealthoutcomes,includingchronickidneydisease[100]. CurrentAustralianguidelinesrecommendvitaminDsupplementationinthosewithearlychronic kidneydiseaseandsecondaryhyperparathyroidismthoughadmitsevidencedoesnotexisttosupport thatthisleadstoimprovementinpatient-leveloutcomes[61]. ThuswhilstvitaminDmayeffectively alterbiochemicalparameters, larger, longerrandomisedcontroltrialsareurgentlyrequiredtosee whetherthesetranslateintomeaningfulpatient-centredoutcomes. 7. Phosphorus The kidneys play a major role in phosphorus homeostasis with the glomeruli filtering between3700and6100mgofphosphorusperday,although75%–85%ofthisisreabsorbed,primarily throughtheproximaltubules,resultinginnetexcretionofbetween600and1500mgofphosphorus perday[101]. Askidneyfunctiondeclines,thereisadecreaseinthenumberoffunctioningnephrons and subsequent decrease in phosphorus excretion [102]. As renal function decreases to less than Nutrients2017,9,265 8of29 80% of normal, phosphorus absorption can exceed the rate of clearance by the kidneys, and a subsequent rise in serum phosphate levels is seen [61,103]. Phosphate anions can combine with extracellular cationic calcium to form insoluble calcium phosphate and subsequent calcification can occur, particularly in the cardiovascular system [78]. Hyperphosphataemia is associated with vascular calcification [104], increased cardiovascular disease risk [105] and increased mortality in both predialytic CKD patients [106–108] and patients receiving dialysis [109–111]. Furthermore severalstudieshaveshownthatelevatedphosphatelevelsareassociatedwithafasterrateofrenal diseaseprogressioninCKDpatients[112–115]andhealthysubjectswithnormalrenalfunction[116]. Maintainingnormalphosphatelevelsorminimizinghyperphosphataemiaisseenasacrucialstepto limitmortalityinCKDpatients. 7.1. DietarySourcesofOrganicPhosphorus Phosphorousmaybepresentinthedietasorganicorinorganicphosphate. Protein-richfoods suchaslegumes,meat,poultry,fish,eggsanddairyproductsarethemainsourcesoforganicphosphate andthereisacorrelationbetweendietaryintakesofproteinandphosphorous[117];however,ahigh protein(andhighphosphorus)dietdoesnotalwaystranslatetoincreasedserumphosphatelevels[118]. The bioavailability of organic phosphate varies depending on the food source with plant sources havingalimitedbioavailabilityduetothephosphorousbeingpresentlargelyasphytate. Humans (andothermonogastricanimals)lacktheenzymephytaseandthuscannotdigestphytate,although somedegradationmayoccurviatheintestinalmicrobiota[119]. Dairyproductshaveabout30%–60% bioavailability,andthehighestbioavailabilityoforganicphosphate,inmeatproducts,maybeashigh as80%[102]. Thisdifferenceinphosphorusbioavailabilitybetweenmeatandplantproteinsources, maypartiallyexplainthebenefitsofconsumingagreaterproportionofproteinfromplantssources, asdescribedabove. Phosphateabsorptionislinearlyrelatedtophosphateintake,withbioavailability being the major determining factor in phosphate uptake from the diet [120]. Thus, for organic phosphate,foodchoicescanmakeasignificantdifferenceintheamountofphosphatethatisabsorbed fromthediet. 7.2. DietarySourcesofInorganicPhosphorous Phosphorous may be added to foods in the form of inorganic additives, which are typically used to improve taste, texture, shelf life or processing time [121]. These additives are primarily inorganic phosphate salts that require no enzymatic digestion and dissociate rapidly in the low pHenvironmentofthestomach;thusinorganicphosphateadditiveshaveahighbioavailabilityof 90%–100%[102]. Phosphoricacid,whichispresentincoladrinks,hasabioavailabilityof100%[121]. Inorganic phosphate additives are found in many processed foods including frozen meals, snack bars,Frenchfries,spreadablecheeses,instantfoodproductsandbeveragessuchassodas,flavoured water,juicesandsportdrinks[122]. ThephosphorouscontentinatypicalWesterndiethasincreased substantiallyduringthepastfewdecades[123]andinmanycountriesdietaryphosphorusexceedsthe recommendeddailyallowance[124]. ArecentAustralianstudyfoundthatphosphateadditiveswere presentin44%ofthemostcommonlypurchasedgroceryfoods,andwereparticularlyprevalentin smallgoods(96%),bakeryproducts(93%)andfrozenmeals(75%)[125]. Inorganicphosphateisreadily absorbedandhasbecomehighlyprevalentinthefoodsupplyduetotheriseofconveniencefoodsand beverages,andisasignificantcontributortodietaryphosphateloadinatypicalWesterndiet. 7.3. ReducingDietaryPhosphorusandSerumPhosphateLevels Given the deleterious effects of hyperphosphataemia and the rising phosphate content of foods, several studies have addressed reducing dietary phosphorus to reduce serum phosphate levels. Onesmallstudyfoundthatreplacingnaturalproteinsourceswithalowphosphorusprotein concentratecanreduceserumlevelsofphosphateandparathyroidhormone[126]. Arandomised controlled trial using dietary education to limit intake of foods containing phosphate additives Nutrients2017,9,265 9of29 led to a reduction in serum phosphate levels of 0.6 mg/dL (95% CI: 0.1–1.0 mg/dL), a decrease that, the authors state, corresponds with a 5%–15% reduction in relative mortality risk, based on findingsfromobservationalstudies[127]. Dietaryreductionofphosphatecanreduceserumlevels; however, whether this translates to clinical benefits is not clear as limitation of dietary phosphate mayexcessivelylimitothernutrients—particularlyprotein,whichoftencorrelateswithphosphorous intake. Alargeretrospectivecohortstudythatconsidered30,000haemodialysispatientsfoundthat therelationshipbetweenserumphosphatelevelsandmortalityisaJ-shapedcurveandthatthose patients who had high phosphate levels and high protein intake had lower mortality compared to those patients with high phosphate levels and low protein intake [128]. Dialysis patients on a phosphate-restricted diet have greater mortality than those without phosphate restriction [129], and it has been suggested that excessive phosphate restriction may be associated with decreased dietaryproteinintakeandsubsequentproteinenergymalnutrition,whichleadstoincreasedriskof mortality[130]. Theconclusionbornfromthesestudiesisthathaemodialysispatientsshouldaimto minimizephosphorousintakewhilstnotcompromisingtheadequacyofproteinintake. 7.4. PhosphatetoProteinRatio Thishasledtorecommendationsforusingaratiobetweenthephosphatecontentandprotein content to identify foods that will provide adequate protein whilst properly controlling dietary phosphate[122]. Anobservationalprospectivefiveyearstudyfoundthathaemodialysispatientswith higherdietaryphosphate:proteinratiohadincreasedmortality,evenafterserumphosphatelevels werecontrolledfor[117]. Eggwhitehasoneofthelowestphosphate:proteinratios[102]whilstmany processed foods and beverages are high in phosphate with low protein. One study compared the phosphate:proteinratioinmeatproductspreparedwithandwithoutphosphateadditivesfoundthat therewasa60%increaseinthephosphate:proteinratiointhoseproductscontainingadditives[131]. Previousstudieshaveshownthatphosphateadditivestomeatandpoultryproductscanleadtoa nearlydoublingofthephosphorouscontentoftheseproducts[132]. Worryinglywhethermeatshave beenenhancedwithinorganicphosphateadditives,ortowhatlevel,maynotbeeasilydetermined fromthenutritioninformationpanel. WhilstmanystudieshaveshownanassociationbetweenserumphosphatelevelsandriskofCVD deathinCKDpatients,ithasbeennotedthatthereisadearthofrandomisedcontrolledtrialswith aninterventionthatmodifiesdietaryphosphateandassessesmortalityasanoutcome[123]. Whilst thisevidencemaybelackingformortalityoutcomes,thecurrentguidelinesrecommendmaintaining serumphosphatewithinanormalrangeforCKDstages3–5anddialysispatients,bydietaryrestriction andtheuseofphosphatebinders[14],withinsufficientevidenceforrecommendingdietaryphosphate restrictionforearlyCKDpatients(stages1–3)[61]. Thecurrentevidencesuggeststhatlimitingfoods that have a high phosphate:protein ratio (such as spreadable cheeses and egg yolk) and avoiding inorganic phosphate additives (such as those in cola) may improve outcomes for CKD patients. Treatinghyperphosphataemiabylimitingtheintakeofprotein-richfoodsmaycontributetomortality inCKDpatients. 8. Omega-3PolyunsaturatedFattyAcids(n-3PUFAs) In the general population fish intake is associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality, whichhasbeenattributedtothehighcontentofn-3polyunsaturatedfattyacids(n-3PUFAs)[133]. The anti-inflammatory, anti-hyperlipidaemic and antihypertensive effects of n-3 PUFAs are well established in the general population [134]; however, there is less conclusive evidence for those patientswithCKD.Inparticular,thereisadearthofconclusivestudieswithinCKDpopulationswith regardstomortality[135,136]. Nutrients2017,9,265 10of29 8.1. n-3PUFAsandTriglycerideLevels Lipid abnormalities may be a common contributing factor to cardiovascular mortality in end-stage renal disease, with elevated triglyceride levels being the major lipid alteration [136]. A 2009 meta-analysis of trials in hyperlipidaemic patients without renal impairment showed that n-3 PUFA supplementation has a clinically significant dose-dependent reduction of triglycerides levels [137]. In CKD patients, several studies have found an 8–12-week intervention with daily eicosapentaenoicacid(EPA)anddocosahexaenoicacid(DHA)supplementationresultedindecreases in triglycerides [138–145]. Furthermore several studies have shown that these interventions can improveHDLlevels[139,140,146,147]. Theevidencefromthesetrialssuggeststhatdailyn-3PUFA supplementationiseffectiveatamelioratingdyslipidaemiainCKDpatients. However,notallstudieshaveconfirmedthiseffect. Afour-weekcrossoverstudywherepatients received960mg/dayEPAand620mg/dayDHAfoundnoeffectonserumcholesterolortriglyceride levels[148]. Donnellyetal. conductedafour-weekcrossoverstudywith3.6g/dayn-3PUFAandsaw anon-significantdecreaseintriglycerides,thoughtherewasnowashoutperiodbetweentreatments, whichmayhaveledtoacarryovereffectthatmayhavemaskedtheresultinthegroupthatreceived thetreatmentbeforeplacebo[149]. Athree-monthstudyfoundthatsupplementationwith4g/day fishoiltendedtodecreaseserumtriglycerides;however,thisfailedtoachievestatisticalsignificance (p=0.07)[150]. Longerstudieshavecastadditionaldoubtontheefficacyofn-3PUFAstoameliorate dyslipidaemiainCKDpatients, withasix-monthstudyindialysispatientsreceiving960mg/day EPAand600mg/dayDHAhavingnoeffectontriglyceridelevels, althoughthisstudydidseean increaseinbothHDLandLDLlevels[151]. Severalotherinterventionstudieswith2–4g/dayfish oilhavefailedtoseeanychangesinlipidlevelsaftertwomonths[152,153],sixmonths[154,155]or 12months[156]oftreatment. Thislackofaneffect,particularlyintrialsoflongerduration,hascast somedoubtontheefficacyofn-3PUFAsinreducinghyperlipidaemia. The variation in results observed in intervention studies may result from the small sample sizes,shortdurationsanddifferencesinn-3PUFAdosingregimes[157]. Inarecentmeta-analysis, subgroup analysis found that the TG lowering effect was greater in patients with higher baseline TGlevels[158],whichmayaccountforthevariationseeninresultsfromthesesmallertrials. Inthe trialbyTazikietal. thatfoundreductioninLDLcholesterolandincreaseinHDLcholesterolafter a12-weekinterventionwith2g/dayn-3PUFAs,oneoftheinclusioncriteriawashyperlipidaemia with no current lipid lowering medications [147]. Thus positive results are more likely to be seen instudieswithpatientswhohadgreaterdegreesofhyperlipidaemiaatbaseline. Theabsorptionof n-3PUFAsmaybeincreasedupto3-foldbetweenbeingtakenconcomitantlywithahighfatmeal comparedwithalowfatmeal[159]andtimingofdosingandconcomitantfoodintakemayaffect absorptionandsubsequenteffectoftheintervention. Themajorityofstudiesinstructedpatientsto consumetheirregulardiet,andithasbeennotedthattheincreasingprevalenceoffunctionalfoods fortifiedwithn-3PUFAsmaydilutetheeffectoftheseinterventiontrials[160]. Promisingly,arecent meta-analysis that did subgroup analysis that looked at doses of less than 2 g per day found that thismorephysiologicallyrelevantdosingwasabletosignificantlydecreaseTGandincreaseHDL levels[161]. A2016meta-analysisconfirmedthatn-3PUFAsareabletolowerTGlevelsinHDpatients; however,noeffectwasseenontotalcholesterolorLDLcholesterollevels[162]. Takentogether,the evidencesuggeststhatdailyn-3PUFAsupplementationiseffectiveatreducingtriglyceridelevelsin CKDpatientswithhyperlipidaemia. 8.2. n-3PUFAsandBloodPressure CKDleadstothedevelopmentofhypertension,whichitselfcancontributetotheprogression of CKD [163], and thus interventions that reduce blood pressure in CKD patients are required. In the context of CKD, several studies have found that an eight-week intervention with 1840 mg EPA and 1520 mg DHA per day resulted in decreases in blood pressure in patients with CKD stages3–4[138]. IncontrasttothestudybyMorietal.[138],severalstudiesofsimilardurationand

Description: